At 33% of the total U.S. dairy farm greenhouse gas (GHG) footprint, manure is the second greatest contributor of GHG emissions.

Dairies can mitigate these emissions through nutrient management planning, manure storage best practices, anaerobic digesters and evolving technologies to create new manure-based products.

Better manure management can also lead to improved water quality, another goal within the Net Zero Initiative.

Manure storage is a large contributor to methane emissions on the farm. Covering the storage allows for the biogas to be captured and burned or cleaned for renewable natural gas. Additives can also be used to reduce emissions from lagoons.

Composting is another method to minimize methane emissions from manure and can be done with dairy manure following solid-liquid separation.

Land application methods can vary in their effects on methane and nitrous oxide emissions. Following the 4Rs of nutrient stewardship (right source, right rate, right time and right place) can help in keeping the manure applied consistent with the crop’s requirements to minimize excess nutrients that could increase emissions.

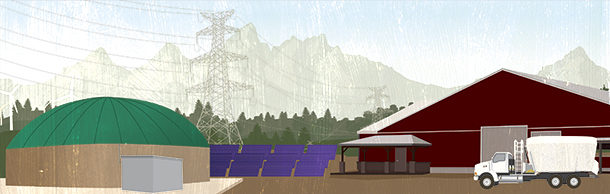

Anaerobic digesters

A well-known approach to capture manure GHG emissions on a dairy farm is with an anaerobic digester.

There are 273 manure-based anaerobic digestion systems (221 on dairy farms) operating in the U.S. today. The EPA AgStar program reports that in 2020, the country’s digesters avoided 5 million metric tons carbon dioxide equivalent of direct and indirect GHG emissions.

“Anaerobic digestion gets a lot of attention because it is an immediate impact on greenhouse gases,” says Mark Stoermann, chief operating officer for Newtrient. “The ability of the dairy industry to capture methane emissions from manure management and convert them into a usable fuel is certainly a positive development.”

It also considerably lowers odor from manure storage and homogenizes the manure stream for better nutrient recovery following digestion.

Recent policy changes and the emergence of low carbon fuel credits have stimulated growth in the number of anaerobic digesters today, but a challenge remains to make them economically viable for farms that aren’t large enough or able to connect to a natural gas pipeline.

New manure-based products

“We have the technology to capture and recycle almost all the nutrients from the manure, and use them as recycled fertilizer products,” Stoermann reports.

Technologies exist that can remove the coarse and fine solids from manure and with that 60 to 70% of the nitrogen and 80% of the phosphorus. The remaining liquid is cleaner irrigation water, and the dewatered solids are more economical to transfer to fields as fertilizer.

These technologies either require chemicals to extract the nutrients or are mechanical processes, like ultrafiltration, that require energy.

“We can recycle and capture the nitrogen and the phosphorus, but right now there are costs to do that,” Stoermann says.

While similar in nutrient content, transport and application, these new dried and pelletized manure-based fertilizers and aqueous ammonia products cannot compete economically with commercial fertilizers.

“What Newtrient is trying to do is help close that gap in costs and re-establish the circular economy that allows dairies to be more sustainable,” he says. “To be more sustainable and stay in business includes a revenue portion.”

They are working on developing markets and, with the government, regulators and NGOs, find solutions.

Until more revenue can be found, Stoermann says, “We have to continue to drive our costs down. We have to continue to look for those opportunities where we don’t have to take those nutrients as far, or where there is an opportunity to use those nutrients in a less processed state.”

Revenue potential

“We’re working on water quality credits in a couple of different states that are trying to put markets in place,” Stoermann says.

Typically, these programs have been limited to a particular stream or body of water. “It gets really difficult when you have a municipal treatment plant that’s responsible for reducing phosphorus and dairy farmers who can reduce phosphorus a lot cheaper, but those two groups aren’t running in the same circles,” he says.

Newtrient has been supportive of clearinghouse solutions that would facilitate participation and water quality transactions, resulting in cleaner water at a lower cost to all. One project is underway in Wisconsin, and they’ve worked with similar programs in Vermont as well.

“Those are opportunities that once a good model is established, we think it will be adopted by other states,” Stoermann says.

Future opportunities

There are several manure solid conversion technologies operating at a small scale that show potential.

With pyrolysis dairy manure solids are placed in a sealed chamber with no oxygen and heated to 400 to 1500°F. It results in syngas, as opposed to methane gas, as well as biochar and liquid bio-oil.

Gasification is a similar process at different temperatures and results in syngas and biochar.

Hydrothermal carbonization essentially pressure cooks wet manure to create a coal-like product called hydrochar. The remaining liquid can still be digested anaerobically.

Hydrothermal liquefaction is very similar but is done in the presence of a catalyst to create a replacement product for crude oil, as well as methane gas.

“Some of them have been up and running for years, but they’re really kind of niche right now,” Stoermann says. “They have not been fully developed.”

In addition, he says there may be opportunities to find areas on the farm that may not be productive for growing feed but could be utilized for growing biomass like switchgrass to help increase renewable energy production.

Industry resource

Newtrient offers a free, online resource with available technologies used to treat and manage manure, including evaluations and reviews of the vendors and the technology. In addition, they are building a solution-based catalog of conservation practices to reduce a farm’s environmental impact.

Stoermann also invites producers wanting more information on practices, technologies and solutions to reduce GHG emissions from manure to send an email to info to start a conversation.

“That’s why we’re here. That’s why the industry supports us, and that’s the role that we serve,” he says.

.jpg?t=1687979285&width=640)