In conversations with colleagues working in extension as well as with livestock and land managers around the country, we observed that particular assumptions and buzz words arise frequently and can dominate discussions in the realm of grazing management. Often-observed terminology includes regenerative grazing, holistic planned grazing management, multi-paddock grazing, management intensity grazing, high-intensity low-frequency grazing and Voisin’s rational grazing. An often-observed assumption is that rotational stocking is inherently superior to continuous stocking, regardless of the nature of the overall grazing system, and the presumption that continuous stocking implies overgrazing.

Lack of a clear definition and preconceived assumptions for these words/themes may promote misconceptions, thus hindering the opportunity for critical thinking and ultimately the advancement and improvement of grazing systems. In this article, we revisit assertions about grazing management in general, particularly the choice of the stocking method (rotational versus continuous stocking).

Terms like regenerative grazing and holistic planned grazing, while having gained acceptance in the popular press, are defined in very general terms. Their definitions contain undeniably important concepts (including social, economic and environmental), but they do not provide actionable items at the farm level. In this sense, they are more similar to the general concept of a grazing system. As a result of their very general definition, the elements of a grazing system that must be present for these approaches to be adequately implemented and tested are not well defined, and disagreements exist among advocates. Thus, critical and objective comparisons of these “systems approaches” with control systems are expensive, fraught with difficulty and essentially nonexistent in the scientific literature.

Terms like adaptative multi-paddock grazing (AMP), management intensity grazing (MiG), high-intensity low-frequency grazing, Voisin's rational grazing (VRG), are variations of the rotational stocking method; however, they are defined in general terms. For example, in AMP, "dense" cattle herds move quickly over the land followed by "adequate" rest periods for the regrowth of plants. MiG is "any" grazing method that utilizes repeating periods of grazing and rest among two or more paddocks or pastures, placing emphasis on the management. VRG is focused on adjusting the length of the rest period based on when the plants are "ready" to be grazed. Some may wrongly assume that the land manager implementing rotational stocking is using a rigid system and may have no ability or desire to adjust rest periods, grazing times or stocking density based on current observations of the landscape. However, the capacity to adapt to a changing environment has been and must continue to be a daily practice for the land and livestock manager, and this practice is not limited to a specific grazing system or stocking method.

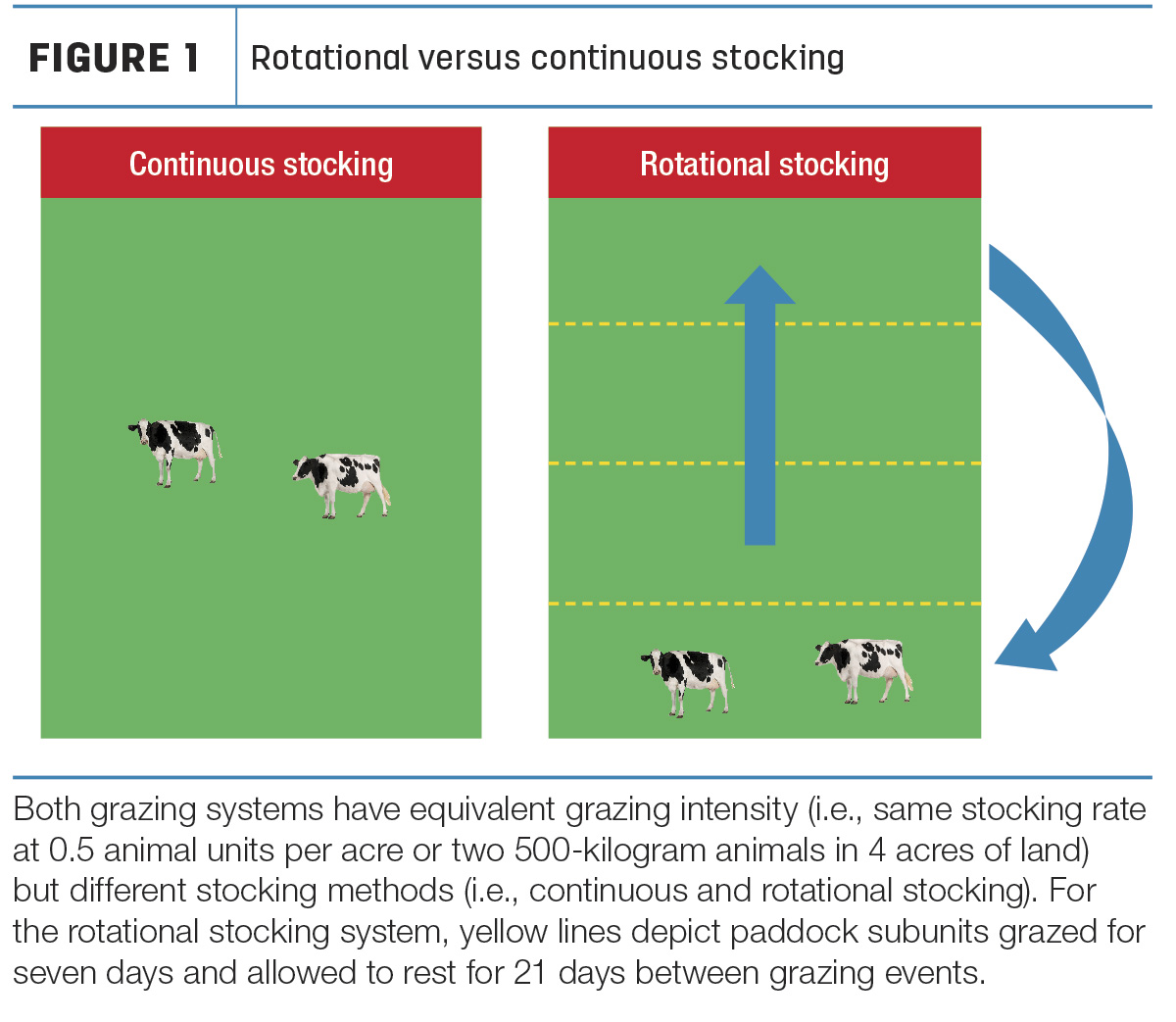

Grazing management is characterized in terms of intensity, method, timing of grazing, and type and class of livestock. The choice to use a particular level of any of these management strategies should be objective driven. It is important to recognize that choice of stocking method (i.e., rotational versus continuous) is only one element of grazing management, and grazing management is only one element of a grazing system. Thus, stocking method is one piece of a very large pie. It is unfortunate that choice of stocking method dominates discussions of improving grazing management to the expense of other issues, when in fact, intensity of grazing has been shown conclusively to be the most important determinant of a wide array of soil, plant, animal and ecosystem responses.

We noted that the so-portrayed “adaptative, novel or non-traditional” grazing management approaches tend to favor rotational over continuous stocking as the stocking method of choice. In fact, some have labeled rotational stocking as an improved management and continuous stocking as the conventional management (or business as usual), creating a false dichotomy, that is, a good/bad scenario. In some cases, continuous stocking is also incorrectly presumed always to be associated with overgrazing. As a result, improved management and tacitly rotational stocking is directly linked with environmental, economic and social benefits. Thus, choice of stocking method tends to dominate discussions about how to improve grazing systems, completely obviating a more important grazing management practice, intensity of grazing.

If rotational stocking, as portrayed by so-called “non-traditional” words/themes as previously described, is so critical, then several questions arise. For example, what specific outcomes are improved in rotational versus continuous stocking, and to what extent? What are the mechanisms that explain those responses? We framed these assertions in the form of questions.

Does choice of rotational stocking ensure well-managed pastures?

Rotational stocking is no guarantee of proper grazing management; overgrazing and its deleterious effects can occur under rotational stocking if the stocking rate is excessive. Likewise, continuous stocking is not synonymous with mismanagement. The most important aspects of grazing management are ensuring an adequate quantity of forage and soil cover (as a proxy for intensity of grazing) and forage nutritive value. There may well be grazing systems with particular forage species, categories of animals or economic attributes that cause continuous stocking to be the preferred stocking method. Likewise, rotational stocking may be the obvious best choice in other situations.

Does rotational stocking result in a greater accumulation of soil carbon than continuous stocking?

There is limited evidence that stocking livestock rotationally promotes better soil condition or soil carbon accumulation compared with continuous stocking. The above referenced chapter of the Natural Resources Conservation Service literature states “... essentially no data are available in the scientific literature from the humid region of the USA to support a claim for positive effects of rotational stocking alone, or in comparison with continuous stocking, on soil erosion or soil condition.” Implied in this statement is the overriding importance of grazing intensity of the wide array of grassland responses. Soil condition as referred to by the authors in 2012 most likely equates to soil health these days.

We argue that plant growth, including and perhaps especially below-ground biomass, and soil cover are key promoters of soil health. Animals are tools to impose defoliation, hence induce tissue turnover, forage regrowth and recycling of nutrients. Proper grazing management, in that sense, can be achieved independent of the choice of stocking method, if the requirements of the grazing system as a whole are considered.

Does rotational stocking increase pasture productivity and stocking rate compared with continuous stocking?

Across many published studies, planted pasture productivity or average optimal stocking rate increased an average of 30% for rotational compared with continuous stocking. Greater forage productivity or ability to support a greater optimal stocking rate are attributed to greater efficiency of grazing (i.e., more uniform forage utilization in space and time) and greater overall canopy photosynthesis because of a more-favorable average leaf-age profile under rotational than continuous stocking.

There is evidence to support that uniformity of nutrient return can be improved with rotational stocking, and this can positively impact pasture production. However, to say if you start rotating animals you do not need to add nutrients to the system is a problematic and unsupported statement, as natural losses (e.g., leaching, runoff and volatilization) and product removal (e.g., hay, weight gain, milk produced) result in nutrients exiting the system. In fact, grazing animals do not “add nutrients,” but recycle them. Nutrients can be added via fertilization (e.g., from mineral or organic sources), supplementation (through the animals) and biological nitrogen fixation (specifically for nitrogen). Lightning is another source adding small amounts of nitrogen.

Our intent with this brief reflection is to clarify terminology and concepts that frequently get lost in the weeds and not to antagonize any current trends in pasture management. We believe most of us will agree in many of the key principles; however, some misconceptions can be carried on and we lose sight of the actual mechanisms behind the phenomena we are observing. We hope this brief reflection on stocking method and terminology can add to the discussion of livestock production systems and bring more clarity to conversations about this topic.