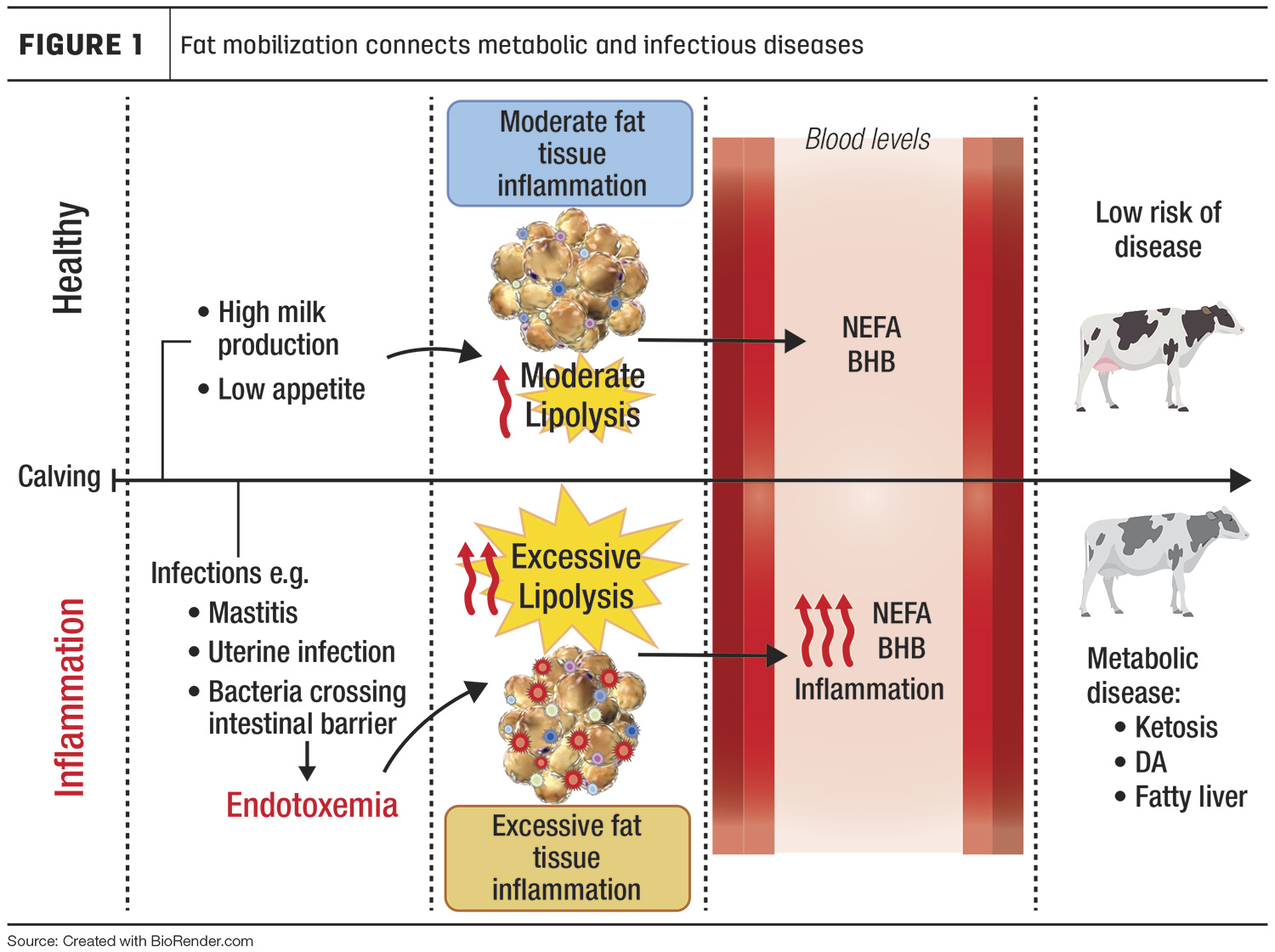

Transition cows are at higher risk for infectious (e.g., mastitis, pneumonia) and metabolic diseases (e.g., ketosis, displaced abomasum). Consequently, any management or nutritional "hiccup" in close-up or fresh cow pens is rapidly reflected in the number of sick fresh cows within days or weeks following the event. Further complicating matters, transition cow diseases often present as complexes of metabolic and infectious diseases: a common case being a cow with a retained placenta that develops ketosis a few days later. How are these diseases connected and what causes their high rates of recurrence? One of the answers is fat mobilization.

Transition cow fat mobilization: More lipolysis, less lipogenesis

The transition period is characterized by limited energy availability due to hormonal and behavioral (e.g., low appetite) changes associated with calving and the sudden increase of energy output to produce milk. Fat mobilization includes the metabolic processes that cows use to either store or release fatty acids within the fat cells. Fat mobilization includes lipogenesis and lipolysis.

Lipogenesis is the assembly of triglycerides from fatty acids and glycerol in the fat cell. In contrast, during lipolysis, enzymes in the fat cells break down the triglycerides and release free non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA). During the transition period, lipolysis is rapidly increased, and lipogenesis is shut down. As a result, NEFA are released into the blood. Normally, lipolysis decreases and lipogenesis replenishes fat depots' triglyceride reserves as lactation progresses; however, cows that mobilize too much fat are more susceptible to diseases such as ketosis, displaced abomasum and fatty liver.

Healthy fresh cows mobilize fat reserves by increasing lipolysis and reducing lipogenesis (Figure 1). Lipolysis releases NEFA that can be converted to ketone bodies (BHB) in the liver. Healthy cows have moderate lipolysis that induces minimal inflammation in the fat.

Lipolysis is triggered by bacterial infections

During infections caused by bacteria, the immune system breaks down these organisms into small remnants known as endotoxins. As a result, endotoxins may enter the blood leading to a process known as endotoxemia. During toxic mastitis caused by coliform bacteria, for example, immune cells kill the bacteria and the levels of endotoxin rise rapidly in the blood. Another disease associated with endotoxemia is subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA), during which a rapid decrease in rumen pH kills gut bacteria and, following damage to the rumen wall, endotoxins are released into the blood. When acute, endotoxemia causes severe fever, dehydration and systemic inflammation, and can lead to death – as often observed in cows with toxic coliform mastitis. While cows with mild endotoxemia often survive without exhibiting severe signs of systemic inflammation, these animals become more susceptible to additional metabolic and infectious diseases.

We recently discovered that endotoxins stimulate lipolysis in cows’ fat tissues, which may, in part, explain the high prevalence and recurrence of infectious and metabolic disease complexes in transition animals. During endotoxemia, endotoxins bind to specific receptors on fat cells known as toll-like receptors (TLR). TLR activation triggers lipolysis directly by stimulating hormone-sensitive lipase, the key enzyme that breaks down triglycerides. In addition, interleukin-6, a signaling molecule secreted by white cells during inflammation, is also capable of activating hormone-sensitive lipase during endotoxemia. Based on these findings, there is a connection between inflammation and fat mobilization in cows during diseases associated with endotoxemia.

As shown in the bottom panel of Figure 1, sick fresh cows may present bacteria or bacterial remnants (endotoxemia) in their blood, leading to excessive lipolysis (high NEFA and BHB) and inflammation in fat tissues. This inflammatory status increases the risk for metabolic diseases.

Endotoxemia and fat inflammation

Fat tissues contain leukocytes. Among these immune cells, macrophages are the most abundant. Depending on their function, macrophages are classified as pro-inflammatory (M1) or anti-inflammatory (M2). Macrophages initiate and resolve inflammation in the fat. M1 are in charge of recruiting immune cells and removing cell debris from dead fat cells. During cases of endotoxemia, cows have more M1 recruited into the fat, leading to fat inflammation. Remarkably, cows with ketosis and displaced abomasum have a very high number of M1 macrophages in their fat. Therefore, it is likely that infectious diseases that trigger systemic inflammation initiate local inflammation in fat tissues, increasing fat mobilization.

How does this change the way we treat cows with metabolic disease?

The fact that infectious/inflammatory diseases can predispose to metabolic conditions and vice versa, highlights the importance of practicing a thorough clinical exam of sick cows. Too often, the diagnosis of clinical ketosis in fresh cow pens is limited to screening for low milk production, off-feed cows, a positive reading of ketone bodies using urine or blood strips, and auscultation for detecting displaced abomasum. This routine leaves out checking for fever, clinical mastitis and signs of pneumonia.

When cows show symptoms of endotoxemia, such as fever, it is important to consider alternatives to mitigate inflammation, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Reducing the inflammatory response in fat tissues will limit lipolysis intensity and limit the risk for developing clinical ketosis and other inflammatory diseases. Nutritional supplements that inhibit lipolysis, such as niacin, can also be used to treat clinical ketosis as these reduce NEFA concentrations and aid in reducing inflammation in fat tissues.