The following is the first part of a two-part series of articles regarding freestall design and its impact on the cow’s comfort and health. The dairy expansion era in North America, which gathered pace throughout the 1990’s and continues to this day, has resulted in the migration of dairy cattle from traditional tiestall and stanchion barns to the freestall facility, which has emerged as the dominant form of dairy cattle housing worldwide. The basic premise of milking more efficiently through a parlor, while being able to keep larger groups of cows together in management groups in larger herds, is sound from a management and economic perspective.

Cows are “free” to move between a feedbunk where a total mixed ration is available every hour of every day and a stall designed to provide her ample rest on a clean, dry, comfortable surface. This is the ideal – the question is whether it is the reality.

Freestalls and time budgets

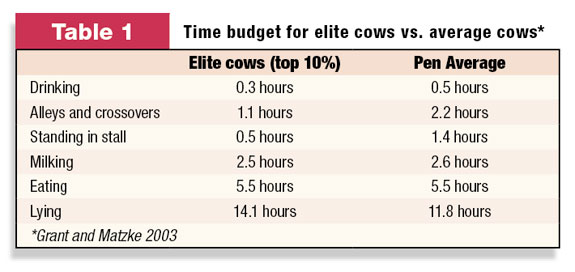

So, what do cows do in the freestalls that we have built over the last 10 years? From an analysis of 250 total 24-hour time budgets we have collected from 208 cows housed in 17 freestall barns in Wisconsin, the average time spent performing each of five key behaviors is shown in Table 1 .

On average, cows spend 2.6 hours per day milking – reflecting the 3x-milking schedule most large freestall dairies operate at. Other components of the cow’s day are also fixed and non-negotiable.

The cow has to spend a large portion of the day eating. The TMR-fed, freestall-housed dairy cow eats for an average of 4.4 hours per day (range 1.4-8.1). Note that this is about half the time that a grazing cow spends eating per day – pasture cows average around 8 to 9 hours per day eating.

She also needs to drink around 20 to 25 gallons of water per day (more in hot climates) and she will spend an average of 0.4 hours per day at or around a waterer. With these fixed, non-negotiable time slots, we have already taken 4.4 + 0.4 + 2.6 = 7.4 hours out of the time budget, leaving under 17 hours remaining in the pen.

Time left in the pen will be spent performing three activities – lying down, standing in an alley and standing in a stall. The average freestall cow spends 2.4 hours per day standing in an alley socializing, moving between the feedbunk and stalls and returning from the parlor.

Once in the stall, the average cow spends 2.9 hours per day standing in the stall (range 0.3-13.0) and 11.3 hours per day lying in the stall (range 2.8-17.6) on average – but note the wide ranges in these behaviors.

Lying behavior is typically divided into an average of 7.2 visits to a stall each day (called a lying session), and each session is categorized by periods standing and lying – called bouts. The average cow has 13.6 lying bouts per day and the average duration of each bout is 1.2 hours (range 0.3-2.9). Most cows will stand after a lying bout, defecate or urinate, and lie back down again on the contra-lateral side.

From studies designed to make cattle work for access to a place to rest, it would appear that cows target around 12 hours per day target lying time, and this is in agreement with the lying times found in well-designed freestall facilities. If this is the case, then our industry is failing to provide the average cow sufficient rest, and our freestall ideal is not being realized.

What is the cost of inadequate rest?

It is commonly suggested that cows make more milk when they are lying down, as blood flow through the external pudic artery increases by around 24 to 28 percent when lying compared to standing up, and failure to achieve adequate rest has negative impacts on lameness, ACTH concentrations, cortisol response to ACTH challenge and growth hormone concentrations – suggesting there is a significant stress response.

Some workers have suggested there is a linear relationship between time lying and milk production of the order of 2 to 3.5 lbs of milk increase for each additional hour of rest. While this may be true, we have not seen such a relationship, and milk yield has not been significant in any of the lying time models in our time budget studies.

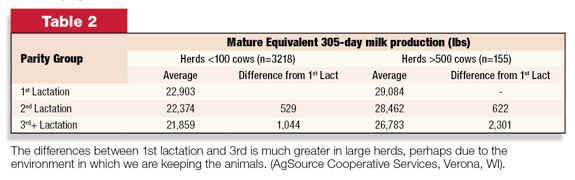

It seems more likely that the requirement for rest is a threshold event and that all cows, regardless of yield, require a minimum period. A strong case can be made that the true cost of failing to achieve this rest is an increase in lameness, and lameness has significant impacts on production ( Table 2 ).

So what can we do to improve the situation? We can certainly make sure there is adequate time for rest by limiting time out of the pen for milking, providing enough stalls for cows to achieve their target rest by limiting overstocking and finally, by making sure that the stall is comfortable and easy to use.

The importance of stall surface

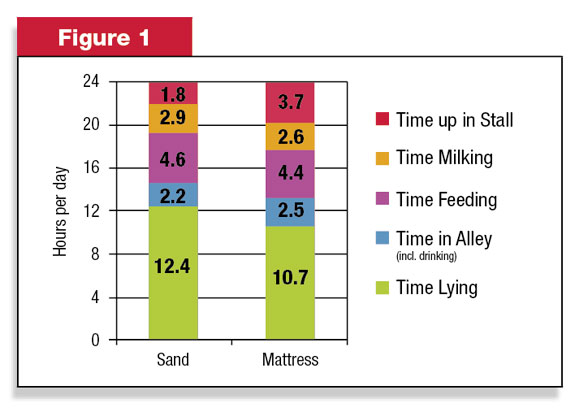

Analysis of our time budget database highlights the importance of stall surface. Cows bedded on sand exceeded our target of 12 hours per day of rest, while cows on rubber crumb-filled mattresses averaged only 10.7 hours per day ( Figure 1 ).

The reason for this is two-fold. Firstly, there are on average 42 percent fewer lame cows in sand-bedded freestall herds, and secondly, lame cows stand longer in mattress stalls compared to sand stalls. We believe the main reason for this is due to the difficulties lame cows have rising and lying down on a firm surface.

While sand provides cushion, traction and support – which facilitates rising and lying movements for lame cows, enabling them to maintain normal patterns of rest – firm mattress surfaces make it difficult for cows to rise and lie down because of the pain associated with the contact point between a painful foot and a firm, unforgiving surface.

As a result, we see an extension in standing time per day, a reduction in the number of visits to a stall per day and, as a consequence of 3x-milking and other stresses to the cow’s time budget, a reduction in lying time. Failure to provide adequate rest and recuperation for lame cows results in chronic disease and an increase in the prevalence of lameness.

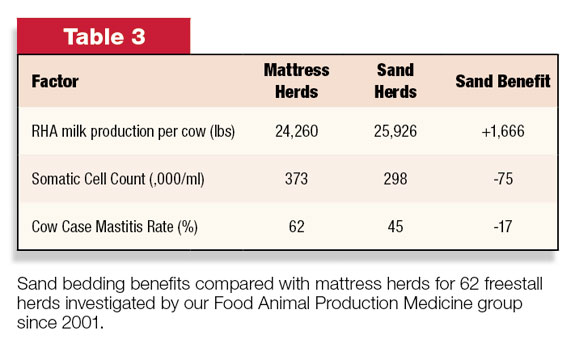

The difference in lameness prevalence is the main reason for the large difference in milk production observed between sand and mattress freestalls ( Table 3 ), but there are also benefits in terms of milk quality. The numbers presented in Table 3 are for herds visited because of an udder health problem.

However, the differences observed are very typical of the mattress-to-sand conversions we have been involved in over the last five years, and we use these figures for the construction of partial budgets to finance the barn changes.

Sand must be managed to prevent a buildup of organic material over time. Provided fresh sand is added once or twice a week, gross contamination is removed each milking, the bed is leveled daily and sand is removed from the rear of the beds every six months or so, it remains the gold standard for the cow, not only in terms of comfort but also in terms of milk quality.

While organic bedding materials may be “managed,” I find them in every way inferior to sand, particularly when managed in a deep, loose bed.

Because sand is so forgiving it has often been said that the cow may compensate for other failures in stall design – such as inadequate space. In fact, I used to think the same – but I do not anymore. We have seen too many improvements in production and health in sand-bedded facilities when other stall design improvements have been made. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request to editor@progressivedairy.com .

—Excerpts from 2009 Four-State Conference

Nigel B. Cook

Clinical Assistant Professor

University of Wisconsin

nbcook@wisc.edu