With each passing year, new additional traits are developed and made available. It can be a lot to keep track of, even for the most interested person. How can you tell if a new piece of information is something you should incorporate into your herd’s breeding program or if it is just more noise that might distract from your goals? Hone in your breeding goals, and learn which tools you really need in your toolbox when it comes to dairy cattle genetic evaluations.

Start with the basics

What type of trait are you looking at? Is it an individual trait (expressed as a PTA or STA), a selection index composed of a group of traits or a label the animal earned based on meeting criteria specified by an organization? Is there a published reliability value for the trait?

- Predicted Transmitting Abilities (PTAs) and Standardized Transmitting Abilities (STAs) – PTAs and STAs are the primary ways individual genetic traits are expressed in the U.S. PTAs are an estimate of the genetic superiority (or inferiority) that a sire or dam will transmit to their offspring for a given trait, and most traits you will see in a sire catalog are expressed as PTAs. PTAs are typically expressed in units of the trait (e.g., pounds of milk or months of Productive Life), and the range (distribution) of PTAs are similar to the differences seen in the traits’ units.

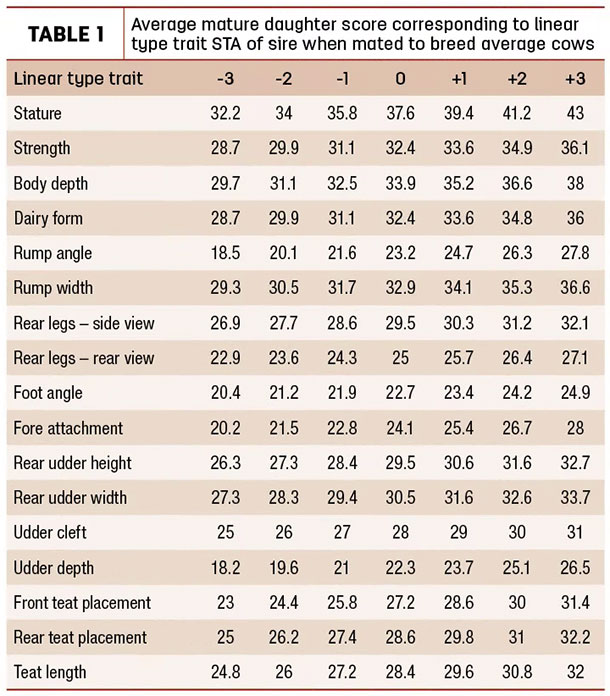

STAs are a way to remove the distribution differences between traits. The most common example can be with conformation traits (Table 1).

Even though traits like Stature and Rear Legs – Side View are measured on different scales, because they are standardized, users of the information can easily see how extreme a bull is for a trait. When looking at STAs, a value of zero is equivalent to breed average for the trait. A common misconception with conformation traits is that zero is equivalent to the intermediate value for that trait, but that is not the case.

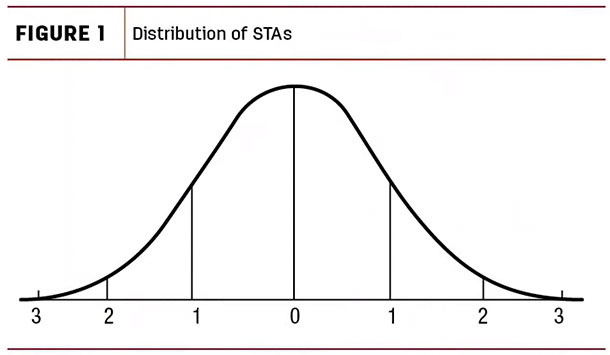

STAs are distributed on a bell curve, with the greatest number of animals close to breed average and fewer at the extremes (Figure 1).

Sixty-eight percent of the animals will have an STA value for a given trait between -1.0 and +1.0. Ninety-five percent have values between -2.0 and +2.0, and 99 percent are between -3.0 and +3.0.

Sixty-eight percent of the animals will have an STA value for a given trait between -1.0 and +1.0. Ninety-five percent have values between -2.0 and +2.0, and 99 percent are between -3.0 and +3.0.

-

Reliability – Another piece of information to look at when evaluating PTAs is the reliability value. Reliability is a measure of the accuracy of a PTA, based on the amount and quality of information included in a genetic evaluation, and is an indication of how much confidence can be placed in an evaluation. A newborn calf will have much lower reliability values than one that has been genomic tested.

A young genomic-tested bull (with no milking daughters yet) will have lower reliability values than a proven bull with hundreds of milking daughters contributing information to his genetic evaluation. The lower the reliability for a trait, the higher likelihood that it will change as more information is added to the evaluation. This is not to say that bulls with lower reliability values should not be used, but they should be used in a way that manages the risk involved, such as using fewer units each of a larger variety of bulls.

- Selection indexes – Selection indexes, such as the Total Performance Index (TPI), are powerful tools that combine many economically important traits into one value that can be used to quickly sort breeding stock. When looking at selection indexes, it is important to know what traits are included and what relative emphasis is placed on each trait.

Many companies use designations to help dairymen easily identify bulls that might be of interest. Like selection indexes, it is important to understand what goes into a bull earning that designation. Designations based solely on phenotypes (observed characteristics) are inherently less reliable for predicting offspring performance than a genetic prediction (PTA or STA) for a similar trait.

Digging a little deeper

When evaluating traits and comparing them to one another, be sure the comparison is “apples to apples.” For example, there are many traits representing mastitis resistance, available from different sources. Although named very similarly, these traits are all based on different datasets of varying sizes, maintained by different organizations, so they cannot be compared directly. This is where research comes in to determine which values are most applicable to your herd’s breeding goals.

Controlling costs on a dairy farm by selecting for healthier, more fertile, longer-lived cattle is just as important as selecting for cattle that will produce at the highest level. When evaluating traits, consider if they are economically important to your individual farm or if you expect they will be in the future. For example, interest in milk proteins, like kappa casein and beta casein, is growing. Care should be taken in placing selection emphasis on those traits to ensure they are not at the expense of economically important traits such as production, health and fertility, if you are unsure whether you will personally see a direct economic benefit in the short term.

Applying this information in your own herd

To make genetic progress and breed a more profitable herd, select traits you want to emphasize wisely. The more traits you have as a part of your breeding goals, the slower the progress you will make on each individual trait. The major selection indexes available today are a great starting point.

Be sure you are not placing double emphasis on a trait, for instance, including both Daughter Pregnancy Rate (DPR) and the Fertility Index (of which DPR is a part of) in your selection criteria.

We live in an exciting time with rapid innovation and a great deal of emphasis being placed on genetics as “the next frontier” in helping herds achieve maximum profitability. It is critical for dairy farmers to be informed and utilize all the tools available in their “genetic toolbox.” ![]()

Lindsey Worden is the executive director of Holstein Genetic Services. Email Lindsey Worden.