Why should a 21st-century dairy farmer have to approach his business as if he’s still in the 20th century? Agriculture remains the least-digitized industry, says the McKinsey Global Institute.

The U.S. agricultural market has reached less than 10 percent of its digital potential, McKinsey estimates – and it’s an industry that stands to benefit most from the digital revolution.

Take a quick background check:

1. USDA census data puts the average U.S. farmer at slightly over 58 years old.

2. He (men outnumber women farmers by 6 to 1) has a minimal workforce, with additional labor from family members or a foreign-born workforce.

3. The average U.S. dairy farmer faces a raft of challenges negotiating low prices and dwindling margins.

Farmers are largely price-takers, selling their milk at commodity prices unless they can boost margins through direct milk sales, added value or farm processing. Milk consumption is slowing, and the global dominance of the U.S. dairy industry is declining as new production centers emerge. So their approach to their business is having to change to reflect these factors.

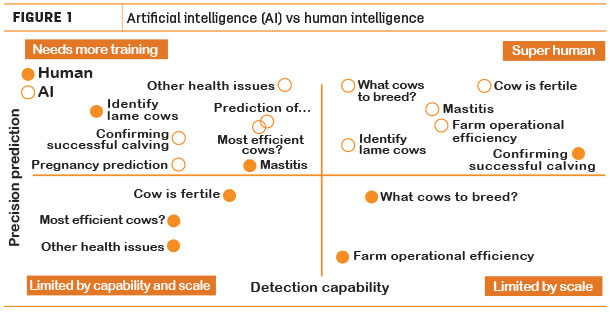

Our specialization is artificial intelligence and machine-learning. We used these disciplines to create Ida, the first artificial intelligence assistant for dairy farmers. But that’s not because we believe farmers need more data; we believe they need more actionable insights to help them adapt to these challenges and build their businesses.

We’ve a few examples to share.

Measuring farm efficiency

Ever since humans started keeping cows for their milk, farmers noticed some cows yielded more than others. With more milk, they generated more income – yet they consumed a similar amount in feed.

Production efficiency is the holy grail of dairying. We’re concerned not only with the cool, hard dollars and cents of dairy production but also the less tangible effects of large-scale farming on resource use. We need to know which cows produce the most milk for least input. We also need to accurately offset other costs, such as veterinary interventions.

Most farms have that data available. The parlor monitors each cow’s production. Farm management software keeps track of which cows regularly demand the veterinarian’s attention. But with the machine learning of Ida, we can bring this together effortlessly and to great effect. Artificial intelligence identifies patterns, trends and correlations, making suggestions that take the hard work out of decision-making and the quest for production efficiency.

Saving on farm costs and time …

Every action, every job, comes at a cost. What if we could save time doing one task, earning “credit” to invest in another?

Our technology uses a biometric sensor for each cow, collecting data that feeds into the same artificial intelligence. Now we’re alerted to subclinical symptoms that might otherwise be undetectable.

In other industries, deploying artificial intelligence like this is “predictive maintenance.” Take a factory’s machines. Diagnostics identify when a bearing needs repacking, or a seal replacing, suggesting action before the part fails. By extending those same principles to cattle health – mastitis, for example – we are alerted before problems become serious. Prevention is better than cure.

Many farmers can’t reduce their workforce further, yet they have no fewer tasks to complete. Artificial intelligence is perfectly placed to tackle some of those tasks – heat and estrus monitoring or an imminent calver, for example. Rather than waiting for something to happen, the farmer can re-invest that time more usefully elsewhere.

Consider, too, how combining artificial intelligence and machine learning can improve a farm’s capital efficiency. With each production animal representing a unit of capital, Ida allows accurate, consistent selection of “efficient” units.

Meanwhile, welfare-friendly milk, or milk from farms with low-intervention protocols, provide the attraction of added value for processors attuned to the consumer’s shifting tastes and concerns.

… and boosting animal welfare

Nearly 60 percent of U.S. consumers say animal welfare is important in food production, says a 2017 report from market researchers Packaged Facts.

Farmers are often shown in a bad light on animal welfare, yet most farmers care deeply about their animals, developing a conscientious approach toward their well-being, comfort and health. That’s why time isn’t the only beneficiary from deploying a digital dairy assistant. Healthy, happy cows produce more milk.

Releasing the farmer from his duty of physically inspecting each animal for signs of illness or ill thrift frees up time for other activities. But artificial intelligence’s ability to spot those early signs also allows animals to be treated sooner. That’s a great story to take to the consumer.

Breaking down barriers, optimizing workforces

Application of artificial intelligence and associated technologies isn’t only about displacing labor. The success of the U.S. agricultural industry depends heavily on an estimated 3 million agricultural workers who provide an essential labor resource without which many farms could not function.

National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) figures suggest the majority (73 percent) are foreign-born. Might language and communication be a challenge? Further NAWS figures give us an indication: Only 31 percent of all farmworkers in the survey claimed to have a “good” grasp of English. More than a quarter said they spoke no English “at all.”

Good communication with a workforce is essential, not only for efficiency but also for morale, worker productivity and safety. To be most useful, artificial intelligence must be able to speak any language, not just English. This is especially important given the technical nature of dairy farming.

Confident about explaining a hoof lesion to a Spanish-speaker? Or that the cow who’s about to calve had two earlier difficult deliveries? Our artificial intelligence understands this kind of data irrespective of the language – and presents it in a language you, or your workers, will comprehend.

Still on the subject of workforces, what’s the best way to optimize yours? It’s important your workforce is confident in their communications with one another but, given that your hired help is likely to be temporary rather than permanent, could technology also help elevate their knowledge and skills?

Our friends at McKinsey again provide us with a better insight here, for their report identified the importance of people re-skilling to work with machines rather than competing against them (a battle they’ll probably lose).

Technology allows a workforce to get up and running more quickly – an app that controls a machine is more intuitive for a worker to learn – in the same way technology helps us identify the blind spots better done by machines.

Conclusion

Outside agriculture, debate has focused on how the rise of artificial intelligence might displace humans from the workforce. After all, artificial intelligence doesn’t need to sleep and isn’t subject to labor or wage regulations.

But on the farm, we see technology from a different perspective. It’s not here to eliminate the human role. Instead, we’re developing its role as an assistant to the human, elevating the role of the human on the farm. Ultimately, it’s helping to provide more food of better quality and healthier than it would be without technology, produced by a happier, healthier and more profitable farmer.