A somatic cell count (SCC) of 200,000 is usually the point at which a cow is considered to be infected with mastitis, and decades of research has shown there’s a pretty significant milk loss when cows reach this threshold.

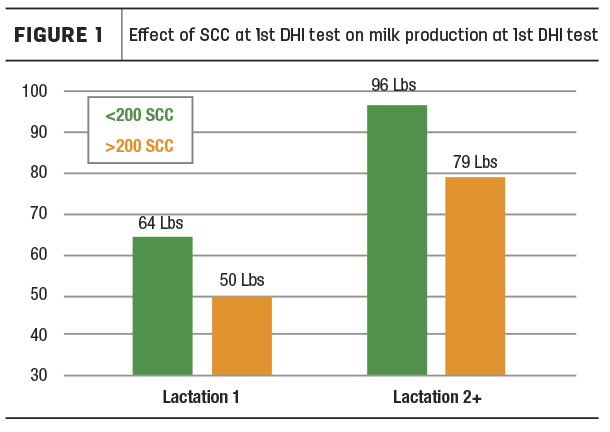

I found it interesting though, that these milk production losses seem to be magnified in fresh and early lactation cows. I evaluated the relationship between SCC and milk production at the first Dairy Herd Improvement (DHI) test in six herds, representing 11,000 cows. In these herds, if a mature cow had greater than 200,000 SCC at her first DHI test, she gave a remarkable 17 pounds less milk than a cow with less than 200,000 (Figure 1). Lactation one cows gave 14 pounds less milk if they were over 200,000 SCC.

The question then is: Why are these losses so severe for fresh cows? Could it be that the immune system is using more nutrients, essentially stealing them away from milk production? Researchers have been working hard to attempt to determine the nutrient costs of an immune response. The immune cells burn up a lot of energy during the hunting and killing process of the invading bacteria. Also, once the immune system is activated, the immune cell’s preference for glucose increases and causes them to absorb glucose directly from their surrounding environments. This competes directly with the production of milk because milk synthesis is driven by using glucose to make lactose. Some research has shown that an activated immune system can use over 4 pounds of glucose per day.

Since many fresh cows are already in a negative energy balance, any energy used by the immune system is energy that’s likely taken away from milk production. This made me wonder how cows at midlactation (about 150 days in milk [DIM]) were affected when they went over 200,000 SCC. Since most cows would be out of their negative energy balance at this time, would they lose as much milk? It turns out they didn’t. Mature cows that were over 200,000 at their fifth DHI test lost only 6 pounds and the lactation one cows lost just 5 pounds.

Having a fresh cow’s milk production reduced by 14 to 17 pounds is enough to get most people’s attention, especially because we know that this will likely set the entire lactation curve lower for these cows. However, the impact this has on the average production of the fresh group will depend on what percentage of cows are over 200,000 at their first DHI test. This will vary a lot from farm to farm, but in the six herds that I evaluated, about 14% of the lactation one cows were greater than 200,000 SCC at their first DHI test, and 18% of mature cows were over that threshold.

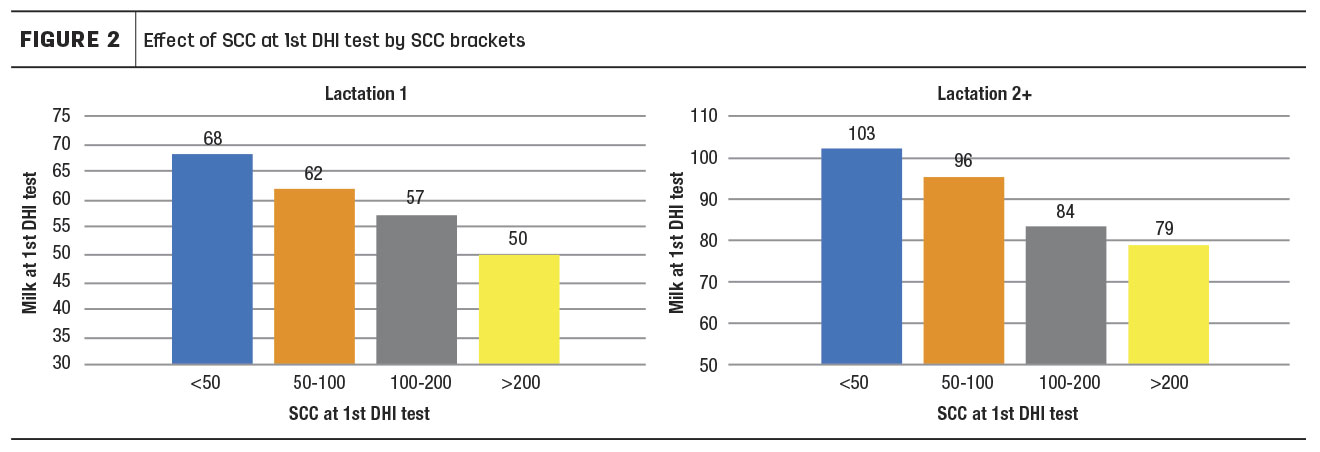

This also made me question if we truly only start losing milk when cows go over 200,000 SCC, or do the losses start at a much lower level? When we talk about losses due to an activated immune system, at what point does the immune system become activated?

I further analyzed the fresh cows in these six herds and evaluated them in SCC increments of 50,000 to attempt to find out when the milk losses actually start. In both cows and heifers, there was a large milk loss starting already at a SCC of just 50,000, and the losses steadily continued at each further increment (Figure 2). This indicates that mastitis is likely affecting more cows than previously realized, since the herds I evaluated had almost half of their cows greater than 50,000 at the first DHI.

Most likely, there are other factors that cause some of this milk production loss. Mastitis has been shown to destroy mammary epithelial cells or even just reduce their efficiency. Also, it may not entirely be due to cause and effect. We know that both subclinical ketosis and hypocalcemia impair the immune system. So a cow may be losing some milk due to her metabolic disease, which also weakens her immune system and makes her more susceptible to becoming infected with mastitis.

It’s becoming clear that setting cows up for a successful lactation requires minimizing the glucose used by the fresh cow’s immune system. This is especially challenging because the cow’s metabolic priority is to first supply the immune system with the necessary substrates to clear the system of infection. It’s not surprising that evolution has built a system that prioritizes the survival of the cow over the production of milk.

Recent herd surveys have reported that herd level SCC is one of the things most closely correlated to overall farm profitability. But thanks to many years of research and education, mastitis has become a preventable and manageable disease. There are a multitude of management factors, both pre- and post-fresh, that lower the infection rate of mastitis in fresh cows. Implementing mastitis control plans are usually not easy, but the rewards are high. ![]()

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

Ron Munneke lives in Baraboo, Wisconsin, and does management and nutrition consulting for herds throughout Wisconsin.

-

Ron Munneke

- Dairy Nutritionist

- Purina Animal Nutrition

- Email Ron Munneke