“I am trained as a natural scientist,” Marina von Keyserlingk, professor at the University of British Columbia, said. “But the more time that I’ve been working in animal welfare, I have been humbled because I don’t think I can do animal welfare research well if I don’t understand the people that are involved in all of this.

Animal welfare science is a socially mandated science. It’s where people and animals come together.”

Animal welfare has two sides to it, she said. There are the animals we care for, but there are also the people who are involved. The people are the farmers, veterinarians and the public.

While there is a portion of the public who will never be satisfied with our animal welfare standard no matter what we do, these “animal activists,” as we often call them, only represent a fraction of the public. In her presentation at the 2016 Western Canadian Dairy Seminar, von Keyserlingk focused on the rest of the public – the majority – and their concerns about the modern dairy farm.

It is important to differentiate among the public, consumers and citizens. The word “public” is often used as a catchall term to describe everyone who is not associated with the dairy industry. However, it is not that simple, she said. “Citizen” refers to the role a person plays when they are outside of the grocery store.

Here they often take the time to reflect on things before making a decision, such as when voting. The “consumer” refers to the person’s buying behavior in the grocery store.

It is well established that consumers usually make buying decisions based on price. But when von Keyserlingk and her colleagues have a conversation with them outside of the store, people often tell them that they would be willing to pay more based on other factors.

It is here that the conversation is no longer with a consumer but rather a citizen who often reflects on things much more and is much more likely to bring their values into the discussion. It’s no longer just about the price. She said this is why we often see the disconnect where people say one thing in an interview but then make purchase decisions based on price.

“Imagine a young mother with two young children. She has three seconds to make a decision on what product she should buy,” von Keyserlingk said. “The kids are grumpy."

"The last thing they want is to be in the grocery store. In the three seconds she has, she is able to see one thing clearly, that milk prices vary; cartons that are the same size vary from as little as $2.50 to one that is $4 – and another is $8. She doesn’t have time to read about it all, right? But, in fact, she really does care about the cows and, in many cases, if she is reflective and her kids are at home, then, yeah, maybe she would be willing to pay more.”

Animal welfare defined

Animal welfare requires good health, positive experiences and natural living, von Keyserlingk said.

She clarified, “And by that (natural living), I mean what aspect of the environment do I need to tweak so that cow can express those behaviors that she’s highly motivated to express? That doesn’t necessarily mean that we’re going to send all cows on pasture all of the time. It is ‘Can she walk naturally?’ If we put down some really good friction flooring, does she have a more natural gait?”

Bottom line: Animal welfare needs to be discussed in the context of sustainability. For the solution to work, it must be environmentally friendly, economically viable and socially acceptable. It must be sustainable. There needs to be a balance among them. Just because we can do something does not mean we have the social licence to do so.

Animal welfare answers the question, “Should we do this?” not “Can we do this?” The goal is to find answers to guide best practices and do what is ethical, which is why a major component of von Keyserlingk’s research focuses on people and what is important to them. Her goal is to look 10 or more years out and do research that will help guide policy so farmers have reliable information to go on as the industry changes.

Two of her current areas of research are access to pasture and cow-calf separation.

Access to pasture: Should cows have it?

To answer this question, von Keyserlingk created a forum where farmers, veterinarians and the public could discuss hot topics in a safe environment. Participants could state their own views and vote on others. Of those surveyed, 90 percent of them said “yes,” and 10 percent were “neutral.” Even farmers overwhelmingly supported access to pasture; however, some stated that they’d like to give their cows access but can’t.

Others were concerned because they said pasture alone can’t fulfill the nutrient requirements of a lactating cow and keep her at the same level of production.

People often think that cows prefer to be on pasture. However, according to a preference test von Keyserlingk and her team did in 2009, cows prefer to be wherever it’s cooler. When given a choice, the cows stayed outside at night, but during the day, they stayed in the barn because it was cooler.

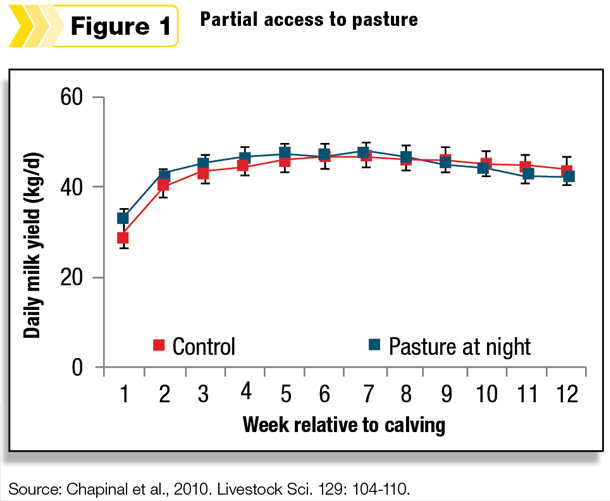

What’s more, in another experiment, her group allowed half of the cows access at night, and the other half were kept indoors 24 hours a day. Interestingly, the cows with access to pasture and the cows without access to pasture had the same level of TMR intake, and there were no differences in milk production for the first three weeks of lactation.

The next question: What qualities about pasture are important to cows? Is there something we could mimic in a barn to create a more natural living environment for them? Von Keyserlingk and the rest of the UBC Animal Welfare Program team members are currently researching the answer to this.

Cow-calf separation: Should we do it?

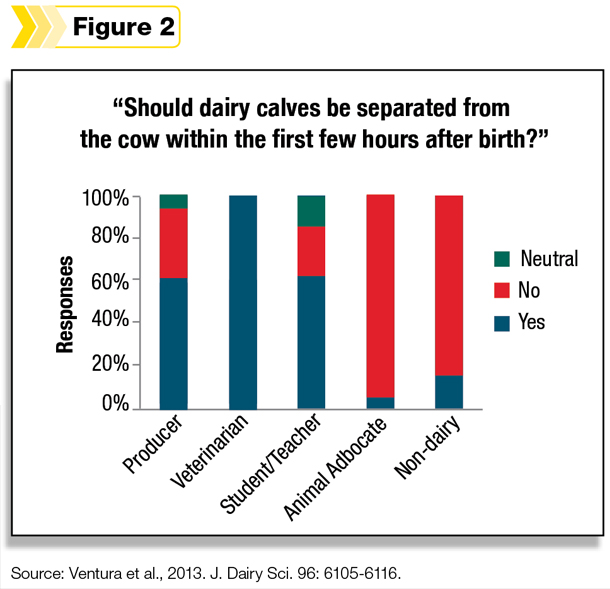

Again von Keyserlingk and her group surveyed people from a variety of backgrounds. Veterinarians were 100 percent against keeping cows and calves together since leaving them together posed a number of disease risks. Farmers all said they separated cows and calves; however, many said they don’t like to do it.

For this question, the public self-reported if they considered themselves an animal rights advocate or just non-dairy. The entire animal rights group voted against cow-calf separation, but even the non-dairy group clearly stated that they do not like the practice.

Although people voted yes or no on the issue, most of them used disease to justify their response but they argued in the opposite direction in many cases. For instance, some would say, “Yes, because separating the calf from the dam limits the window of exposure."

"It also decreases bonding and therefore there is less stress at separation.” Others said, “No, because separating the calf from the dam causes stress, making them more vulnerable to disease.”

Transition cow disease and calf mortality are major problems on many dairies. A critic could look at that and say, “It’s that high because you take the calf away from its mother.” The problem is, she says, there is absolutely no research proving that cow-calf separation has any impact on either of these issues.

“What can we say? ‘Well, that’s what we do,’” von Keyserlingk said. “I’m not saying that we should keep cows and calves together as of tomorrow. I’m just highlighting areas where we could potentially be vulnerable.”

Bottom line: There are a lot of questions without answers, and we need answers to those questions. We need to understand separation from more than a milk production standpoint, von Keyserlingk said.

The ideal dairy farm: What does it look like?

According to a survey one of her graduate students did of 453 Americans where they asked participants to answer a single question – What are the ideal characteristics of a dairy farm and your reasons why? – 60 percent said they were concerned about the cow’s welfare.

To them, an ideal dairy farm is one where there is no mistreatment of livestock, animals have access to pasture, and they are not treated with synthetic hormones or antibiotics unless it is absolutely necessary.

In another study where the UBC researchers looked to see if they could increase support for current dairy practices by increasing knowledge of citizens not familiar with the dairy industry, a number of interesting issues came forward. However, despite increasing knowledge, the big issue was that there are a number of common practices in the dairy industry that the public does not know about.

The participants in the study were pleased to see the high level of care on dairies but were displeased with the lack of access to pasture and cow-calf separation, von Keyserlingk said. They see cows with access to pasture and with their calf as a more natural environment.

While these changes are still down the road, they are coming. Animal activist organizations have them on their radar, she said. We need to be prepared.

We need to do research now so that we can discuss these issues with the necessary information and use science to help guide policy. Ultimately, we need to identify practices that are sustainable, which means that they should resonate with societal values. PD