Since I graduated from veterinary school almost 30 years ago, there have been big shifts in the types of mastitis found on farms.

We used to mostly deal with contagious mastitis cases, which we’ve done a good job of managing. Now the mastitis we’re seeing more often are environmental cases, including gram-negatives like Escherichia coli.

E. coli is different from the mastitis cases we used to see because it’s not simply a somatic cell count (SCC) issue. It’s a cow health issue. As environmental pressures such as herd size, stocking density and milk production increase, we’re going to continue to be challenged with gram-negative mastitis.

E. coli is known for its quick onset and clinical signs that range from mild to fatally severe. The cow’s immune system is actually adept at dealing with E. coli, but as the cow eliminates the bacteria, endotoxins are released. This is why some cases of gram-negative mastitis become severe enough to be fatal. Animals that do recover from a severe case never really make it back to the peak production they once were at. Thankfully, gram-negative mastitis is a problem we, as producers and veterinarians, can prevent and manage by focusing on a few key areas.

1. Address the cow’s environment

E. coli and other types of gram-negative mastitis strains are found virtually anywhere cows are housed, such as in bedding, the milking parlor and manure. We have to keep their environment as clean, dry and comfortable as we can to prevent teat ends from getting exposed to manure. This includes frequent scraping of alleys and holding pens, as well as keeping stalls, or wherever cows lie down, well-bedded and maintained. We also want to try to keep the barns properly ventilated. If the barn is wet and humid, there’s going to be more heat stress and a bigger risk of spreading bacteria.

The second part of managing a cow’s environment is following good milking procedures. That means making sure milking equipment functions properly and teats are clean and dry before attaching milking equipment. To maintain hygiene in the milking parlor, remember the following:

- Wear gloves – Bacteria are less likely to adhere to gloves; wearing them can reduce the risk of spreading mastitis-causing pathogens from cow to cow.

- Pre-dip – Pre-dipping with an effective sanitizing solution kills any lingering bacteria on the teat end.

- Dry thoroughly – Ensure the teats and udder are completely dry. Remaining water may contain bacteria and contaminate the teat end.

- Detach the milking unit carefully – To prevent teat-end damage and decrease risk of infection, ensure the vacuum is shut off before removing the milking unit.

- Post-dip – Post-dipping with a germicide protects the vulnerable teat end from coming in contact with mastitis-causing pathogens.

- Monitor the parlor water – Water used in the parlor can hold hundreds of coliforms per cubic centimeter. Consider medicating the water with iodine or chlorine to ensure the water used to clean milking units does not introduce bacteria that may cause mastitis infections.

2. Enhance the cow’s immunity

If faced with E. coli, cows need to have a robust immune response to fight off the infection. Building immunity involves a strong nutrition program that includes trace minerals and plenty of water, as well as routine vaccinations.

Vaccination is critical in reducing the severity and incidence of E. coli. Most E. coli infections are going to happen right around freshening, due to increased stress, so I recommend getting ahead of the problem by vaccinating all cows at dry-off, then giving a booster vaccine four weeks later. The vaccine you choose should have a short meat withdrawal and provide protection against E. coli, endotoxemia caused by E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium.

3. Treat thoughtfully

If you think you’ve got an animal experiencing a case of E. coli, before you reach for any sort of treatment I suggest taking two steps:

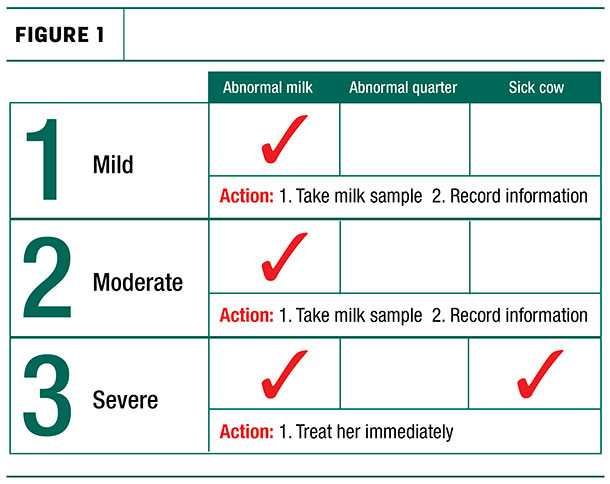

- Grade the mastitis to determine the level of severity (Figure 1).

- Take a milk sample, culture it and wait for results.

Most mild to moderate gram-negative mastitis cases, including those caused by E. coli, will self-cure and do not require antibiotic treatment. However, in severe cases where the cow is visibly sick, start treating immediately with fluids, anti-inflammatories and injectable antibiotics, then adjust treatment as needed based on the culture result.

If you’re dealing with a gram-positive pathogen, find a short-duration treatment (one to three days) to get cows back in the tank as soon as possible. Ideally, the tube has a tip that allows for partial insertion, since long tips can drag bacteria up into the teat.

No matter your mastitis treatment protocol, following the product label is imperative to ensure a safe food supply. Product labels contain important information including indications, dose, route of administration, treatment duration, milk withhold and meat withdrawal times, class of animals (lactating or non-lactating), as well as treatment frequency and duration.

Lastly, and most importantly, your herd veterinarian is your best resource for preventing and managing E. coli. He or she can help develop a control program tailored to your operation’s specific needs.

References omitted but are available upon request by sending an email to the editor.