Fertilizer prices have been on a dramatic run since the end of 2020. Global urea prices increased by more than 130% from January to October 2021. In November 2021, the retail prices for DAP and potash in the U.S. were either almost double or more than double the levels from a year ago. Such unprecedented price increases across all types of fertilizers are causing concerns among agricultural producers throughout the world, including in Idaho, regarding the profitability implications for the 2021-22 crop year.

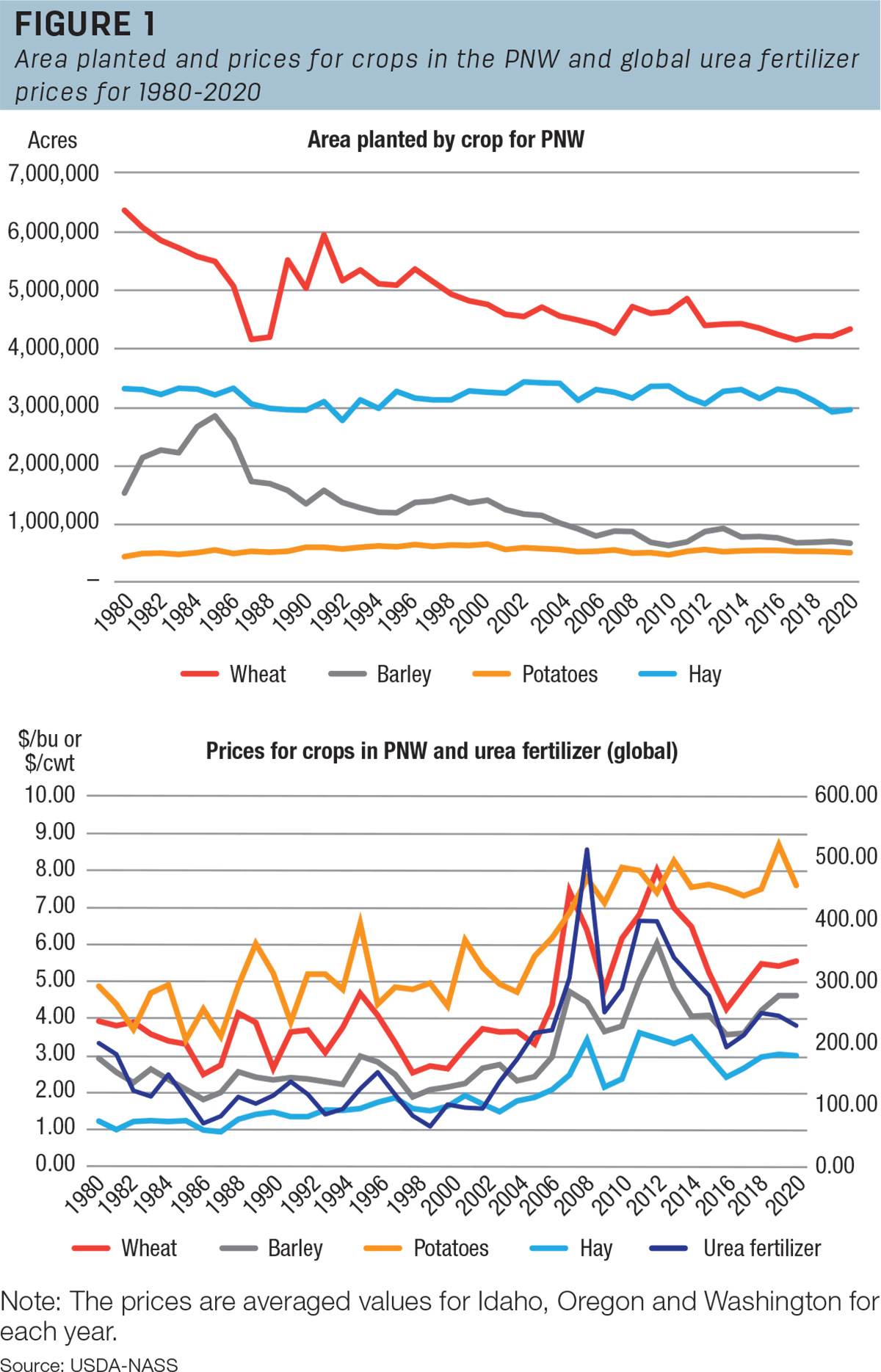

The relative profitability of crops, which considers the expected crop sales prices, yields and total operating costs, could impact producers’ planting decisions. The historical data (Figure 1) show that fertilizer and crop prices have fluctuated over time.

The abnormally steep rates of fertilizer price increases over the final months of 2021, however, may cause producers to pore over their budget numbers a bit closer in the 2021-22 crop year. This article describes how planted area and prices for key crops (alfalfa hay, barley, potatoes and wheat) in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) have varied since 1980, and examines some of the key factors that have influenced planted area variation in the PNW over the past four decades.

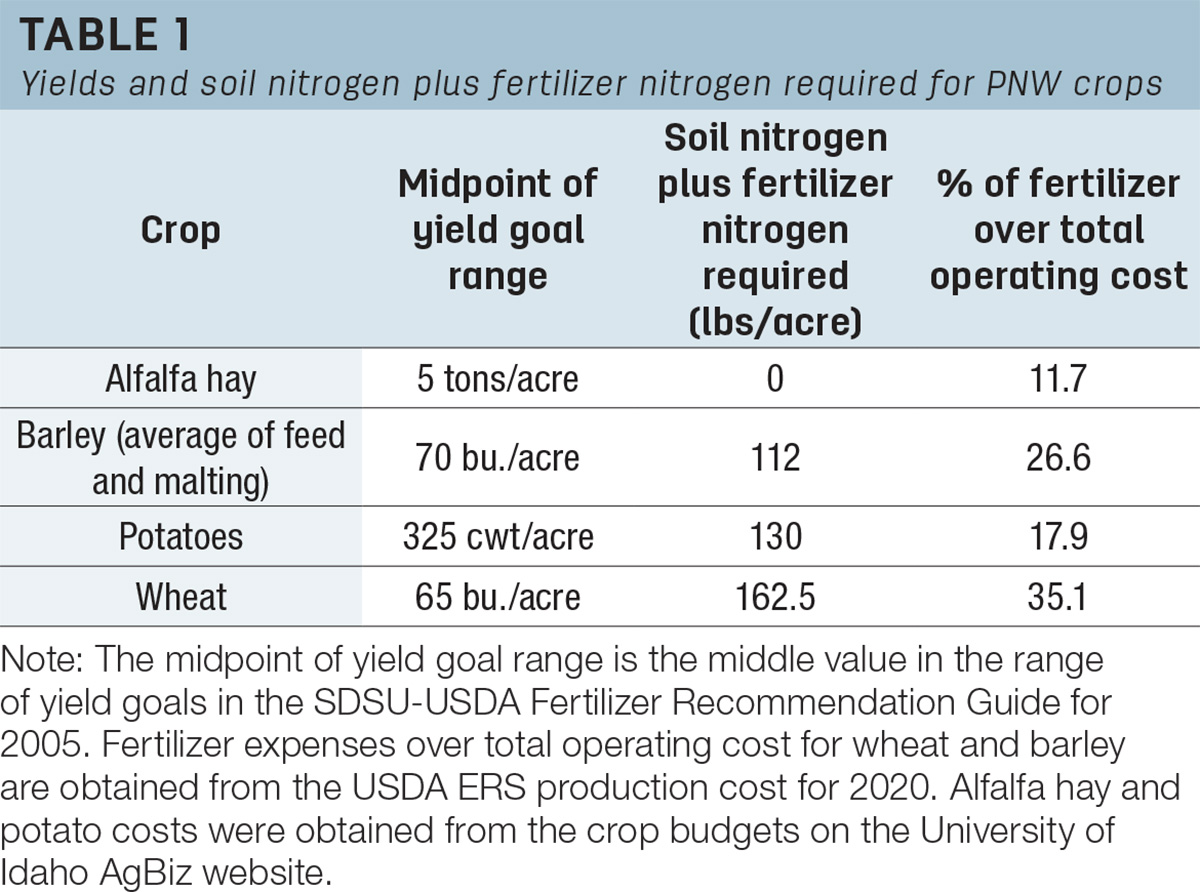

While it is expected that prices of a given crop (hereafter referred to as “own prices”) influence planted area decisions for all crops, whether fertilizer prices also matter and the extent to which they do remains an empirical question. Key to the consideration is the fertilizer requirements for each crop. Table 1 displays the soil nitrogen (N) plus fertilizer N required, as listed in the South Dakota State University and USDA “Fertilizer Recommendations Guide” from 2005, and percentage of fertilizer cost over total operating cost using data from the USDA Economic Research Service (ERS) and the University of Idaho Extension for alfalfa hay, barley, potatoes and wheat.

At the midpoint of the yield goal range, alfalfa hay requires zero N fertilizer, while wheat requires the most N at 162.5 pounds per acre. Barley (112 pounds per acre) requires slightly less N than potatoes (130 pounds per acre). In 2020, fertilizer expenses accounted for 26.6% and 35.1% of the total operating cost for barley and wheat production in the U.S., respectively. For alfalfa hay and potatoes, the enterprise budget developed by the University of Idaho Extension for 2019 shows fertilizer cost accounted for almost 12% and 18% of the total operating cost, respectively. This implies that fertilizer prices are a more important factor when producers make planting decisions on barley, potatoes and wheat than alfalfa hay. A positive relationship between alfalfa hay acres planted and fertilizer prices may also be possible, in particular during higher fertilizer price periods, if producers switch acreages to alfalfa hay from other more fertilizer-intensive crops. However, alfalfa hay stands are typically held for multiple years, so fertilizer price changes may not be sustained long enough for them to matter relative to other key factors.

Given the N requirements and shares of total operating costs accounted for by fertilizer for the analyzed crops, we obtained the historical annual planted acreages and crop price data for Idaho, Oregon and Washington from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) and annual urea prices from the World Bank Commodity Markets database to investigate how these variables have evolved from 1980 to 2020. The top panel of Figure 1 shows that planted acres in the PNW for wheat and barley in 2020 were considerably lower than in 1980. Alfalfa hay and potato acres have remained relatively steady over this period. The bottom panel of Figure 1 shows the evolution of crop prices in the PNW and global urea prices. Prices of wheat and barley, and alfalfa hay to a somewhat lesser degree, have moved closely with urea fertilizer prices. The evolution in potato prices is somewhat different – while they rose in the late 2000s, they did not fall in the mid-2010s like the other prices but rather remained at the adjusted higher level.

These data were used to estimate a fixed-effects panel regression model to determine the relationship between the planted acres in PNW and prices for urea and crops. The model is specified like those in 2013 research:

area plantedt = f(area plantedt-1, crop pricet-1, substitute crop pricet-1, fertilizer pricet, trend)

where t and t-1 denote that the observation is for the current and previous years, respectively. Area planted in the previous year was included as farmers may make their planting decisions based on how much they planted last year. Crop prices in the prior year were included because farmers mostly make planting decisions only with knowledge of the previous crop year prices. The trend variable accounts for effects from factors such as technological advances (e.g., higher-yielding seeds) on acreage planted.

A positive relationship was expected between the planted area in the current year and acreage in the previous year, as well as between the acreages and own crop price. Alternatively, substitute crop prices were expected to negatively affect the planted area. Higher urea fertilizer prices were expected to decrease the crop acreages for those requiring relatively more N, including barley, potatoes and wheat but not alfalfa hay. The trend variable was expected to negatively affect planted acreages given the increasing productivity over time.

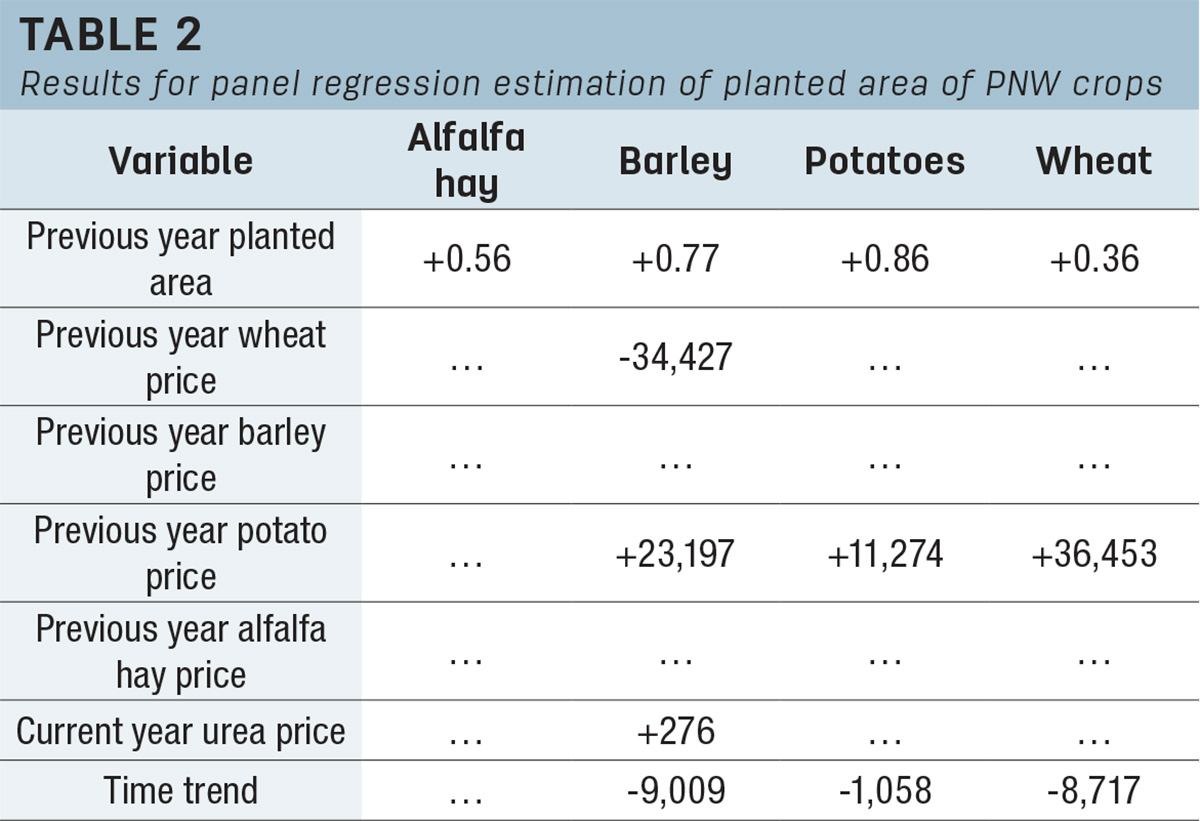

Estimation results for statistically significant coefficients are presented in Table 2.

The previous year’s planted acreage is an important determinant for all crops, but for potatoes more than others. Surprisingly, the own price (or price of the previous crop) in the previous year was an important factor only for potatoes. A possible explanation is that many of the wheat and barley acres in PNW are located in regions with few alternative crops. Barley acres in PNW are negatively affected by the previous year’s wheat prices and positively affected by last year’s potato prices. Therefore, producers may move acres out of (into) barley when wheat prices increase (decrease), and allocate more (less) cropland for barley production when potato prices increase (decrease). This may be explained by producers expecting potato prices to remain higher for multiple years and, since barley and wheat are common rotation crops for potatoes, when potato acres increase, those for barley and wheat do as well.

The magnitudes imply that if the previous-year potato price was $1 per cwt higher, then acres planted would be expected to increase by over 11,000 acres for potatoes, 23,000 acres for barley and 36,000 acres for wheat. In percentage terms for the 2020 crop year, these correspond to increased planted acres of 2.2% for potatoes, 3.5% for barley and 0.8% for wheat. Thus, the response in planted acreage to price changes is not large relative to total acres planted. Barley was the only crop with a statistically significant relationship between acreage planted and urea prices. The positive relationship implies more (less) barley acreage planted when fertilizer prices increase (decrease).

The main takeaways from this investigation are that factors influencing crop acreage decisions vary across crops, and that fertilizer prices have not been a significant predictive factor for major crops grown in the PNW over the past four decades. Own crop prices were found as an important determinant for the planted area for potatoes. Substitute crop prices were important determinants for barley (wheat and potato prices) and wheat (potato prices). Fertilizer prices were only found to have a significant positive effect on barley acres. Given that barley and wheat are main rotation crops for potatoes, and that fertilizer expenses account for a lower percentage of operating cost for barley than wheat, we may see more barley acres in the 2021-22 crop year, since both potato and fertilizer prices have been increasing leading up to the 2022 preparation and planting seasons. However, given that the fertilizer price increase so far in the latter half of 2021 is unprecedented, fertilizer prices may be more important in 2022 for the other crops than they have been over the estimation period of 1980 to 2020.

Other factors (such as the expected availability of water for irrigation) were not accounted for in this analysis but are important determinants of planting decisions for many producers in the PNW. The USDA acreage report that is scheduled for release in late June 2022 will contain survey-based planted area estimates, which will provide more definitive information for how producers made their planting decisions for the 2021-22 crop year.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

.jpg?height=auto&t=1713304395&width=285)