Two things commonly known about fats are: 1) we can add them to dairy rations to improve the energy in the diet, and 2) too much fat from grains, oilseeds and byproducts, such as dried distillers grains (DDGs), can reduce milkfat production. Forages, grains and protein ingredients all contain some fat. But these fats are not alike. Through research, we are constantly gaining new knowledge on how to better utilize the different fats to improve dairy feed performance.

Fats are composed of fatty acids, and the makeup of these fatty acids has a huge impact on how the fats perform. The first term to understand is “saturated.” Fatty acids that are saturated are unreactive and can be added to the diet without worry that milkfat will be impacted. These fatty acids have a high melting point and are therefore solid. In contrast, unsaturated fatty acids are reactive and can be a cause for worry if not properly monitored when added to diets. These fatty acids have a lower melting point and are generally liquid at room temperature.

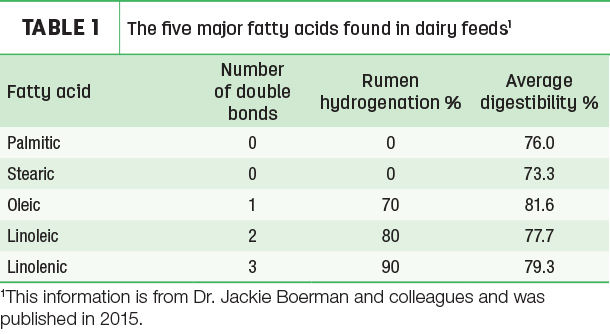

While there are many fatty acids, the five major ones are listed in Table 1.

The fatty acids all have a carbon framework, with sites along the framework that can be occupied with hydrogen. When all the sites are occupied, the fatty acid is saturated. When the sites along the carbon framework are not fully occupied, the fatty acids are unsaturated. So, looking at Table 1, palmitic acid (which takes its name from palm fat) and stearic acid (which gets its name from tallow) are saturated.

Oleic acid has only one double bond and is a monounsaturated fatty acid, while linoleic and linolenic acids are polyunsaturated because they have more than one double bond. The double bonds are simply sites that are not full of hydrogen.

Hydrogenation is the process of adding hydrogen to the parts of the fatty acid framework where they are missing. When oleic, linoleic and linolenic fatty acids are fully hydrogenated, they are converted to stearic acid and become inert in the rumen. The rumen microbes hydrogenate fatty acids to varying degrees. As Table 1 shows, on average, 70%, 80% and 90% of oleic, linoleic and linolenic fatty acids are hydrogenated to form stearic acid, and the rest escapes the rumen for the cow to digest.

Importantly, the hydrogenation process has several steps, and some of the intermediate steps can produce partially hydrogenated intermediates that, when digested, can interfere with milkfat synthesis. These intermediates are most apt to occur with the polyunsaturated fatty acids and much less so with oleic acid. Furthermore, according to Dr. Louis Armentano from the University of Wisconsin, linoleic acid is the one most likely to cause the milkfat-reducing intermediates.

When the fatty acids enter the intestine, they are digested by the cow. As Table 1 shows, there are differences in digestibility, with oleic acid being the most digestible.

In summary so far, oleic acid seems rather special. Oleic acid has the highest potential to escape the rumen, the highest intestinal digestibility and the least likely unsaturated fatty acid to reduce milkfat. There are other unique attributes of oleic acid as well.

Additional research conducted by Dr. Jackie Boerman at Purdue University indicated that the digestibility of fatty acids declines as the fatty acid level of the diet increases. The effect is, however, much less pronounced with palmitic and oleic acids than the remaining three fatty acids. And even more interesting, research conducted by Dr. Crystal Prom at Michigan State University showed that oleic acid could improve the digestibility of saturated fatty acids. When more oleic acid was available, it could improve the overall digestibility of fats.

Another well-recognized benefit of unsaturated fatty acids is their ability to reduce the greenhouse gas methane. Canadian researcher Dr. Karen Beauchemin, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, showed that the monounsaturated fatty acid, oleic acid, is more effective in doing this than the polyunsaturated fatty acids.

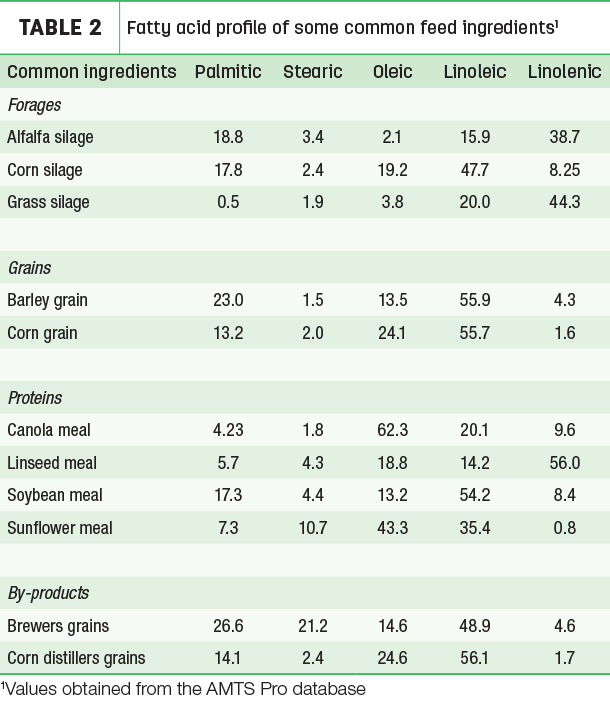

The research points to numerous advantages for oleic acid, so it is curious to know some of the sources of this, as well as the other fatty acids that impact production. Table 2 provides the key fatty acid profiles for some common ingredients.

It is easy to see that soybean meal, barley and corn products all have the highest levels of linoleic acid, the fatty acid most likely to negatively affect milkfat percentage. Grass and legume forages, along with linseed meal, are sources of linolenic acid and can be helpful in diluting the linoleic acid from the other sources in the diet.

Fatty acids from canola meal and sunflower meal provide the greatest amounts of oleic acid. These can be helpful in protecting milkfat percentage, improving digestibility and reducing the greenhouse gas methane.

The findings with oleic acid demonstrate the importance of research to improving how we feed cows. We are learning that fat is not just fat, and that we can manipulate the ingredients used in diets to ensure we have consistent results and optimum digestibility.