What does it matter whether we call it a cover crop or winter forage? In the grand scheme of things, it probably doesn’t, aside from the endpoint of what you will do with the crop. A quick online search yielded the following generalized definitions:

Cover crop: In agriculture, cover crops are planted to cover the soil to enhance crop diversity, improve soil quality and fertility, and minimize soil erosion, rather than for the purpose of being harvested.

Winter forage: Crops specifically planted to harvest in the spring, probably ensile, that also serve all practical purposes of a cover crop over winter.

Small-grain winter forage provides a valuable opportunity for many operations. Wheat, barley, oats, rye and triticale can be harvested and ensiled to provide large quantities of high-quality forage throughout the year. Most producers using this type of program experience increased annual forage yield per acre while gaining cover crop benefits (e.g., minimizing soil erosion). Currently, triticale is gaining favor as the preferred winter forage in many areas of the country. As winter forages gain in popularity, we need to remember: They are not corn and are not alfalfa. Best management practices need to be modified to work with the biology of these plants.

Interestingly, when "cover crops" serve as "‘winter forages" in a finely tuned agronomic program, there are numerous benefits. Recent interest in triticale as a winter forage is also driving increased interest in planting sorghum. Research by Tom Kilcer at Advanced Ag Systems LLC has found that triticale winter forage directly increases annual yield per acre by 35% while improving soil health and structure.

Tom states, “The forage quality is outstanding and is key to eliminating the ‘summer slump’ when included in the ration as the summer heat builds. In the spring, winter forage is ready to harvest first, then haylage harvest can follow immediately after. Any corn planting would have to be delayed until after haylage and could potentially suffer yield loss. Summer sorghum and winter triticale forage rotation is a natural fit.”

We have focused our attention on management of the silage-making process with particular emphasis on potential bottlenecks to making high-quality silage. We refer to these factors as critical control points (CCPs). Each of the eight CCPs are described next with particular attention paid to management factors that can enhance small-grain winter forage silage quality.

CCP 1: Safety – Safety matters. Have we done everything possible to ensure safety for us, our employees and our family members?

CCP 2: Decision-making – Who is empowered to make the decision to start, alter or stop the harvest and ensiling process? This should be done prior to harvest and needs to be clearly communicated with all team members.

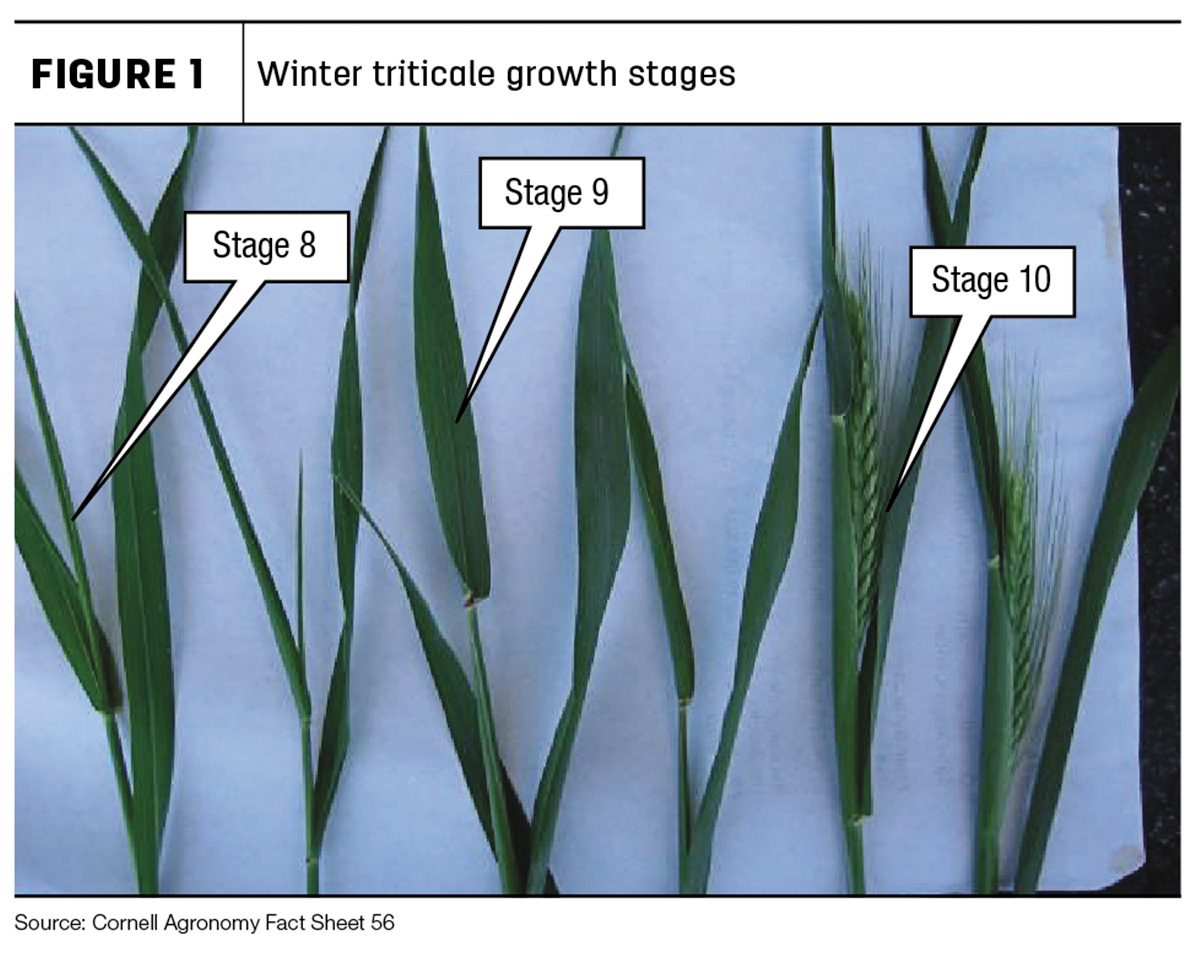

CCP 3: Maturity – This is key to the antagonism between quantity (yield) and quality (digestibility). Ultimately, the decision of what maturity to harvest depends on the species of small grain, the crops or forages that will be planted afterwards, other planting activities on the farm and the class of animals that will be fed the small-grain silage. Often, small-grain silage yield and quality are optimized at the late-milk stage to soft-dough stage. There will be about a five- to 10-day window to harvest winter triticale once it reaches the flag leaf growth stage (Feeks Stage 9; Figure 1).

The seedhead will still be in the stem, somewhere between half and three-quarters of the way up the stem. Once the seedheads are visible at the top of the stem, the triticale has reached boot stage (Feeks Stage 10), and forage quality will start to decline rapidly. Winter triticale will still make a decent feed for heifers and dry cows and will continue to increase in tonnage up to the late boot stage; however, as it matures, the hollow stem will trap air and oxygen in the forage mass during ensiling, leading to fermentation challenges.

CCP 4: Moisture – The target moisture for small grains to ensile should be about 66% (34% dry matter). Consider the crop, storage structure and the class of animal being fed the silage when determining your target moisture. Similar to other crops, when winter forages are harvested with a lower-than-ideal dry matter (DM) content, they are at an increased risk of clostridic fermentation, a slower pH decline and an increase in effluents.

CCP 5: TLOC – Theoretical length of cut (TLOC) should be 1/4- to 1/2-inch. This facilitates optimal packing, leading to a more robust fermentation, and works nicely in most total mixed rations (TMRs).

CCP 6: Silage inoculant – An effective inoculant can mitigate some of the oxygen issues during ensiling and at feedout, and drive fermentation toward a desirable endpoint. Remember, if maturity advances beyond soft dough, small grains begin rapid lignification of stems that are hollow. These hollow stems, when chopped for silage, trap air and oxygen. Oxygen is the enemy of fermentation of forages. Furthermore, oxygen promotes the growth of yeast and molds that need oxygen to survive.

One such science-based, research-proven inoculant combines an outstanding oxygen scavenger (Lactococcus lactis O224) with a heterofermenter (Lactobacillus buchneri 1819). The L. buchneri produces acetic acid which improves aerobic stability through its anti-fungal properties. Minimizing fungal growth leads to cool, stable forage during feedout. An additional benefit of this bacteria combination is early opening.

CCP 7: Packing – A sound approach to packing is warranted for small-grain silages. Hollow stems and air entrapment in the forage are the reasons why diligent packing is necessary. Adherence to the "Rule of 800" (packing tractor weight required = 800 x tons of forage delivered per hour) is mandatory.

CCP 8: Sealing – Once packing is complete, smooth the top-layer surface to minimize the impact of tire ruts. This will allow the plastic to adhere more tightly to the top-layer surface of the forage and minimize air and oxygen presence. Oxygen barrier plastic and (or) the use of a top-layer spray-on can minimize top-layer spoilage. Cover quickly, efficiently, thoroughly and safely. Make sure the tires are touching.

Although the eight CCPs described previously are important for successful harvest and ensiling of small grains, the most important CCP for high-quality small-grain silages are maturity, moisture, inoculant and packing. It doesn’t really matter what you call them – cover crops or winter forages – as long as the attention to detail for the CCPs is tailored to the crop.