Spontaneous combustion of hay bales is just about the worst-case scenario for any livestock producer putting up hay. That’s not the only bad outcome when it comes to hay storage. More insidious losses can come from molding and the loss of dry matter (DM), as well as nutritive value.

High-performing herds are very similar to elite athletes. A bad meal or two can knock them off the top of their game. It is much easier to create high-quality hay than to recover lost performance. In this article, we will outline options for preserving the value of hay.

Harvest hay while the sun shines

It’s not always possible to harvest at the optimal moisture levels. Too often, the sun doesn’t shine at the right time, and producers are faced with options that all seem pretty bad: Harvest now and hope the bad weather passes the field? Put up wet hay and address mold or heating later?

Putting up high-moisture hay can be accomplished while retaining nutrient value and palatability. Advancements in microbial technologies are matching – or exceeding – traditional preservative applications in terms of cost.

Propionic acid: The good, the bad and the rusty

Preservatives are applied to the hay as it is harvested to prevent heating and spoilage. The most common preservative is propionic acid. For years, it was the best option most producers had. When applied at the correct rate, propionic acid inhibits the growth of aerobic microbes within the hay. That action reduces microbial respiration, diminishes the accumulation of heat and helps limits losses of DM and reductions in nutritive value.

To work effectively, propionic acid must:

• Be applied uniformly

• Be applied at the appropriate rate

• Be used for hay under 35% moisture

The amount of propionic acid required varies from 8 pounds per DM ton for hay with less than 18% moisture to 20 pounds per DM ton for hay with over 25% moisture – that’s pounds of propionate, not total product. Often, propionic acid is not applied at the correct rate. This can lead producers to wrongly assume they are getting all the benefits of properly preserved hay. In addition, producers may not adequately compare costs between preservative options.

Propionic acid is well-known for its handling requirements. It is corrosive and can cause damage to machines and people. Buffering can help reduce the risk of corrosion – but it also requires greater quantities to be effective. Producers choosing propionic acid should flush tanks and clean surfaces on all equipment after application, including pumps, fittings and nozzles.

In addition, studies using propionic acid-based preservatives for large round bales have not been favorable.

Microbial inoculants: Now targeted for hay

Forage inoculants are strain-dependent and contain live bacteria that are specifically selected to thrive in a hay-making environment and help preserve hay. Due to this specificity, the same inoculant cannot be used in both a silage bunker and on hayfields. The strains must be targeted to overcome the specific microbial challenges of the environment.

Microbial candidates for hay preservation should:

• Be safe to use and apply

• Be able to survive in the hay matrix

• Be able to grow at low moisture levels

• Grow both aerobically and anaerobically

• Grow across a wide range of pH and temperature levels

• Inhibit or limit fungal development

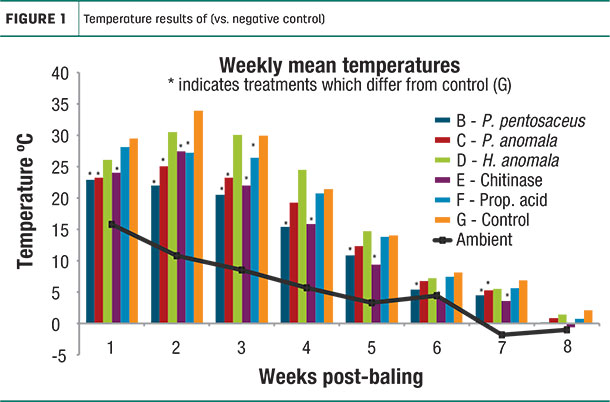

In a study of hay preservatives in Alberta, Canada, four treatments on third-cut alfalfa/bromegrass hay were compared to propionic acid. In one group, Pediococcus pentosaceus NCIMB 12675 was applied at 106 cells per gram of hay. In another treatment group, propionic acid was applied with 68% propionic acid at 2.7 liters per ton. Other treatment groups included different preservative applications, including the microbial strain Pichia anomala and chitinase.

The results showed that P. pentosaceus NCIMB 12675 kept hay temperatures the lowest throughout the eight-week trial – outperforming propionic acid.

Microbial inoculants are live, viable microorganisms and should be handled with care. However, inoculants aren’t corrosive to equipment.

Conclusion

Producing high-quality hay requires crop management and good harvesting practices. However, there are options for producers up against the weather. Using a research-proven, quality hay inoculant is one of the most cost-effective ways to preserve the value of hay, which helps ensure livestock maintain intake and performance.

Andy Skidmore received his DVM from Kansas State University and his Ph.D. in animal sciences from Cornell University and is employed by Lallemand Animal Nutrition, North America as a technical services – ruminant team member, since 2016.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.