Transition from dry pregnant stage to freshening and onset of lactation causes tremendous stress in dairy cows. Cows need significantly more calcium while lactating as compared to the last stages of gestation. Colostrum and milk are loaded with calcium, and fresh cows must be able to adjust to this sudden calcium drain to maintain health and productivity. This is particularly critical for a cow’s second lactation and greater. Low blood calcium can lead to milk fever.

Milk fever in dairy cows is an economically significant disease because it increases a cow’s susceptibility to mastitis, retained fetal membranes, displaced abomasum, dystocia and ketosis, all of which can reduce a cow’s productive life.

The National Animal Health Monitoring System’s 2002 report showed overall incidence of milk fever in the U.S. at 5 percent. Depending on the level of deficiency, a cow can have clinical milk fever with classic signs, or she can be suffering from subclinical milk fever, showing only subtle signs.

Dairy cows with blood calcium concentrations at or below 8.0 mg/dl, but not showing clinical signs, are considered to be suffering from subclinical hypocalcemia. Subclinical hypocalcemia is associated with decreased dry matter intake after calving, decreased milk production, and increased risk for ketosis and displaced abomasum in early lactation. Researchers reported that 50 percent of mature dairy cows and 25 percent of first-calf heifers experience subclinical hypocalcemia.

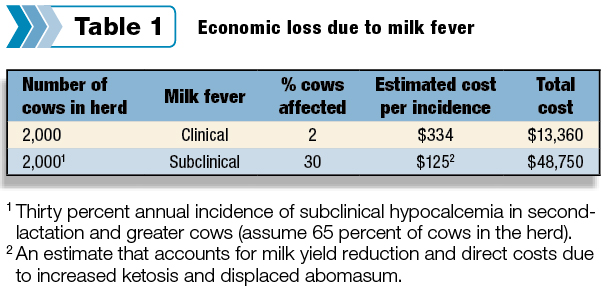

Others have estimated that the overall economic cost of subclinical hypocalcemia in a dairy herd is four times the cost of clinical cases, resulting in a substantial impact on profitability of dairy operations. This increased economic cost is attributed to the greater number of cows with subclinical versus clinical hypocalcemia, even though each individual subclinical case costs less than a clinical case.

Identification of cows with subclinical milk fever is impractical because these cows do not display classic signs. Thus, prevention is the only option for managing subclinical milk fever.

Supplementation with oral calcium is one approach for supporting cows exhibiting early signs of milk fever but still standing. Even herds with successful anionic salts programs and minimal cases of clinical milk fever will benefit from strategic use of oral calcium supplements. A cow absorbs an effective amount of calcium into her bloodstream within 30 minutes of supplementation. Blood calcium concentrations are then maintained for six to 12 hours afterwards.

Calcium chloride based gels and drenches are particularly beneficial as oral calcium supplements because these provide highly available oral calcium. Oral calcium-chloride supplements have been shown to reduce the risk of clinical and subclinical milk fever and reduce the risk of displaced abomasum.

Nutritional management combined with oral calcium supplements is essential for prevention of hypocalcemia and associated postpartum metabolic disorders in fresh cows. Oral calcium gels and drenches are critical for maintaining productivity and profitability of a dairy operation. PD

Vijay Sasidharan, DVM, is an on-staff veterinarian in research and development of new nutrition supplements at Vets Plus Inc.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

Vijay Sasidharan

Vice President of Technical Service and Export Business

Vets Plus Inc.

PHOTO

Photo by PD staff.