To ready this article in French, click here.

The National Research Council (NRC) lists requirements for vitamins A, D and E in their seventh revision of “Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle,” published in 2001.

Supplemental D is listed as 21,000 IU per day for Holsteins, 13,500 IU for Jerseys, with most of the supplementation coming from the D3 (cholecalciferol) source.

Benefits of vitamin D in transition cows

Vitamin D is responsible for calcium and phosphorus homeostasis in transition cows, with positive roles in mineral absorption and bone deposition, and conserving both calcium and phosphorus at the kidney. The stakes are high – 98% of the body’s calcium is stored in the skeleton, and cows need to mobilize this from the bone in a timely fashion to support the production of colostrum and milk, to supply calcium for nerve and muscle function, and to avoid milk fever. Adequate vitamin D supports calcium absorption from the ration, storage in the skeleton and retention over time.

Is there a calcium gap?

There can be. High-producing dairy cows make major metabolic adjustments in the transition phase in order to support a profitable lactation. Thanks to modern management practices such as dietary cation-anion difference (DCAD) monitoring and strategic mineral management of forages and other ration ingredients, occurrence of clinical milk fever is rare, especially in younger cows. However, the incidence of subclinical (and clinical) milk fever increases with age and number of lactations.

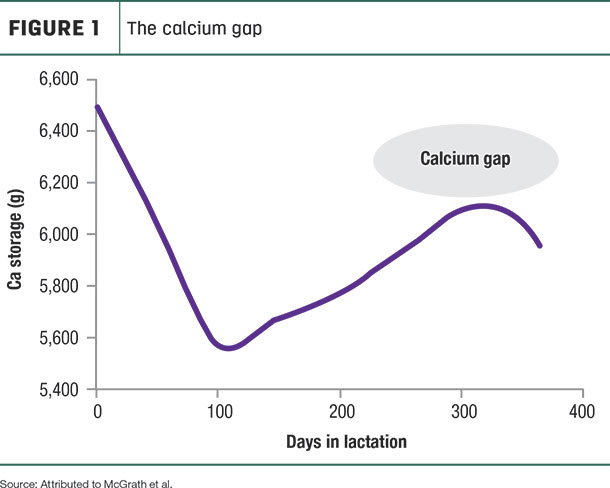

A majority of older high-producing cows mobilize enough calcium from their skeleton in early lactation that they experience subclinical hypocalcemia and then can’t catch up with their skeletal calcium storage for the rest of the lactation.

Figure 1 demonstrates an irreversible loss of about half-a-pound of calcium from a skeleton which initially contains 14 pounds in a 1,320-pound cow.

This “lactational osteoporosis” referred to in the Dairy NRC (2001) may not be harmful in one lactation but, over time, can deplete the skeleton of calcium and phosphorus, resulting in more incidences of subclinical hypocalcemia.

Sources of vitamin D

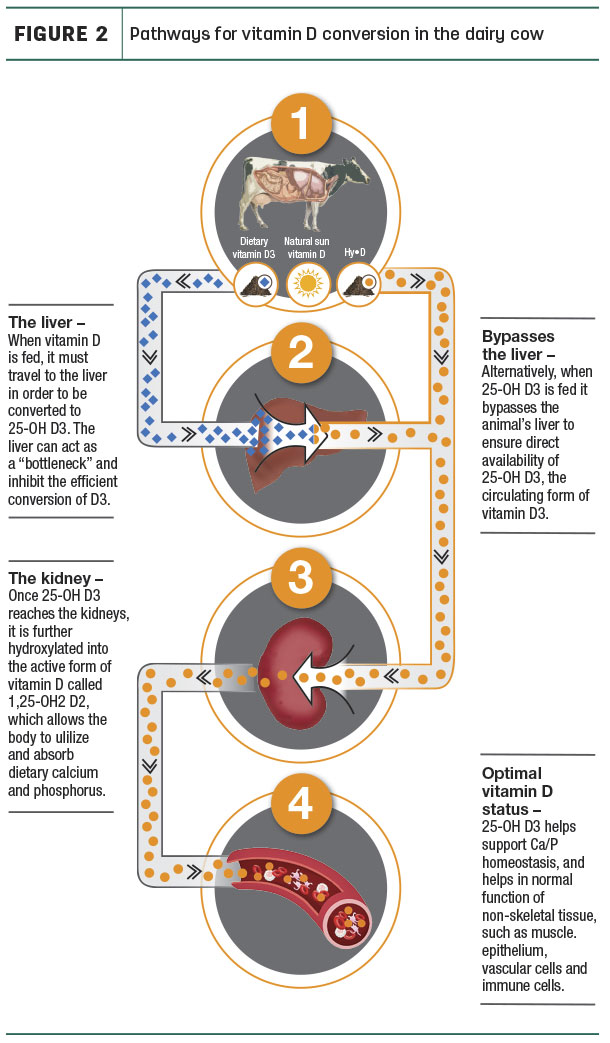

Unsupplemented cows obtain most of their vitamin D either from plant-based ergocalciferol (D2) or from sunlight exposure on skin, which converts cholesterol to 7-dehydrocholesterol, a D3 precursor. Main supplemental sources include D3 and, recently as a new source, 25-OH-D3.

As a prohormone, D3 must first be activated through a hydroxylation step in the liver to 25-OH-D3 and then by a second step in the kidney to the active, hormone form: 1, 25-OH-D3. In the bloodstream, 25-OH-D3 is the main circulating metabolite of vitamin D and now can also be fed directly – see Figure 2.

In addition to the kidney, many tissues can utilize 25-OH-D3 to synthesize the active 1,25-OH-D3 form, including gut epithelium, vascular cells, muscle and immune cells.

Action plan

- Check with your nutritionist to ensure adequate vitamin D is in the dry and lactating cow rations.

- Various close-up strategies, including DCAD or other calcium-mobilizing techniques, should be monitored closely to avoid hypocalcemia.

- To avoid a calcium gap, discuss your long-term calcium and vitamin D supplementation strategies with your nutritionist, especially for older cows.