We have been discussing the optimum use, management and design of footbaths for about 20 years, but what evidence do we have that footbaths are effective in controlling digital dermatitis (DD)? Let’s take a quick look at the research, management challenges and novel ways to assess its success.

First, the data

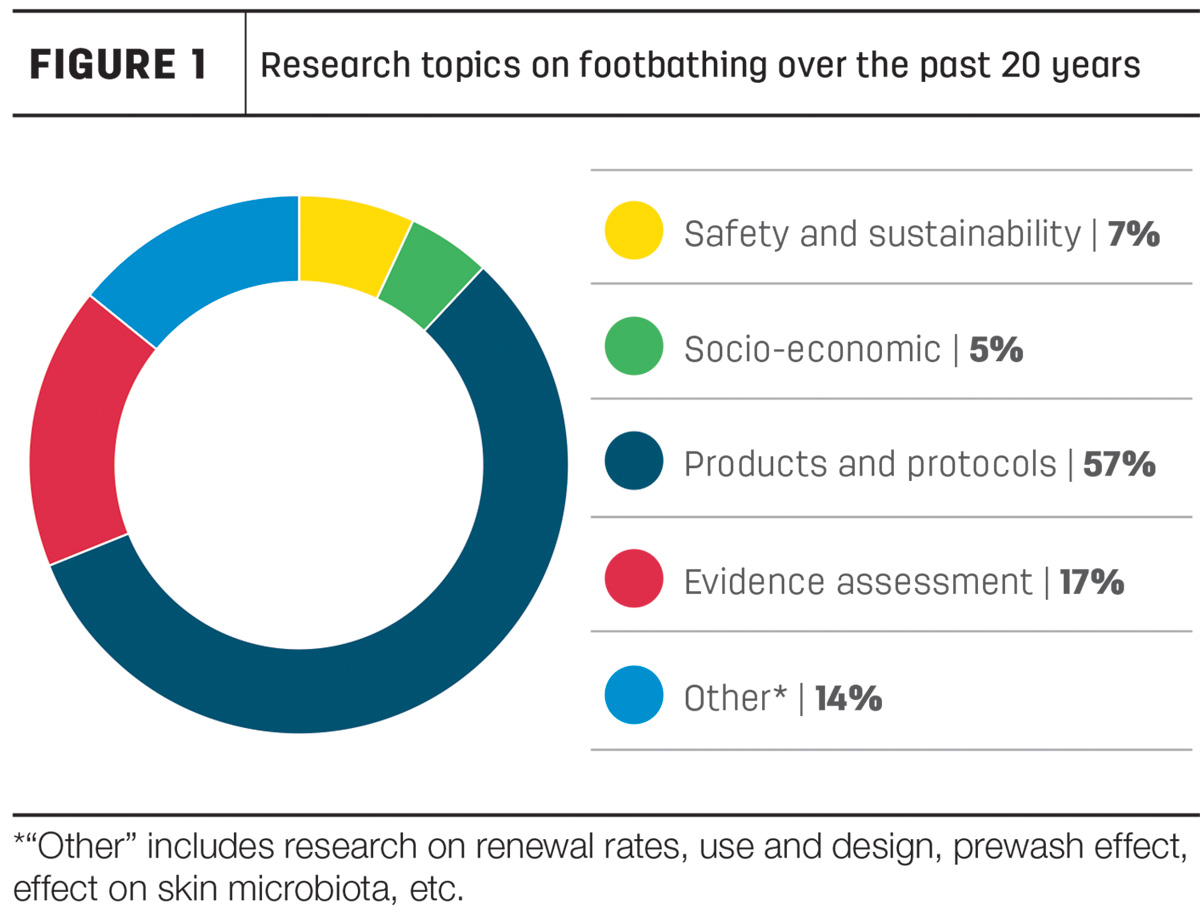

Since 2000, there have been approximately 45 peer-reviewed publications focused on footbathing (Figure 1). Most (70%) of the research comes from western Europe and the rest from Canada and the U.S. Different countries have different farming conditions in terms of housing systems, herd sizes, hygiene, DD prevalence, available or approved footbath products, and even differences in terms of economic resources that impact the methodology of a footbath trial.

We can expect that these differences impact results to some extent. A variety of topics have been investigated, including product renewal rates, use and design of baths, prewash effects, impact of products on human health, safety and environment, their cost-benefit and more. But the majority (about 60%) of studies on footbathing have focused on clinical trials that compared two to four products or protocols.

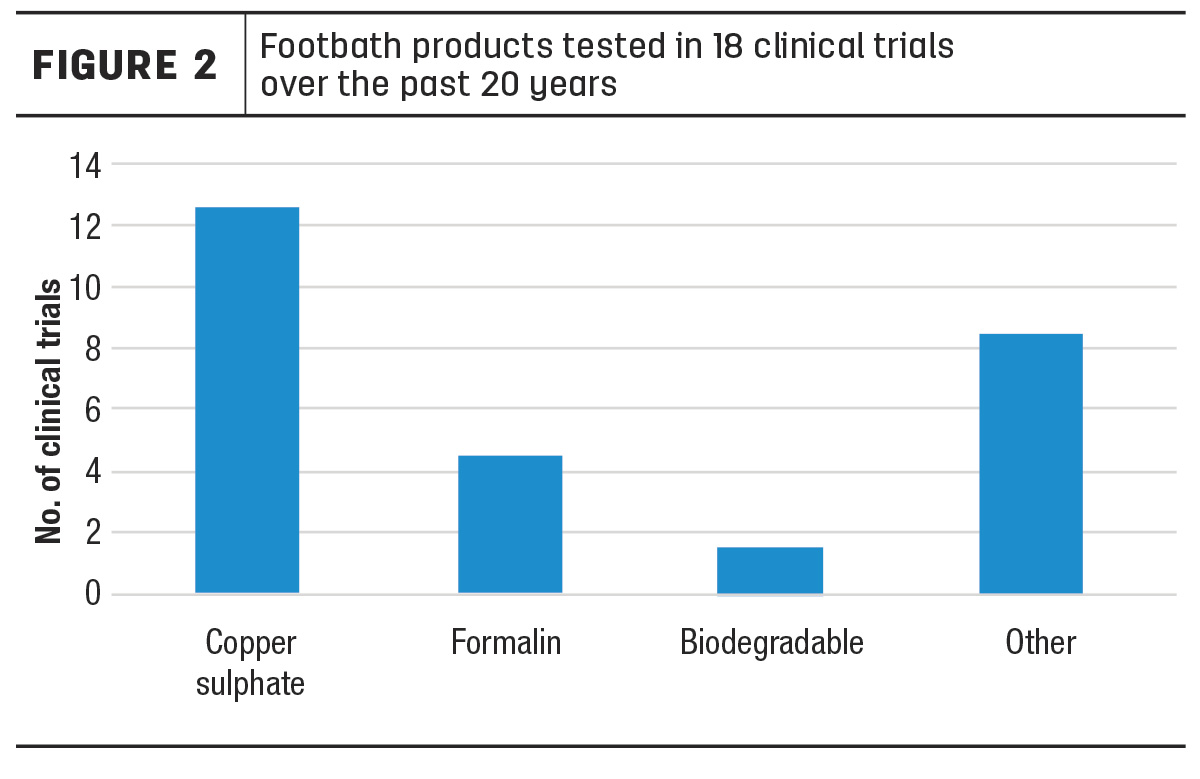

Approximately 25 unique footbath products have been tested over time in those clinical trials (Figure 2). The numerous products tested in published clinical trials does not come close to the plethora of products available on the market, most of which claim to be 100% effective and safe.

However, very few of these product tests have yielded solid scientific evidence supporting these claims. The abundance of footbath products on the market often prevents people from thoughtfully choosing a product to avoid the hassle of wading through options. In addition, it often leads to constant product switching depending on availability, price or trendiness. This adds an extra layer of difficulty when trying to effectively implement and evaluate footbathing practices.

Fortunately, in the footbath literature, a Canadian and a French study evaluated the evidence from multiple scientific studies on the efficacy of footbathing in controlling DD. These studies are formally called meta-analyses; they rank at the top in the hierarchy of evidence and use statistical techniques to assess the combined results of many studies at once.

Here are three take-home messages from these meta-analyses.

The evidence behind using copper sulphate is not as strong as you might think

Despite the wide use of copper sulphate footbaths, very few robust clinical studies confirm their effectiveness. Among all footbath products and protocols tested, 5% copper sulphate used at least four times per week is the protocol with the strongest evidence of efficacy when compared to no footbath or water only. However, let’s keep in mind, it is also the product that has been tested the most (used in 14 out of 18 clinical trials that compared disinfecting products). This does not necessarily mean other footbath products do not perform well – rather, other products have not been tested as rigorously as copper sulphate. It is known copper sulphate works and has historically been the go-to footbath product for research and on-farm use, but that does not mean it should continue being in the future, which leads to the next point.

More emphasis should be placed on biodegradable footbath products

Only three out of 18 clinical trials tested biodegradable footbath products. This is surprisingly low considering the commitment of the dairy industry toward sustainable, environmentally friendly practices. The ban of copper sulphate in the European Union, our country’s net zero emission goals, along with consumer demands for sustainability, give us a taste of the challenges facing the dairy industry. Challenges that are and will be shaping regulations of what goes into manure systems and into the soil. From a research and market perspective, there needs to be a shift toward developing and properly testing footbath products that meet health and safety standards for the environment, people and livestock. Added to that, it is crucial to implement practices that improve foot hygiene, as this is the most important factor influencing the occurrence of DD lesions.

A plea to test the effectiveness of footbaths in a more consistent way

“Are footbaths effective in controlling DD?” This was the core question the Canadian and French meta-analyses tried to answer by evaluating the published literature. As it turns out, the tremendous variability among clinical trials in terms of study design and protocols tested has weakened the evidence supporting footbathing. For example, most (60%) clinical trials based their result on one herd and some (20%) on fewer than five herds; several trials used inappropriate footbath design (too short, too shallow); the duration of most trials was too short (less than 13 weeks) to properly assess the occurrence of new DD lesions; and trials had different definitions of success (for some, success was the absence of new lesions, and for others success was “not getting worse” or “healing”). This variation of study design results limited the statistical ability to detect differences among products and protocols.

Does this mean footbaths are not effective and, therefore, there is no point in using one? No. This is one of those rare cases when anecdotal evidence beats scientific evidence. Overall, the industry must be more rigorous when testing footbath products and protocols to strengthen the evidence and support more meaningful conclusions.

Now, leave aside the challenges from research studies. Most of us who are hands-on developing, implementing and managing footbath practices know footbaths work if used properly. We have good guidelines on the who, what, when and how of footbathing. We still need to work toward answering the why: Why are there so many barriers toward the implementation of footbath practices that we know work? The proper use of footbathing is often perceived as labour-intensive, time-consuming, costly and somewhat difficult.

What is one thing we should be mastering in footbath management?

Consistency. Most of the time, effectiveness is not about the product or the protocol; it is about a consistent routine. The perceived barriers to improving footbath management are numerous. One of the simplest ways to make this easier is through automation.

In 2014, a study from the University of Calgary was developed to assess the effect of an optimal footbath design and protocol using an automated footbath. The aim of automation was to eliminate human error, to consistently achieve a correct chemical concentration and to consistently ensure an accurate frequency and interval of use. Nine herds joined and remained in the study over 22 weeks. At the end of the trial, there was clear and strong evidence that the automated system, along with the protocol, successfully reduced active DD lesions on six of the nine herds, with the three remaining herds maintaining a low active DD prevalence.

Eight years later: What do producers say about their automated footbaths?

All nine participating herds are still using the automated footbath with very few changes to the protocol or design. Also, they all reported having DD under control (which was later confirmed with hoof-trimming records). Some minor maintenance issues related to product buildup, calibration, functioning of the dispenser and of the flush door were noted. The main reasons why they continue using the same automated footbath and nearly the same protocol were related to consistency, ease, low maintenance, high return, no need of retraining employees or supervising and no need to handle the product. The automation of the footbath enabled a consistent routine, successful DD control and, most importantly, producers’ satisfaction.

Practical thoughts for the future

Producers’ feedback on the effectiveness and long-term performance of the automated footbath was very positive, but one thing stood out. In eight years, all herds made no changes or very little changes to the footbath protocol. A consistent routine is key, but when a sustained low level of DD is maintained in an endemically infected herd, we can customize the footbath strategy to increase efficiency and decrease the economic and environmental impact. In addition, we would expect that a herd’s DD level would be impacted over time by seasonality, management factors and by the dynamic nature of the disease. The fact that the footbath protocol implemented in the 2014 trial has remained static in most farms could be because there is no routine detection of the disease. Or it could be that DD is being detected regularly, but no one is using this information to make decisions at the herd level to customize the footbathing strategy. Either way, an approach is needed that lessens the overwhelming to-do list for dairy producers while allowing for optimized DD control plans that alleviate the animal welfare concerns.

To ensure efficient use of footbaths, we need an integrative approach to technology; development of sustainable chemicals; automated control of footbaths; DD prediction tools through herd testing; the use of artificial intelligence for automated, real-time DD detection; and integrated decision-making systems.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.