Within the last few years, we’ve taken a more critical look at the relationship between forage fiber particle size and forage digestibility. Researchers at the Miner Institute in New York have explored the concept of reducing particle size of forages with lower fiber digestibility to improve animal performance.

They evaluated dramatically reducing the particle size of timothy hay in the diet. Before we discuss the project outcomes, let’s review some basic forage vocabulary to better understand these research findings.

Key terms to understand forage digestion

Both forage particle size and digestibility influence the passage rate of forage from the rumen. Forage passage rate is a paradox. Forages that pass faster help drive dry matter intake (DMI). Forages that pass slower or, in effect, are retained in the rumen longer, have greater digestibility. As a result, we need forage passage rates that are not too slow, nor too fast, to optimize total nutrient digestibility of forages.

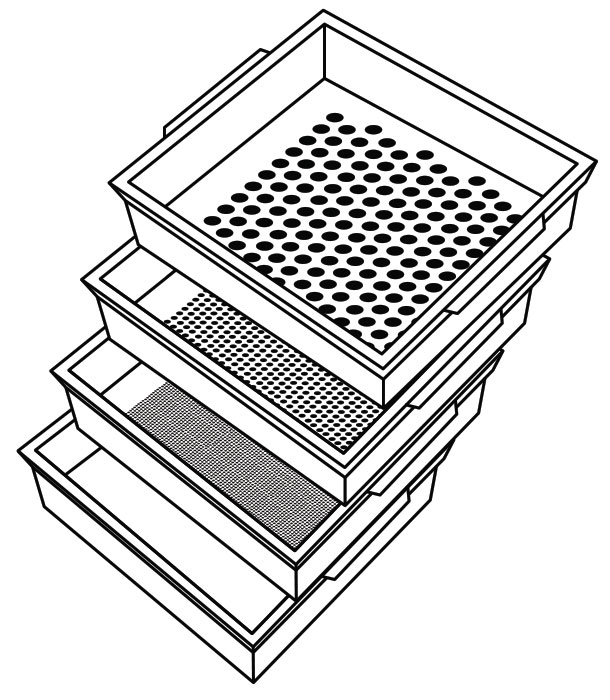

One of the simple measurements used to characterize forage fiber is the particle size of physically effective neutral detergent fiber (peNDF), which is the fraction of forage particles retained on the 4-millimeter sieve and greater when using the Penn State Particle Separator (PSPS). This is the portion of NDF that stimulates rumination.

The second measurement to characterize forage fiber is undigested NDF. This is an in vitro lab measurement of the amount of forage NDF impossible for rumen bacteria to digest. Undigested NDF after 240 hours of fermentation (uNDF240) is the primary fiber digestibility measurement currently used to characterize forages and diets. The fiber residue remaining after 240 hours of in vitro fermentation cannot be degraded by rumen bacteria; thus, it is not utilized by the cow and is deemed indigestible.

Research results of reducing forage particle size

Now let’s apply this background information to recent research conducted at the Miner Institute. One of the key findings was that, when diets contained greater levels of uNDF240, reducing the peNDF of one of the forages in that diet resulted in increased passage rates, allowing for greater intakes. However, there are important considerations prior to implementing such a strategy on-farm.

Staff illustration,

First, the Miner Institute research was only able to explore this concept with diets containing corn silage and dry timothy hay. In fact, the timothy hay was the only ingredient to have its particle size altered in these experiments to adjust peNDF supply in the treatments. The results indicate that shortening forage particle size in diets with greater uNDF240 has the potential to increase DMI, but the type of forage may dictate the degree of size reduction needed.

The reason for this clarification is: Grasses (such as timothy) and legumes have very different ruminal dynamics. Michigan State University researchers compared forage passage rates as well as the rumen dynamics of alfalfa silage and orchardgrass silage, and found that diets containing the orchardgrass silage had significantly slower passage rate for smaller fiber particles. They found that more than 55% of the particles within the rumen were less than 2.36 millimeters for both silages, indicating that particle size was most likely not the sole limiting factor of passage.

They attributed this difference in passage to the selective retention of grass forage particles. This means that the physical form of grass forages has a great effect on rumen retention time. The thought process here is: Grass forages spend more time in the rumen because the rope-like nature of grass leaves entangle in the rumen mat to a greater degree than alfalfa. Because of this research, the particle size reduction of alfalfa may not need to be to the same degree as grass in order to gain the same benefit. A more moderate and conservative approach appears to be more beneficial.

While our focus so far has been on timothy and alfalfa, it is important to note corn silage because it generally makes up a significant portion of dairy diets. It is critical to understand that the NDF fractions of corn silage (C4 grass) do differ from C3 grasses (timothy) and will result in some differences in animal responses. But corn silage will exhibit ruminal dynamics similar to timothy, when compared to alfalfa, due to its physical form. Understanding this, we can anticipate an increase in DMI as the result of moderately reducing the particle size of corn silage.

Because particle size reduction research is still relatively new, it is difficult to provide exact recommendations for legume and corn silage particle size reduction based on uNDF240, but data do suggest that reducing grass particle size may improve DMI. By no means is this a green light to pulverize forage particle size in the hopes of gaining maximum intake. This can result in forage fiber that passes too fast and a reduction of utilization within the cow.

With a continual focus on forage quality, it goes without saying that constant monitoring of particle size entering silos from the field is needed. The ideal theoretical length of cut will vary due to chopper knife sharpness and cutter bar integrity, varying from farm to farm. Hopefully, in the near future, a trial will be conducted evaluating peNDF and uNDF240 with corn silage and alfalfa as the primary forages.