In a recent three-part series, we provided perspectives and ideas on how to address bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) and related issues in dairy herds.

In the first article, we compared National Animal Health Monitoring System (NAHMS) bulk milk data with a more recent survey which found 28 percent of herds greater than 500 cows BVDV-positive with at least one BVDV persistently infected (BVDV-PI) cow.

We looked at costs associated with removing BVDV-PI animals from herds identified as BVDV-positive from bulk tank milk sampling.

We also addressed the economics of subclinical BVDV in herds versus elimination, and in the final article, reviewed the expected number of BVDV-PI animals, testing do’s and don’ts, common human and laboratory pitfalls, and the impact of BVDV congenitally infected (CI) calves.

BVDV can affect the reproductive, respiratory and digestive systems, with possibly the greatest loss impacting reproduction. Because PI cows are a constant source of virus shedding, infection spreads to other cows, resulting in increased days open and decreased milk production.

A large-scale assessment of 150,854 A.I.s found the BVDV-infection herd status increased the risk of embryonic and fetal death. This assessment included 122,697 cows in 6,149 herds from western France.

Cows in herds presumed recently infected had a significantly higher risk of late return to service (relative risk of 1.12) compared with cows in herds presumed not recently infected. Intrauterine BVDV infection is also a major economic problem. It is associated with high abortion rates, stillbirths, fetal resorption, mummification, congenital malformations and the birth of weak, growth-retarded calves.

BVDV silently drains profits and has a big economic impact on many areas of a dairy. Yet it is often a hidden threat because, individually, these effects are often masked by all of the other confounding reproductive consequences. Collectively, they are a significant cost to the dairy. As this article illustrates, one or two BVDV-PI cows can have a major impact on reproductive efficiency.

Example 1

When we see comments about reproductive efficiency being reduced due to BVDV-PI, what does that mean – or at least what does that look like? The following are real-world experiences that could happen on your operation.

The first example is from a large California dairy that identified the presence of BVDV-PI cows in the lactating herd via routine bulk tank milk testing. Reproductive efficiency was evaluated by considering cows previously confirmed pregnant but found to be open at 92 days. The result was a decline of 14.3 percent to 7.8 percent following the identification and removal of BVDV-PI cows that were causing early lactation abortions.

Example 2

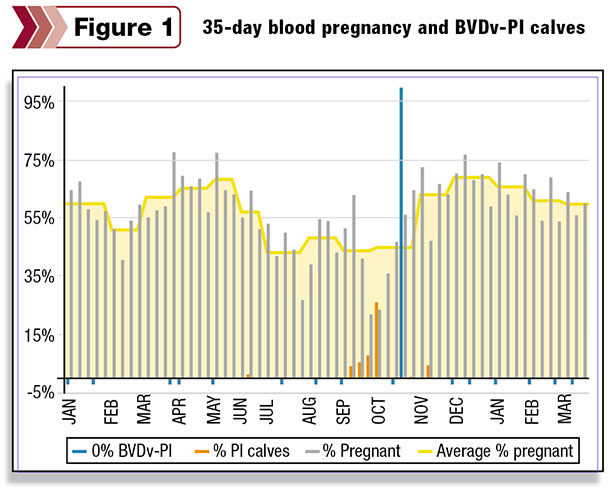

The second example illustrates data for a 1,600-cow dairy that has utilized blood pregnancy testing (28 to 35 days post-breeding) for the last 18 months. Because reproductive efficiency was lower than expected, the dairy started testing heifer calves for BVDV-PI 15 months ago.

The blue tick marks indicate when ear notches were submitted and all calves were found to be test-negative for BVDV-PI. The gray bars represent the number of pregnant cows each week, and the yellow line represents the monthly averages.

The BVDV-PI-positive animals (indicated with the red bars) were first found in late June with a large cluster identified in September and October. The weekly percentage of cows pregnant dropped to below 25 percent for the two weeks when identified BVDV-PI animals peaked in October.

The tall blue bar indicates a whole-herd screening of the lactating herd, utilizing individual blood samples from mid-October, which confirmed that the BVDV-PI cow had been removed from the lactating herd. The improvement in pregnancy rate during November and December was dramatic, and the first quarter of 2015 is trending five percentage points higher than the first three months of 2014.

Example 3

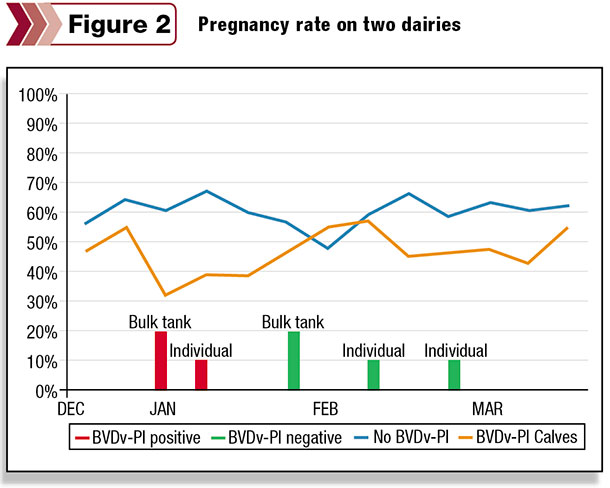

The final example is a much smaller dataset, and the dairy is early in the BVDV-PI clean-up process, but it is included to compare two “similar” dairies under the same management team that are physically a few miles apart.

The dairy represented by the orange line had a history of positive BVDV-PI bulk tank samples in 2014, whereas the blue line represents the percentage of pregnant cows for the second dairy that has been BVDV-PI negative for bulk tank milk on repeated testing.

The positive bulk tank sample and subsequent BVDV-PI-positive animal at the first dairy corresponded to a drastic decrease in pregnancy rates followed by a dramatic recovery that corresponded to the follow-up bulk tank sample, which was BVDV-PI-negative.

Newborn calves were BVDV-PI test-negative in January and February. The good news illustrated by these examples is that the positive impact of identifying and removing BVDV-PI animals can result in almost immediate results seen through improved reproductive performance.

In summary

As a disclaimer, the data provided in these examples is not from controlled studies but rather retrospective observational data following the removal of BVDV-PI animals from the lactating herd.

It is also important to understand that the presence of BVDV-PI animals is only one problem on a long list of potential problems that can negatively impact pregnancy rates. While BVDV-PI surveillance and management are not the “silver bullets,” they can be pretty “shiny.”

Identifying and removing PI animals from milking strings can increase productivity by reducing negative effects of this endemic, subclinical disease in a herd. Negative effects on reproduction can be measured and serve as an indicator of future improvements in mastitis, culling rates, slaughter value and mortality, as well as reduced milk production.

Eliminating BVDV from our dairy herds is important, but it’s just one component of a complete disease control program. Working with your veterinarian to develop proper vaccination, biosecurity and biocontainment strategies is required for a comprehensive plan. The long-term goal is always to create the best opportunity to increase, or at least maintain, overall herd efficiencies, health and profitability.

References omitted due to spacebut are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.