I have always loved the show on television called MythBusters. They take some myth and devise some test and try it out to decide if it is a myth or fact. There are a lot of myths (or facts) out there about water in the state of Idaho. So let’s see if we can put some of them to the test.

Myth or fact: One man’s irrigation wastewater is another man’s water right

So what would the test be? Let’s look at history. When they started irrigating in the early days, they dug canals that would divert from the river and wind out through some farmground, and eventually the end would loop back to the river or stream. They flood irrigated and the runoff would end up back in the canal and eventually back in the river or stream. If the farmer took a couple of days off, his water would just go down the canal and back into the river. The same thing happened in small streams; whatever they didn’t use went on down the stream and become someone else’s water.

Of course, there were some canals that lost a lot of their water to the aquifer. They ran over gravel beds or lava beds and lost a good portion of their water. This water seeped into the aquifer. Some of them lost 50% or more to the aquifer. Is this water lost or does it become water for somebody else?

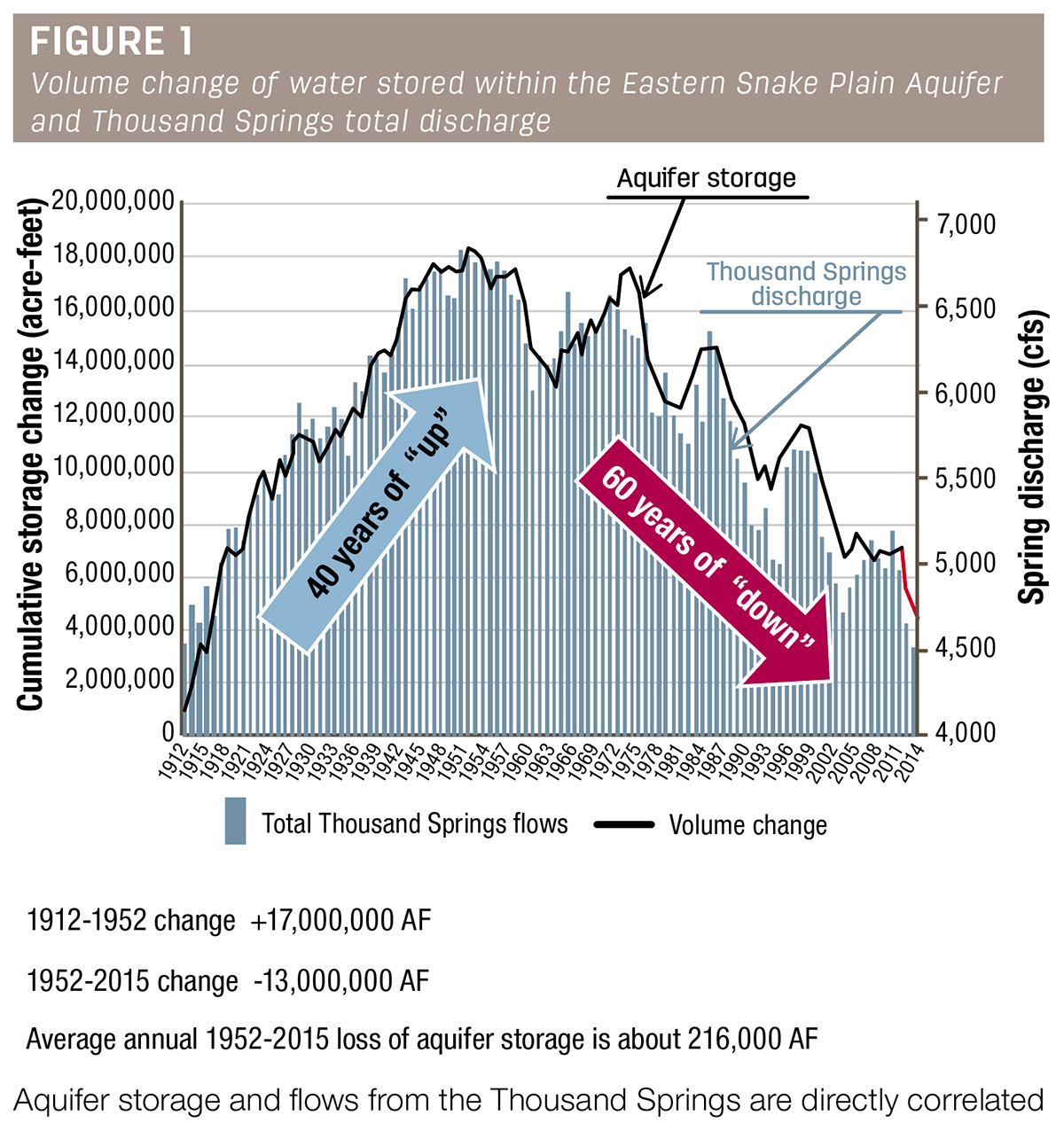

Over the years, people dug domestic wells, along with towns and neighbors. That became their water. From 1900 to 1950, the Snake Plain Aquifer benefited tremendously (Figure 1).

- Pre-1950s canal, 40% to 50% efficient

- Lined leaky sections

- Groundwater pumping

- Palisades winter run

- Surface (40% to 50%) to sprinkler irrigation (60% to 80%)

- With sprinklers, more irrigated acres

They ran the canals year-round to provide water to the ranches and farms during the winter.

The first deep irrigation wells started in the mid-1940s and have increased ever since.

Along with the deep irrigation wells, "winter water savings" started with the construction of the Palisade Reservoir. To fill Palisade Reservoir, the canals shut off during the winter and that water was stored in Palisade. Irrigators were given storage water in Palisade to compensate them for the winter water. That started in the late 1950s.

Also, sprinkler irrigation started taking over and is now widely used. This took place not only on the Snake River Plain, but in all the tributary streams and rivers. That is the way the West was settled.

I think it is safe to say that it is a fact that “one man’s irrigation wastewater is another man’s water right.” Thank goodness for old leaky canals.

Myth or fact: The Snake River is a two-river system

Is that a fact or myth? Let’s look at the Snake River right now. We are filling all the reservoirs in the Upper Snake River and doing some recharge out of Milner Dam with the water that is left over below Minidoka Dam. There is zero flow going below Milner Dam, so how does the Snake River look full at Glenns Ferry?

Because of Thousand Springs, it is replenished and starts again. Helping us reach the winter flow requirement at Swan Falls. This water then goes on down, providing a great deal of the power we use in the state of Idaho.

Nearly every year now, that is the way the system is operated. What an unbelievable river we have. I would say the Snake River is a two-river system. It starts in the mountains, ends at Milner and is reborn in the Thousand Springs area.

It is a working river that we need to take care of. Water conservation is what everybody is clamoring for – to become more efficient, line the canals, pipe the laterals, automate the irrigation projects. We’ve got to become more efficient.

Just remember, all this water conservation will have consequences. It could be your water right that is affected. Let’s make sure we get the right consequences for everybody involved.