June 2022 “mailbox” prices averaged about $1.03 per hundredweight (cwt) less than announced average “all-milk” prices for the same month, based on a preliminary look at two USDA milk price announcements. Marketing deductions to cover higher processing costs could drive the price spread even wider.

First, some numbers:

- During June, U.S. all-milk prices averaged $26.90 per cwt, down 40 cents from May 2022 but $8.50 more than June 2021.

- The June 2022 mailbox prices for selected Federal Milk Marketing Orders (FMMOs) averaged $25.87 per cwt, down 45 cents per cwt from May 2022 but $8.34 more than June 2021.

At $1.03, the difference in the average all-milk and mailbox prices in June is the widest in 2022, up from $1.01 in March. It’s also the widest spread since October 2021, when the gap was $1.16 per cwt.

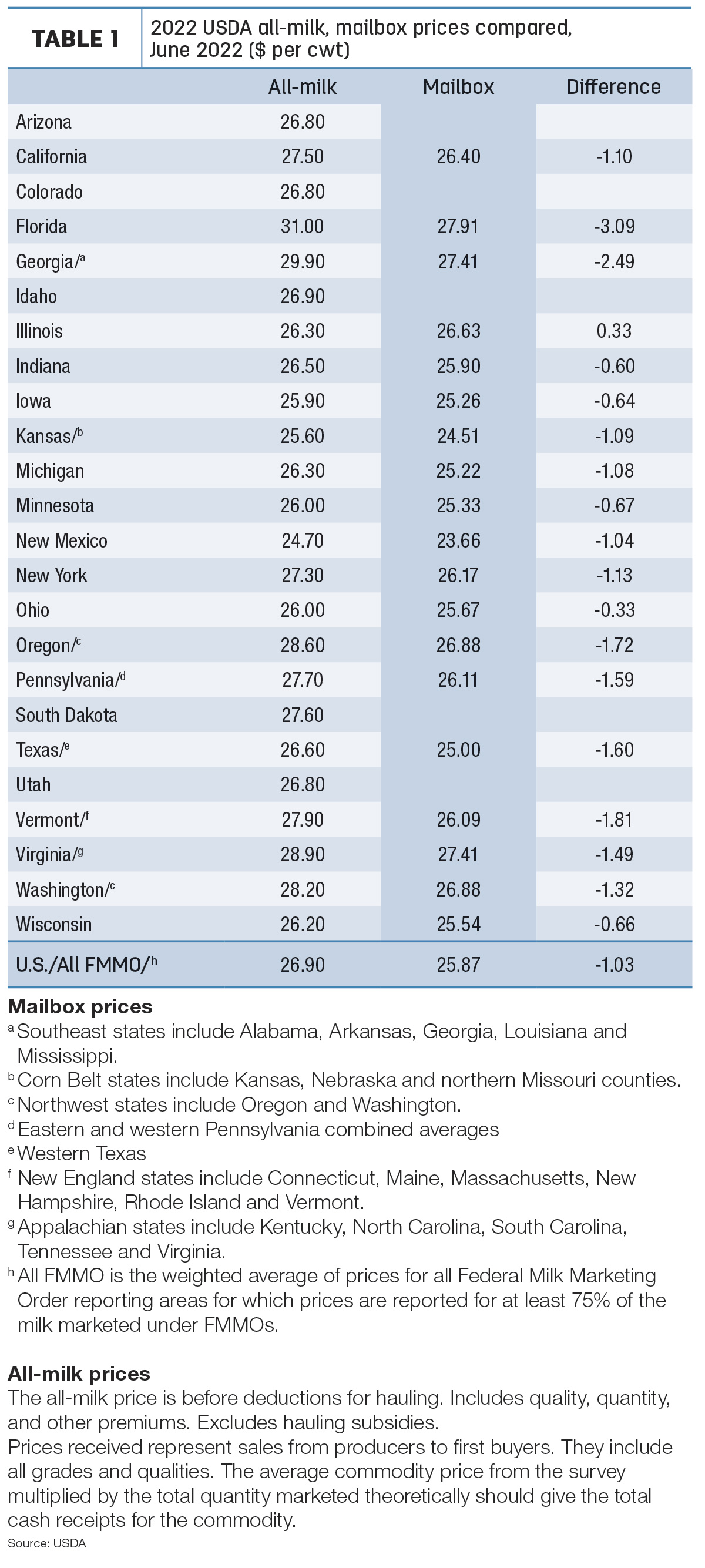

In Table 1, Progressive Dairy attempts to align the state-level all-milk prices and the FMMO marketing area prices as closely as possible. The June spread between individual states or regions varied widely, with a difference of -$3.09 per cwt in Florida to a +33 cents per cwt in Illinois.

The difference in the two announced prices can affect dairy risk management, since indemnity payments under the Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC), Dairy Revenue Protection (Dairy-RP) and Livestock Gross Margin for Dairy (LGM-Dairy) programs are all based on the all-milk price.

Higher deductions announced

Impacts of higher processing costs could drive the spread between all-milk and mailbox prices wider. According to the American Dairy Coalition (ADC), some Wisconsin producers have received notices that milk check deductions, ranging between 90 cents and $2.50 per cwt, will be implemented on September milk marketings and continue through the end of the year.

In late September, leaders of Midwest dairy cooperative Foremost Farms notified its producer milk suppliers it would implement market adjustment deductions of 90 cents per cwt, beginning with September milk marketings. In a letter to producers, Greg Schlafer, president and CEO, and Darin Hanson, senior vice president of supply chain and risk management, said the deductions were needed to address record-high labor costs at manufacturing facilities, higher costs for energy, packaging, equipment and quality services, and significant differences between Class III milk costs and revenue generated from the co-ops cheese and whey product sales.

“Extreme inflationary pressures make it necessary for Foremost Farms to adjust milk pricing through a market adjustment to ensure continued viability of the business,” they wrote. “Federal order milk pricing formulas, which include make allowances, have not been adjusted since 2009. The make allowance is a cost factor built into the milk price to account for all the costs required to convert milk to the final product. These costs have increased significantly over the past year.”

ADC founder and CEO Laurie Fischer said a recent cost of processing study indicates that the current make allowances already built into the USDA end-product pricing formulas are collectively about $1per cwt short of covering costs to make bulk cheddar, butter, nonfat dry milk and whey products that are surveyed monthly for the USDA pricing formulas.

“These milk check deductions appear to be a way to shift rising costs over to farmers through mailbox milk check deductions,” Fischer said.

In an email statement to Progressive Dairy, Foremost Farms said the co-op’s field representatives and leadership were responding directly to co-op members to answer specific questions.

“Decisions to adjust pay price are difficult and only implemented to ensure the long-term viability of the cooperative,” Foremost Farms’ Schlafer and Hanson wrote. “We value your support and the high-quality milk you supply to the cooperative,” they concluded.

Make allowances are part of the ongoing discussion regarding potential FMMO reforms. Citing Class I milk pricing formula changes made in the 2018 Farm Bill, ADC recommends any make allowance formula changes be part of a formal FMMO hearing process.

“We believe these 'processor make allowances' that are embedded in the pricing formulas should be put on hold until the milk pricing change that was made in the last farm bill is thoroughly vetted through a side-by-side comparison at a FMMO hearing, or is reversed,” Fischer said. “The reason we have taken this position is because farmers are already on the short end of the stick. They are the last rung in the supply chain ladder, and they have no one to go back to, [to] extract a make allowance for their rising inflationary costs.

“If the make allowances are elevated without addressing these other concerns, the mailbox price will be reduced to the farmer, and there is nothing to prevent processors from reblending and the potential for additional deductions,” Fischer said.

Some disclaimers

All-milk prices are reported monthly by the USDA National Ag Statistics Service (NASS). Mailbox prices are reported monthly by the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) and generally lag all-milk price announcements by a month or more. As Progressive Dairy notes each month, there are disclaimers when comparing the two price announcements:

- The all-milk price is the estimated gross milk price received by dairy producers for all grades and qualities of milk sold to first buyers, before marketing costs and other deductions. The price includes quality, quantity and other premiums, but hauling subsidies are excluded.

- The mailbox price is the estimated net price received by producers for milk, including all payments received for milk sold and deducting costs associated with marketing. Based on latest annual data, about 61% of U.S. milk production was marketed through FMMOs in 2021.

Data included in all payments for milk sold are over-order premiums; quality, component, breed and volume premiums; payouts from state-run over-order pricing pools; payments from superpool organizations or marketing agencies in common; payouts from programs offering seasonal production bonuses; and monthly distributions of cooperative earnings. Annual distributions of cooperative profits/earnings or equity repayments are not included.

Included in mailbox price costs associated with marketing milk are hauling charges; cooperative dues, assessments, equity deductions/capital retains and reblends; the FMMO deduction for marketing services; and federally mandated assessments such as the dairy checkoff and budget sequestration deductions.

Geographies may differ

The price announcements also reflect similar – but not exactly the same – geographic areas. The NASS reports monthly average all-milk prices for the 24 major dairy states. The mailbox prices reported by the USDA’s AMS cover selected FMMO marketing areas.

For example, while NASS reports an all-milk price for Georgia, the mailbox price lumps Georgia with other Southeast states: Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi. Similarly, Kansas is part of the Corn Belt states, Oregon and Washington are combined in the Northwest states, Vermont is among six New England states, and Virginia is clustered with Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee among Appalachian states.