TRENDING TOPIC ARTICLE: HERD HEALTH This article was featured as one of our most popular herd health articles. to jump to the article below. University of Wisconsin’s Garret Oetzel and Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Inc.’s Brian Miller drilled down on the causes and effects of hypocalcemia. Many readers were likely surprised to learn that when combing clinical and subclinical cases, incidents of hypocalcemia in a 2,000-cow herd can cost a producer more than $60,000 a year. Oetzel is still providing information about the disease. Click here to read a recap of his presentation at the Four-State Dairy Nutrition and Management Conference in June, where he said nutritional management is the key to prevention.

ARTICLE

Hypocalcemia (low blood calcium) is an important determinant of fresh cow health and milk production. Five key principles shape our understanding of this common metabolic disease and how to manage it on your dairy.

- Second-lactation and greater cows have a transient hypocalcemia around calving.

- Hypocalcemia is linked to other fresh cow problems.

- Supplementation with oral calcium is the preferred approach for supporting cows exhibiting early signs of milk fever but still standing.

- Subclinical hypocalcemia has greater associated costs to your dairy than do clinical cases of milk fever.

- Even herds with successful anionic salts programs and minimal cases of clinical milk fever will benefit from strategic use of oral calcium supplements.

The start of each new lactation challenges a dairy cow’s ability to maintain normal blood calcium concentrations. Milk (including colostrum) is very rich in calcium, and cows must quickly shift their priorities to adjust for this sudden calcium outflow.

Average blood calcium concentrations noticeably decline in second-lactation or greater cows around calving, with the lowest concentrations occurring about 12 to 24 hours after calving.

A cow does not necessarily have to become recumbent (down) to be negatively affected by hypocalcemia. With or without obvious clinical signs, hypocalcemia has been linked to a variety of secondary problems in post-fresh cows.

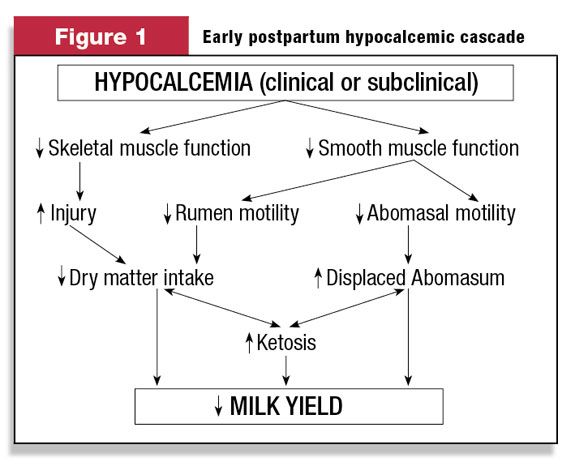

This happens because blood calcium is essential for muscle and nerve function – particularly functions that support skeletal muscle strength and gastrointestinal motility.

Problems in either of these areas can trigger a cascade of negative events that ultimately reduce dry matter intake, increase metabolic diseases and decrease milk yield. This is illustrated in Figure 1 .

Data from large, commercial dairies indicates that hypocalcemia around calving is most strongly associated with impaired early lactation milk yield, increased risk for ketosis and increased risk for displaced abomasum.

Clinical signs of hypocalcemia in dairy cattle around calving may, for convenience, be divided into three stages. Stage I hypocalcemia is early signs without recumbency. It may go unnoticed because its signs are subtle and transient.

Affected cattle may appear excitable, nervous or weak. Some may shift their weight frequently and shuffle their hind feet.

Some cows become hypocalcemic at times other than calving and exhibit clinical signs similar to those described above for Stage I hypocalcemia. Such non-parturient hypocalcemias are often triggered by periods of unusual stress or decreased dry matter intake.

This condition is most commonly seen in cows in the first two to 10 days of lactation, cows that are in heat, cows with severe digestive upsets or cows suffering from severe (toxic) mastitis.

Oral calcium supplementation is the best approach for hypocalcemic cows that are still standing. A cow absorbs an effective amount of calcium into her bloodstream within about 30 minutes of supplementation. Blood calcium concentrations are supported for about six to 12 hours afterwards.

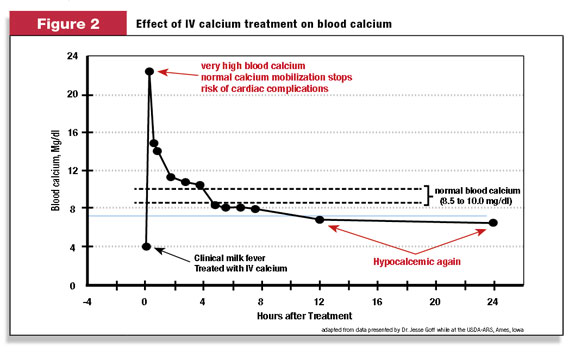

Intravenous (IV) calcium is not recommended for treating cows that are still standing. Treatment with IV calcium rapidly increases blood calcium concentrations to extremely high and potentially dangerous levels.

Extremely high blood calcium concentrations may cause fatal cardiac complications and (perhaps most importantly) shut down the cow’s own ability to mobilize the calcium she needs at this critical time. Cows treated with IV calcium often suffer a hypocalcemic relapse 12 to 18 hours later.

The problems with IV calcium treatment are illustrated in Figure 2 .

Cows in Stage II hypocalcemia are down but not flat out on their side. They exhibit moderate to severe depression, partial paralysis, and typically lie with their head turned into their flank.

Stage III hypocalcemic cows are flat out on their side, completely paralyzed, typically bloated and are severely depressed (to the point of coma). They will die within a few hours without treatment.

Stage II and Stage III cases of hypocalcemia should be treated immediately with slow IV administration of 500 ml of a 23 percent calcium gluconate solution. Treatment with IV calcium should be given as soon as possible, as recumbency can quickly cause severe musculoskeletal damage.

To reduce the risk for relapse, recumbent cows that respond favorably to IV treatment need additional oral calcium supplementation once they are alert and able to swallow, followed by a second oral supplement about 12 hours later.

Subclinical hypocalcemia (low blood calcium concentrations but without clinical signs) affects about 50 percent of second-lactation and greater dairy cattle fed typical pre-fresh diets. If anions are supplemented to reduce the risk for milk fever, the percentage of hypocalcemic cows is reduced to about 15 to 25 percent.

Subclinical hypocalcemia is associated with decreased dry matter intake after calving, decreased milk production and increased risk for ketosis and displaced abomasum in early lactation.

Subclinical hypocalcemia is more costly than clinical milk fever because it affects a much higher percentage of cows in the herd. For example, if a 2,000-cow herd has a 2 percent annual incidence of clinical milk fever and each case of clinical milk fever costs $300, the loss to the dairy from clinical cases is about $12,000 per year.

If the same herd has a 30 percent annual incidence of subclinical hypocalcemia in second-lactation and greater cows (assume 65 percent of cows in the herd) and each case costs $125 (an estimate that accounts for milk yield reduction and direct costs due to increased ketosis and displaced abomasum), then the total herd loss from subclinical hypocalcemia is about $48,750 per year.

This is about four times greater than the cost of the clinical cases.

Even herds with successful anionic salts programs and minimal clinical cases of milk fever will benefit from strategic use of oral calcium supplements. Start by supplementing all standing cows who have clinical signs of hypocalcemia and all down cows following successful IV treatment.

Depending on the herd’s incidence of hypocalcemia, it may also be economically beneficial to strategically supplement older fresh cows with oral calcium. Supplements should be given both at calving and repeated the next day, so the cow is supported throughout the time that her blood calcium concentrations are the lowest. PD

Garrett Oetzel, DVM, MS, is an associate professor at the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin – Madison ( http://www.vetmed.wisc.edu/dms/fapm/ ).

Brian Miller, DVM, is a professional services veterinarian with Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Inc. ( http://bi-vetmedica.com/cattle ).

References omitted due to space but are available upon request to editor@progressivedairy.com .

PHOTO

A cow does not necessarily have to become recumbent (down) to be negatively affected by hypocalcemia. With or without obvious clinical signs, hypocalcemia has been linked to a variety of secondary problems in post-fresh cows. Photo by PD staff.

Garrett Oetzel

Associate Professor

School of Veterinary Medicine

University of Wisconsin

www.vetmed.wisc.edu/dms/fapm