Infectious lesions are those disrupting the foot skin, with common examples including digital dermatitis (DD), interdigital dermatitis, heel horn erosion and foot rot. Non-infectious lesions disrupt horn growth and include white-line lesions, sole hemorrhage, sole and toe ulcers, among others.

Sole ulcers, white-line lesions and DD are the most common lesions and are considered painful. The aim of this article is to determine associations between the presence of hoof lesions and lameness in Alberta dairy cows. Specifically, it addresses the question: What is the relationship between having a painful lesion and a cow being lame? We expect better understanding of these associations will improve lesion detection and ultimately reduce lameness.

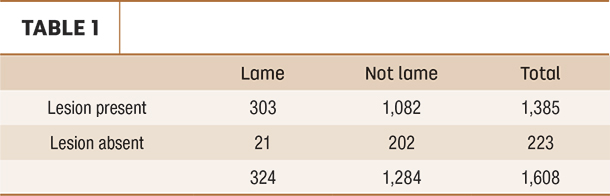

The data analyzed for this article was collected from 10 farms in 2013 to 2014 by the University of Calgary lameness team. All cows were locomotion scored and, one day later, all cows’ feet were inspected in a trimming chute with the assistance of a hoof trimmer. A lame cow was defined as having an obvious limp or head bob. Cows with any infectious or non-infectious lesion were recorded as “lesion present,” and cows without a lesion were recorded as “lesion absent” (Table 1).

On average, 20% of cows were lame. Of all lame cows, 94% had a lesion present. Something that stood out was: 84% of cows that were not lame also had a lesion present. A cow with a lesion was almost three times more likely to be lame than a cow without a lesion. However, there were many cows with a lesion that were not lame and, therefore, unlikely to be trimmed or treated if the herd is not subject to a whole or routine herd trim.

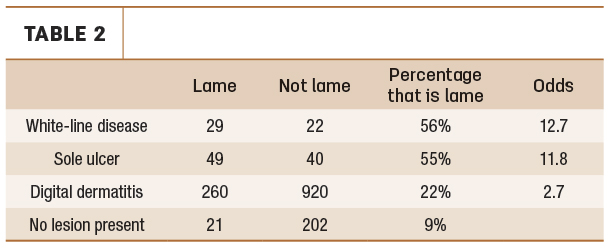

The presence of a painful lesion such as a sole ulcer, white-line lesion or DD, and their impact on the likelihood of a cow being lame, was also determined (Table 2).

For example, 56% of cows with a white-line lesion and 55% of cows with a sole ulcer were lame. However, only 22% of cows with DD were lame. Our results suggest a cow with a sole ulcer or a white-line lesion is 12 to 13 times more likely to be identified as lame, whereas a cow with DD is three times more likely to be identified as lame. In general, a white-line lesion or sole ulcer causes more pain than DD; then it is more likely to result in “obvious” lameness and become easier to identify. However, we conclude identifying lame cows as a method to determine lesion presence is not very accurate.

Hoof trimming is currently used to improve hoof health by identifying, preventing and treating hoof lesions. There are large variations among farms regarding the frequency hoof trimming is scheduled, and emergency hoof trimming should be done for cows that are mild or severely lame.

Ideally, cows should be identified and treated soon after developing a lesion. However, monitoring lameness is time-consuming and is often not done regularly. In our study, 84% of non-lame cows had a lesion present, putting them at higher risk for becoming lame.

It is important to keep in mind: Not only lame cows require frequent trimming but also cows that do not appear lame. Automated methods for detecting lameness as a result of hoof lesions can help reduce lameness in the herd. Technologies include weight distribution systems, image processing and wearable sensors. However, these technologies are costly and require further advancements to increase accuracy and precision of detecting abnormalities in cow gait or posture.

Although there is an association between the presence of hoof lesions and lameness, this relationship is far from “perfect.” The type of hoof lesion influences lameness prevalence differently. Cows with a sole ulcer or white-line lesion have a greater chance of being identified as lame than those with DD. Prevention methods should be targeted at identifying and monitoring hoof lesions and providing treatment as needed. Although a cow may not show signs of lameness, producers can benefit from increasing efforts to identify cows with lesions, as that will reduce the lameness prevalence in the herd. ![]()

Makaela Douglas is a Ph.D. student at the University of Calgary. Laura Solano is an independent farm animal care consultant. Karin Orsel is a veterinarian with the University of Calgary.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.