Editor’s note: This is the final article in a four-part series about how an Oregon dairy farmer is making robots work on a grazing system. Read the three other articles How we milk 3 times a day with robots for success, Robot repairs: The solution or the problem? and Keeping milk-quality forage coming throughout your harvest season.

We graze and milk cows with robots three times a day. Experts say it can’t be done whether in North America or New Zealand. But it needs to be done.

In today’s labor market, robots are necessary and many farmers are investing in what could be a big win or a crippling failure.

Organic, but on 54 acres rather than 200, today we aim to graze on average 50% of our dry matter intake (DMI) while harvesting 52 pounds of high-component Jersey milk during a 180- to 200-day grazing season on our farm in Oregon’s Willamette Valley.

We were inspired to write this series to, God willing, help farmers save time and money in adopting effective robotic milking systems on grazing dairies. Combined, these articles blueprint a barn- and field-proven foundation. On that you’ll build grazing infrastructure. Then with management, motivate cow movement from field to barn to maximize regrowth and utilization of milk-quality forage throughout the grazing season.

Grazing infrastructure

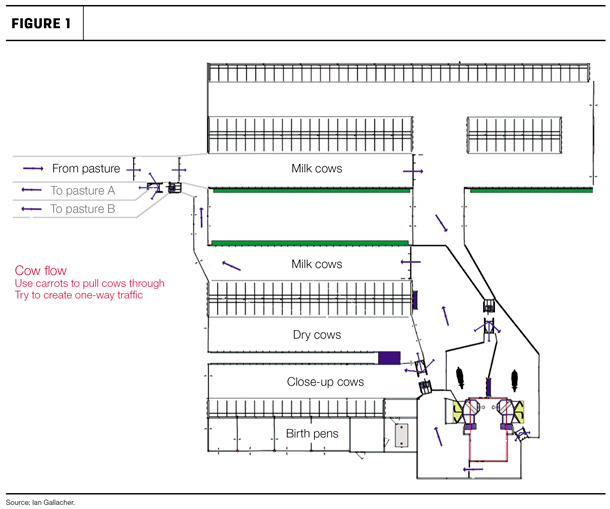

Reprinted from our first article, Figure 1 shows one-way cow traffic in our barn that extends into our pasture gate and its one-way lanes out to east paddocks and west paddocks and back into the barn.

The pasture gate and its lanes are shown in Photo 1.

It’s important cows walk from the robot to food the same way, whether it’s at the bunk or in the pasture, and that they follow straight lines to what they want rather than having to turn around and go back for it.

Initially we tried to have the barn and a lot of open space on one side of the pasture gate and the grazing lane on the other. It was a train wreck. It became a nasty bedded pack of cow manure on either side of the pasture gate. Cows would lay there waiting to go out, blocking other cows from coming in. We made the change to the lane system and it worked right away. One-way single-file traffic free from areas cows can block really made the lane system work.

The mechanics of merging both the eastside and westside incoming cow traffic into a single line of cows to go into the barn while having cows go out to the east or west at the same time were interesting and may be the subject of a later article.

The pasture gate lets us set rules that determine cow flow to and from paddocks. But more specifically, it helps us to manage our forage.

We farm forage and use cows to harvest it. That keeps feed costs lower and maintains healthy soil, healthy forage and healthy cows. The extent that our cows graze comes down to available God-given resources, work and management goals.

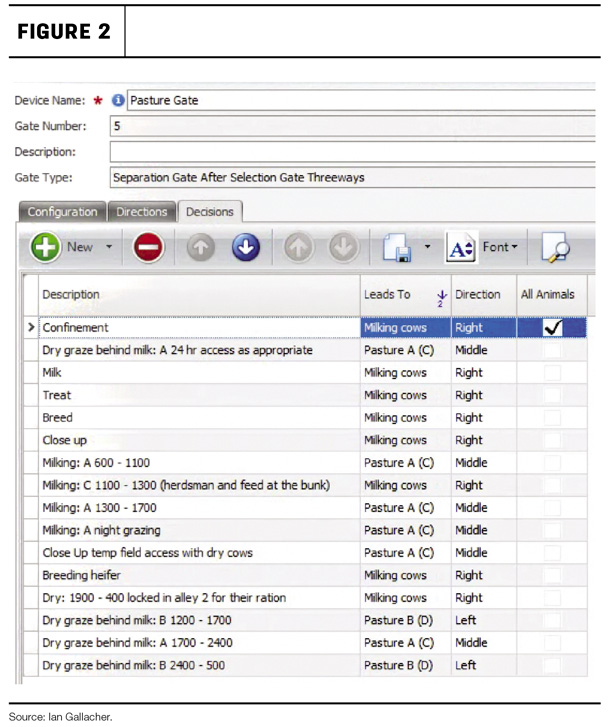

Figure 2 shows some of the rules we set on the pasture gate this year to determine when cows of various groups can access different paddocks on the farm or need to return to the barn to milk before going to graze.

For example, we can route dry cows to the west paddocks from 5 a.m. through 11 a.m. while milk cows go to the east paddocks during that same time.

The eastside paddocks are essentially the mirror of the westside paddocks. Let’s focus on the westside paddocks now. A cow walks to the pasture gate, her tag is read, the rules are applied and she’s routed to the middle lane, which then opens to the westside grazing lane.

The grazing lanes are 15-feet wide and have dirt footing. Cows will walk the grazing lane more in this system than if they were locked in a paddock for several hours. Footing is important, and dirt is gentle on their feet. Our soil and cow numbers we have work well with this.

The grazing lanes east to west are enclosed by hotwire. The hotwire circuit needs to be up and there needs to be a good zap to it. We’ve found it takes about two days for cows to start leaking out of paddocks once the circuit is down. Our grazing lanes are separated east to west by a single strand of hotwire with 15-foot-wide hotwire gate openings every 60 feet on the paddock side of each grazing lane. Photo 2 shows an open spring-handle gate that we hook onto the hotwire, separating the east and west grazing lanes.

The cow walks, sees the hotwire and turns into the open paddock.

Within the west field, we have 28 of those paddock openings and we string out a hotwire reel from the north post of the gate opening to the field fence 525 feet west of it. 60 feet south of that we do the same thing to create a paddock that is 60 feet by 525 feet long.

The gate opening is always on the barn side of the paddock so that cows can walk straight back to the barn. This setup allows us to cross fence a paddock with a single 60-foot strand of hotwire with spring handles on it, or to make paddocks 60 feet, 120 feet or 180 feet wide or whatever forage and cow intake require. Our K-Line irrigation runs under it all, and when it’s time to move in with a tractor or equipment, nothing is in our way.

Our grazing lanes are free flow. Cows walk back and forth in a lane and in and out of paddocks when they want to. The first year, we saw cows move in groups to and from paddocks; the second year it was individual movement. Cows find safety in numbers, so it was really good to see an individual cow walking calmly to pasture or back to the barn. This showed us that the system was low stress and promoted happy cows. They can meet their needs in the barn or in the fields for food, water and a place to ruminate whenever they choose to do so.

Motivating cow movement from field to barn

Food and water are carrots that motivate cows to make trips to the barn.

Cows move first for food. In the spring, the forage we have in our grazing paddocks booms. Here we see the winter annual components of the mix are growing rapidly in the cool and warming spring soils. Consequentially, if we let the cows mob into a paddock in the spring without cross fencing, they’re going to trample a lot of that feed. That feed will then stay long, and by the next time we come to graze it, quality will have dropped. And if a cow gets a full belly, she’ll lay down to ruminate. By cross fencing and giving cows smaller breaks of grass, we can keep the cows moving to milk.

Cows move next for water, especially in the heat of summer. In fact, studies show that a cow will get up and drink nine times a day in a barn. That creates opportunities to milk. If a cow is thirsty, she’s going to move to the barn from the paddocks to look for water, unless she has her needs met from a sprinkler head, as often happens here despite shut-off valves on each K-Line pod.

Cows are smart. Our cows are never more than half a mile from the barn. And on really hot days, we’ll modify the pasture gate rules to keep them in during the heat and let them out at night. If your paddock layout puts cows a long way from water, I would suggest putting water partway back to the barn to encourage them back without running them dry.

Don’t cripple your plants; don’t starve your cows

To move cows just by running a paddock low on feed won’t be enough to bring them all in. You’ll need to really run it out, and that’s hard on plant regrowth, which hurts production of needed milk-quality forage.

Unless you want to really keep cows on the edge of hunger or thirst and deal with the ramifications of those, you’re going to need to meet, or come close to meeting, the cows’ needs for food, water and a place to ruminate in the paddock.

But if cows’ needs are met in the paddock, only fetching will move them back to the barn to milk three times a day.

Finding a balance between how tight to graze versus how much to fetch cows takes time and varies over the season on your farm with your irrigation, plants, soil, and management and production goals.

This year, we decided to fetch twice a day. Our cows kept their condition, our milk yields stayed up and our milk-quality forage management went pretty well. Thanks be to God.

At 6 a.m. cows had access to a new paddock. In the spring it was cross fenced and a quarter to half the size of a paddock in the summer. Stocking density was high in the spring, but feed was abundant and our goal was to have the cows take it pretty tight so that when they came back some days later for the next grazing, the forage was uniform and vegetative. I’m being vague about how many days later because on our farm that’s not a set number. It’s what we see in the fields that guides where and when we do milk cow grazing, dry cow follow up or machine harvesting. We’ve found that we don’t need to apply any manure until late June or early July. Prior to that time, high stocking density and good cow movement helps to trample their leavings into the soil.

At 11 a.m. we would feed at the bunk, turn off the alley scrapers, and set the headlocks to do breeding and other herd work. The cows got used to this and would start to meander up. By the time we had everything set up, if they weren’t in we’d go flush them out of the paddock and up to the barn. We had pasture gate permission set to turn milk cows back to the barn for two hours. During that time, we would do herd work, set fence and open up their afternoon paddock.

With that afternoon paddock, the same principles applied. This time we’d bring them in at 6 p.m., then let them back out to another paddock for evening. We’d limit feed in that evening paddock so they would come up to the barn sometime in the early morning and milk before going out again to the 6 a.m. paddock.

In summer, we’d do the same thing but give larger paddock allocations. Toward the end of the grazing season we were giving the milk cow group as much as three paddock widths per grazing.

Throughout the season, dry cows would graze behind milk cows and we’d vary paddock size for them based on their numbers and available feed and our forage residual management goals. We graze our heifers in separate fields in their own paddocks.

God willing, this series of articles has shown you principles and practices of robotic milking while grazing that can be adapted to your farm and needs. God bless you.

Ian Gallacher worked in software design and management for 18 years. In 2015, he and his wife, Margaret, started to build Lord’s Bounty Farm in Jefferson, Oregon, and its automated dairy from the ground up, to the glory of God. Email Ian Gallacher.

PHOTOS: Photos provided by Ian Gallacher.