The amazing ability of New Zealand farmers to turn grass into cash has fascinated many of us forage fanatics. So in late October and early November 2016, a group of 22 people from nine states across the U.S. jumped at the opportunity when the American Forage and Grassland Council organized a New Zealand tour. Along the way, we learned a lot about their pasture-based dairy industry.

Dairy is king in New Zealand

Known for its high productivity and favorable climate, New Zealand has been a major agricultural exporter since its early days as a country. This has been particularly true for dairying. New Zealand is roughly the size of Colorado with a population of just over 4.7 million, but they have around 6 million dairy cows.

Over 90 percent of New Zealand’s annual dairy production is exported, and the value of those dairy exports totals over $10.8 billion each year. For perspective, their total gross domestic product is estimated to be $180 billion, and those dairy exports account for around 20 percent of their $54 billion in total exports. Needless to say, dairy is king in the land of the Kiwi.

Dairying is never easy, but dairying in New Zealand has its advantages. Fonterra, the cooperative run by Kiwi farmer-shareholders, processes and sells well over 90 percent of New Zealand’s milk. Under excellent management, Fonterra has managed to leverage this volume such that it now holds a commanding 30 percent market share in the world dairy export market.

In addition to garnering excellent milk prices, Fonterra’s management results in enough black ink to ensure dividends are paid to the shareholders in good years and in years of negative cash flow.

In addition to Fonterra’s marketing prowess, Kiwi dairymen are supported locally with an unrivaled infrastructure of consultants, genetic improvement products, farm supply stores, veterinary services, farm financial advisers, agricultural contractors and other service providers. These intangibles are hard to put a price on but certainly add value.

The expansion era

The historical “grass-only” model of milk production in New Zealand has largely gone away (Figure 1).

Click here or on the image about to view it at full size in a new window.

Now the most common dairy system in New Zealand is a hybrid, pasture-based system that feeds substantial amounts of ryegrass baleage and corn silage grown on the farm. Though rare, there are now a few dairies in New Zealand that are housed full time.

Still, most dairy cows in New Zealand will take 60 percent or more of total dry matter intake as grazed pasture, but production is pushed with corn silage and brought-in feed. All of these changes increased their cost of production.

Historically, New Zealand has seen few rivals to their claim as the least-cost milk producer in the world. Now, their cost of milk production is not too dissimilar to our high-input/high-output dairies in North America. With greater inputs, New Zealand dairy output has increased by nearly 50 percent in less than 10 years. Profitability increased – at least until the dairy market pendulum swung back.

Support from within

Keep in mind, there are no safety nets for dairy farmers in New Zealand. Their government removed all subsidies, tax breaks and price supports in the mid-1980s. Even the extension service was axed. The New Zealand government’s cuts were viewed by many as draconian at the time, but the industry recovered relatively quickly from the shock.

It forced the various agricultural sectors to become self-sufficient, and one would be hard-pressed to find any Kiwi dairyman longing to have government aid back.

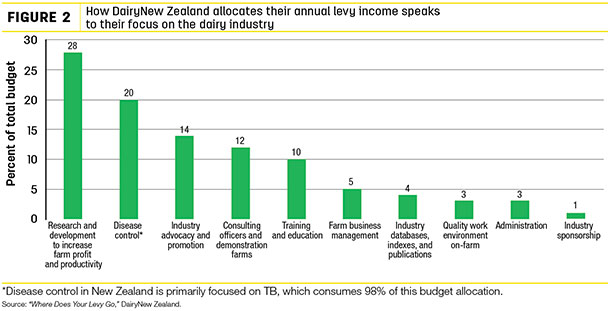

To provide most of the services lost in the cuts, the dairy industry developed DairyNew Zealand. DairyNew Zealand is an agency funded by, focused on and guided by the dairy industry. A levy of $0.026 is assessed on every kilogram of milk solid processed in New Zealand, and a board of farmers and industry advisers directs DairyNew Zealand’s activities to benefit the farmer and industry (Figure 2).

Click here or on the image about to view it at full size in a new window.

DairyNew Zealand reported a total levy income of about $45 million in the 2013-2014 season. The levies are renewed by a farmer-only referendum every six years. The outcome of the referendums demonstrates their popularity. The latest vote was in May of 2014, and the referendum passed with 82 percent of Kiwi dairy producers voting in favor.

‘Dirty dairy’

Not long ago, a Kiwi dairyman in the Waikato region of New Zealand’s North Island would quietly take pride in the claim that their region had more dairy cows per hectare (or acre) than anywhere else in the world. Today, that title is a burden.

News media reports and television ads that link pollution, water shortages and global climate change to the dairy industry are now commonplace in New Zealand. Often, specific farms are singled out and prosecuted in the court of public opinion, if not the real one.

The overused “dirty dairy” phrase is such a common expression among the urban and suburbanite “townies” in New Zealand that it now has its own Wikipedia entry.

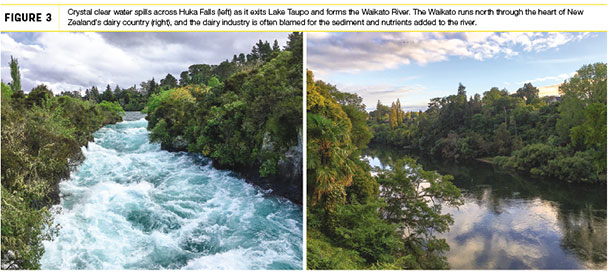

Environmentalists have focused primarily on nutrient loading in streams and rivers, since clean water is a cause all Kiwis can get behind. Kiwis are rightfully proud of their pristine countryside, crystal-clear rivers and brilliant blue lakes (Figure 3).

Click here or on the image about to view it at full size in a new window.

New Zealand is one of the most scenic countries in the world, and that attracts tourists and their money. The tourism industry is an important economic driver in New Zealand, a close second to agriculture. Consequently, there is an increasing amount of regulation on water usage, stream protection and nitrate leaching.

At the table or on the menu

In contrast to usual practice in the U.S., New Zealand’s regulatory councils take into consideration concerns about regulatory methodology voiced by farmers and researchers. Farmers frequently serve on these councils and voluntarily participate in regulatory commissions. This participatory approach allows the farmer to have a voice and put a face to the regulations being considered.

Engagement in the process has given the farmers a chance to examine the data behind the assumptions driving regulatory policies and collect data to challenge the validity of that data. As one of the farmers put it, “I feel I have to have a seat at the table. Otherwise, I may be on the menu.” ![]()

PHOTO 1: Dairy systems in New Zealand have intensified from the grass-only, low input system (top) to hybrid systems where the cows are fed a silage or concentrate supplement on a feed pad (middle). Though still rare, there are several freestall, fully confined feeding systems (bottom), including some that have robotic milkers.

PHOTO 2: Crystal clear water spills across Huka Falls (left) as it exits Lake Taupo and forms the Waikato River. The Waikato runs north through the heart of New Zealand’s dairy country (right), and the dairy industry is often blamed for the sediment and nutrients added to the river. Photos provided by Dennis Hancock.

-

Dennis Hancock

- Extension Forage Specialist

- University of Georgia

- Email Dennis Hancock