With genomics becoming a tool that many producers across the country are using, a new concern is now emerging – increased inbreeding depression. A webinar in early April discussed this topic as well as the launch of a new program designed to help provide a solution to this concern. After nearly four years of development, Select Sires Inc. launched StrataGEN, a program focused on providing an easy-to-use solution to help producers obtain optimal genetic progression while minimizing inbreeding within their herds.

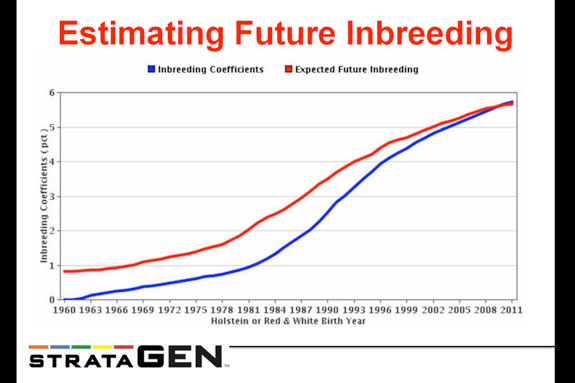

Jeff Ziegler, genomic program manager at Select Sires, reiterated the growing concern of inbreeding. He began by highlighting a chart from USDA’s Animal Improvement Programs Laboratory (AIPL) that demonstrated inbreeding coefficients calculated since 1960.

He pointed that there was no inbreeding in the Holstein population in 1960, yet today the industry is nearing a 6 percent inbreeding coefficient, which could economically impact dairy herds. “For every 1 percent increase in inbreeding, there’s about a lifetime net merit decrease of $24 or 790 pounds of milk,” Ziegler says.

He then described the pedigree inheritance model that had been used in the past to determine the gene transmission of an animal, where one quarter of an animal’s genes is transferred from each grandparent. With genomics now being available for almost three years, Ziegler says the pedigree inheritance model hasn’t been as accurate in the production ratings when looking at a pedigree analysis.

He explains that a subset of the genes actually transmitted is now taken and quantified depending on what they look like through an SNP analysis. “We can more accurately quantify the genes that are passed from generation to generation and get a much more accurate account of what these inbreeding coefficients look like,” Ziegler said.

How the program works

To start this program, the Holstein breed was broken down into five specific genetic lines, which Ziegler says was a difficult task because of the interrelation of the Holstein population. Each of these five lines is unique to itself and distantly related to the other four lines. Matings were then intensified within an individual line to develop a line-bred sire within these particular lines.

The line-bred sires are then taken to a dairy herd that has also been broken down into five genetic lines. These lines are crossed so that a highly inbred line sire is used on a highly different cow within that individual herd.

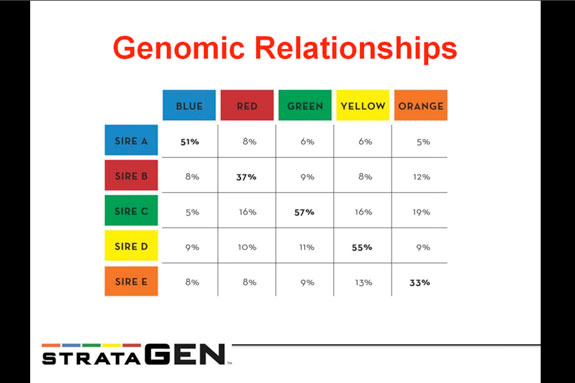

Ziegler states that these lines are represented by colors (blue, red, green, yellow and orange) as seen in the genomic relationship chart. This color-coding was a way to simplify the approach to help slow down the inbreeding process, he says.

“Basically, Sire A could be used on the red, green, yellow or orange line within that existing herd, but we would not recommend that bull be used on the blue line because it’s already highly related to that line,” Ziegler says.

According to the chart, 51 percent of the genes of Sire A are related to the blue line, whereas only 8 percent of those genes are related to the red line, and only 6 percent to the green line.

“Once the females are broken into these genetic lines, what we’re basically doing is we’re breeding simply by colors,” Ziegler says. “Taking females that fit a particular line and males that fit a particular line and we’re matching up colors.”

Breaking down individual herds

Ziegler explained that breaking down individual herds into the five lines would begin with a visit from a StrataGEN specialist who would perform a herd audit.

The audit could take place following several options such as genomic testing individual females to get an accurate account of the SNP breakdowns. However, Ziegler points out that this would be costly and time consuming.

Other options includesimple parentage tests, a less expensive option than genomic testing. If a dairy has a good DHI program with good herd records available, that information could also by compiled and sent off to AIPL to get an analysis on genomic relationships of all the animals within that particular herd.

“If there’s not a DHI program available in that particular herd, we could just simply look at semen purchases made over a given period of time,” Ziegler says. “It’s our way to say this is what the herd is represented by genetically and again send off to AIPL and break them into different genetic lines.”

After the first generation of calves is born, the program would rotate to the next color, again rotating after the second generation of calves. Following the StrataGEN program’s approach, the process would take five years to return to the existing line again, at which point the process could start over again.

“It’s quite a long process but the longer a herd gets involved in the StrataGEN program and stays with the program, the bigger the benefit simply because we’re using sires that are distantly related from one another,” Ziegler says. PD

Dario Martinez

Editor

Progressive Dairyman