This time period is the last 21 days of gestation prior to calving and is a pivotal time to set the cow up for success for its next lactation.

Several advances have already been made to dry cow rations in order to help prevent metabolic problems, but there is still room for opportunity. Previously, dry cow rations have been balanced for crude protein, but new data suggests that for a successful transition after calving, it needs to go a step beyond that.

What happens during the last 21 days of gestation?

During the close-up period, the cow’s nutritional needs change drastically. A significant amount of fetal growth happens just prior to calving. In fact, approximately 70 percent occurs during the last 60 to 70 days of pregnancy. Mammogenesis, mammary gland development, is also occurring in order to prepare for lactation. These changes require more protein and all occur while dry matter intake (DMI) is typically most variable and dropping prior to calving, causing the cow to have variable or decreased protein intake. The cow starts mobilizing protein two weeks before calving and continues until about six weeks post-calving. This not only affects the energy status of the cow but also the protein balance.

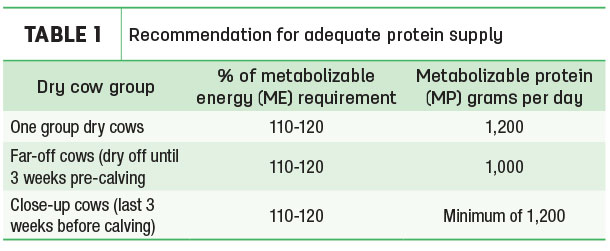

By supplying the close-up dry cow with adequate metabolizable protein (MP) without greatly exceeding the energy requirement, the cow can increase the nitrogen retention in its tissues, thereby decreasing the amount of protein mobilization before calving. This puts the cow at a better protein status at calving and helps maintain that protein status just after calving when DMI is low and the cow is susceptible to transition challenges.

The cow uses that mobilized protein for milk protein synthesis and, to a lesser extent, the production of glucose or energy. Protein and amino acids play a central role in many physiological functions, including immune system function and cell renewal.

The transition cow is under great stress and is at greatest risk for infectious diseases during the last 21 days of gestation and the first 21 days of lactation. Insufficient dietary protein supply can put stress on the immune system and can result in post-calving issues such as retained placenta, mastitis, metritis, poor colostrum quality, and poor production and reproduction performance.

What protein does the cow need?

Attention needs to be made to the source and quality of the protein, not just the amount of protein in the ration. Advancements in the models for ration balancing have made it possible to estimate the MP supply and needs of dry cows, while the use of crude protein continues to remain important. This gives nutritionists the opportunity to formulate diets for dry cows based on MP and amino acids.

MP is defined as the true protein, and the amino acids that make up that protein are available for digestion and absorbed by the intestines. Therefore, the amino acid, or the building block of the protein, is the nutrient the cow requires. Metabolizable protein is a better reflection of protein supply to the cow, and it typically comes from a combination of three sources:

- Microbial crude protein is synthesized in the rumen, and production relies heavily on a balance of adequate rumen-degradable protein (RDP), which is the protein broken down within the rumen and fermentable carbohydrates in the diet.

- Rumen-undegradable protein (RUP) is the protein from the feed that passes through the rumen without being degraded by the rumen microbes.

- Endogenous crude protein, the lesser of the three sources, is the protein from sloughed cells within the cow, etc.

Typically, these goals can be met with 12 to 15% protein diets. There is no benefit to feeding more than the recommended amount of protein. In a lactating cow, the rumen microbes will supply some MP if there are adequate fermentable carbohydrates and nitrogen supplied in the diet.

Since dry cow diets are low in energy and therefore have a limited amount of fermentable carbohydrates, especially starch, a RUP product or rumen-protected amino acids typically need to be included in the diet in order to achieve the appropriate amount of MP and amino acid profile to meet the dry cow’s requirements.

Success for the next lactation begins during the dry period. Protein plays a pivotal role in many of the cow’s biological processes. This makes the close-up dry period an especially crucial time to ensure rations are delivering cows with adequate MP in order to have a successful start to their next lactation. ![]()

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

-

Angie Manthey

- Dairy Nutritionist

- Hubbard Feeds

- Email Angie Manthey