Mention hybridization, and growers often think of corn. That’s not surprising since the scientific foundation to develop hybrid corn varieties has been around since the 1940s. Corn is not the only crop to undergo the hybridization process. Cotton, tomatoes and alfalfa have also significantly benefitted from the advancement of the hybridization model.

Why hybrids?

Agriculture has long known and understood the benefits of “hybrid vigor.” The mule, a cross between a donkey and a horse, is a prime example of hybrid hardiness and longevity.

In the plant world, early 20th century data from crosses between two species of jimson weed demonstrated how hybrids created plants that were twice as tall as either parent.

The hybrid process largely got its start in corn because historic corn yields were modest at best. In fact, in the early 1900s, yield gains of corn due to breeding were minimal. In the 1930s, most corn growers used open pollinated corn with an average yield of 20 bushels per acre.

Corn hybrid technology was first found in research literature in 1908 but didn’t gain much traction on-farm for several decades. In fact, less than 1 percent of corn planted in the U.S. was a hybrid variety in 1933.

However, by 1945, hybrid corn varieties took root with more than 90 percent of corn planted in the U.S. meeting the hybrid qualifications.

We are still making history today, with U.S. corn yields averaging more than 158 bushels per acre in 2013 and many impressive yields from 200 to 250 bushels per acre.

What about alfalfa?

The successful development of hybrid corn varieties has helped pave the path for hybrid alfalfa.

“There are a number of similarities in the processes, but there are a number of differences, too, many of which have to do with the biology of the plants,” explains Steve Wagner, Alforex Seeds alfalfa plant breeder.

Unlike corn, which obtains one set of genes from each parent plant, alfalfa obtains two sets of genes from each parent plant – and that’s just one of the challenges plant breeders faced in creating alfalfa hybrids.

As a result, development success remained elusive until 2001, when the world’s first hybrid alfalfa was introduced. The hybrid resulted from development of a patented breeding system that controlled pollination to create the desired outcome more than 20 years in the making.

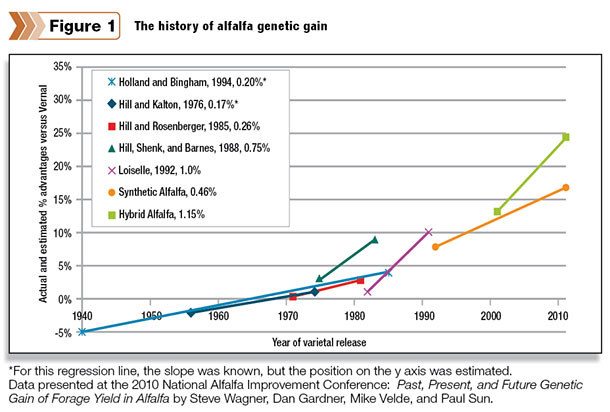

This breakthrough represented a major advancement in alfalfa breeding and consistently delivered an 8 to 15 percent yield advantage over non-hybrid competitive alfalfas – significantly higher than yield improvements achieved with conventional breeding methods.

A second generation of the hybrid was released in 2009.

Previously, most advances in alfalfa varieties were due to breeding for pest resistance through conventional methods.

When pest-resistant varieties are grown in environments where pest development is favorable, there is a marked difference between resistant and susceptible varieties, note experts at the University of Wisconsin.

However, in the absence of pest pressure, resistant varieties do not improve yield over susceptible varieties. Overall, conventional alfalfa genetic yield progress is very slow, with accumulated yield gains of about 10 to 15 percent during the last 50 years.

Generations of results

The third generation of hybrid alfalfa was released in 2013 and is possibly the most extensively tested alfalfa variety in history. This generation arrived even more quickly than the previous generation due to greater investment in the alfalfa plant breeding program and more experience.

As with previous releases, this latest hybrid provided growers with significantly increased yields, boasting a consistent 12.3 percent yield advantage versus competitive, non-hybrid alfalfa varieties.

“From corn breeders we learned that the more varieties you evaluate and test, the more genetic progress we can make,” says Wagner. Across the industry, corn breeders evaluate results from about one million plots each season.

Alfalfa plant breeders review and calculate a stunning level of data in their search for better alfalfa products. In 2012, one company recorded more than 80,000 alfalfa plot harvests and hundreds of new alfalfa parent lines have been evaluated.

Various combinations of these parent lines have resulted in thousands of potential new hybrid alfalfa varieties. In addition, “on-farm” test trials have been conducted to evaluate hybrid performance across a wider range of weather conditions, soil types and management practices than could be tested with an in-house program.

“The alfalfa hybrid breeding system is a tool to help breeders make consistent, long-term, positive incremental genetic gain,” concludes Wagner. “This means growers can produce more feed on less land, helping them become even more efficient and productive in a cost-effective way.”

Hybrid expansion plans?

Despite corn and alfalfa’s hybridization success, the technology remains a challenge in several other key field crops. For example:

- Hybrid wheat has not been successful yet. Several seed companies are working on hybridization of wheat, but commercial results are not anticipated for another 10 years or so.

- Hybrid soybeans have not been successful either. According to the Illinois Soybean Association, a number of unsuccessful attempts to develop hybrid soybeans have been made since 1979.

“The challenge lies in the biology of the plant and how the plants are naturally pollinated,” explains Wagner. “While corn is wind- pollinated and alfalfa is pollinated by bees, wheat and soybeans are self-pollinating, and that makes the process of producing a hybrid from cross-pollination very difficult.” FG

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.