Feedyard managers, beef processors and truckers all agree that finished cattle have outgrown the equipment used to haul them. And bruising has created both a product quality issue and a significant animal welfare concern.

Kansas State University (KSU) researcher Daniel Thomson has reported some of the causes of carcass bruising in finished cattle at several industry meetings. He reports that producers are feeding cattle that are larger and taller than they were even five or 10 years ago, but the trailers used to haul them are the same size.

“Bruising is caused by cattle hitting their backs during the transport process, including loading and unloading,” Thomson explains. “We suspect that different trailer types contribute to the bruising we see on the carcasses of finished cattle.”

Today’s larger cattle are squeezing through a belly gate that has a 56-inch clearance. The belly or bottom compartment has 69 inches of clearance. Thomson discovered that rib and hip areas often have bruising, but a whopping 53.3 percent of bruising occurs along the topline (midline), which includes the valuable loin area.

Because bacteria are more likely to grow in bruised tissue, it is unsafe for human consumption. Bruising is costly to the beef industry because damaged tissue must be discarded.

Removed tissue is usually rendered into meat-and-bone meal, which is often fed to poultry, and tallow, an energy source for animal feeds, according to Ty Lawrence, director of the West Texas A&M University Beef Carcass Center.

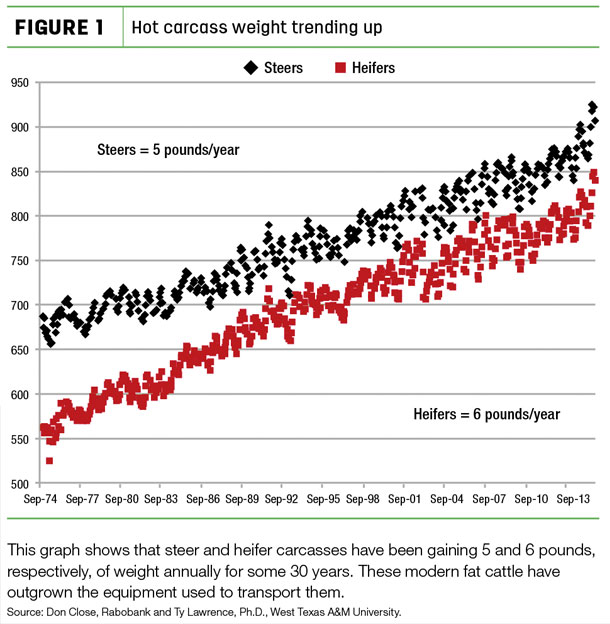

Lawrence reports that studies indicate steer and heifer carcasses have been adding 5 and 6 pounds, respectively, of weight each year for some 30 years. Economics is the main incentive to push animals to gain more weight, because cow-calf producers, stocker operators and cattle feeders are all paid primarily based on pounds.

Beef processors continually increase the heavy carcass weight limit to spread fixed and variable costs of running the facility over more pounds. This practice has resulted in larger animals that have outgrown both facilities and trailers.

“Many of the trucks and trailers are the same size they’ve always been – 53 feet long and 8.5 feet wide,” Lawrence explains. “Bruising is painful to the animal to some degree. In an ideal animal-husbandry world, you’re handling them in a low-stress environment, taking your time [as you work the animals].”

Minor changes

Proper handling reduces stress and improves productivity, quality and value. The good news is that producers at every level of the beef cattle industry can make minor changes to reduce bruising. For example, 30-year-old feedlots that have kept the same snakes (single-file alleys) and chutes can update their facilities by widening them.

Although it may not be possible to avoid all trauma, transporters can do their part to minimize bruising. Practice low-stress handling techniques when loading and unloading stock. Take an online class to learn low-stress handling techniques from Beef Quality Assurance at PQA Programs.

Many producers haul stock in gooseneck trailers that have slick floors. Consider placing slip-resistant rubber or synthetic flooring, which is available from equipment dealers, in smaller trailers.

“Think about the cattle,” Lawrence advises. “Treat them as if you owned them, rather than [thinking about] the miles you’re going to drive today. Slow down. Take your time with the cattle. These living animals are going to be food in a relatively short time, especially if you’re hauling them to harvest. Treat them as such. They are someone’s livelihood.”

Trevor Caviness, president of Caviness Beef Packers in Hereford, Texas, is the third generation of his family to work in the beef-packing business. He says his company makes it a point to adhere to the guidelines of the “Recommended Animal Handling Guidelines and Audit Guide: A Systematic Approach to Animal Welfare” when transporting cattle.

“This program was written by Temple Grandin, professor of animal science at Colorado State University, and is certified and accredited by the Professional Animal Auditor Certification Organization (PAACO),” Caviness explains. “Caviness [Beef Packers] has three full-time employees that are PAACO certified and ensure daily that our animal-handling employees meet the highest standards of animal welfare.”

Caviness advises producers to pay attention to livestock pen design and try to improve on any potential hazard that would cause bruising during cattle flow.

Caviness advises producers to pay attention to livestock pen design and try to improve on any potential hazard that would cause bruising during cattle flow.

“Herringbone pen design helps eliminate hard angle 90-degree turns,” Caviness advises. “Cut down or eliminate electric prod use and handle cattle in a very calm manner. Gone are the days of hooting and hollering. Bruises on beef carcasses are a real loss to the producer. We see bruising in many carcasses each day.

All bruises must be removed for the carcass to pass USDA FSIS (Food Safety and Inspection Service) inspection. Small bruises may be 2 to 3 pounds per head of trim loss and large bruises could amount up to 100 pounds per head. Most bruises are seen on the midline of the carcass and at the hook, pin and tail bones.”

Addressing the issue

The folks at Wilson Trailer have known for some time that cattle are increasing in size. Tim Mahal, director of engineering at Wilson Trailers, is working on solutions to prevent bruising in fat cattle.

He reports that experts in the engineering department at Wilson Trailers are working with trucking companies that haul large cattle, aggressively redesigning various items in the trailer that have been known to cause bruising.

“We’ve tried to address this issue of larger cattle,” Mahal says. “In the past, we had a flip-up ramp in that upper deck for really big cattle, such as 2,200-pound Brahmas, but we found Herefords and Holsteins are getting taller. We have customers that haul those on a regular basis. They’ve asked us to increase space for cattle.”

Because all trailers haul weight based on axle-weight capacity, many operators have converted to tri-axles to allow for a heavier animal load. Wilson has also designed stronger floors supported by new crossbars to accommodate more weight.

The company has shortened the upper deck some 9 inches to increase the back clearance by several inches. Mahal reports that in some models they have moved ramps from the rear deck to the side, which gives taller Holsteins more room to maneuver.

Traditional rectangular gates have been changed to those that are wider and rounded to avoid bruising. Mahal and his colleagues constantly look for ways to improve trailer designs. Several trucking company owners have ordered new trailers with customized modifications that minimize bruising.

Tiffany Lee, director of regulatory and scientific affairs for the North American Meat Institute, worked with Thomson for an advanced degree on this KSU study.

“It’s an animal welfare issue,” Lee reports. “Whenever any kind of injury or bruising happens, it reflects on animal welfare. Hopefully, continued research in this area will help to decrease the amount of bruising and increase animal welfare.”

Although research to determine all causes of bruising before, during and after transport is ongoing, this continues to be a serious problem in finished cattle. The upside is that there are workable, commonsense solutions that producers in every segment of the beef industry can apply to minimize bruising in America’s beef supply. ![]()

PHOTO: All bruises must be removed to pass the USDA FSIS inspection. This involves removing 2 to 3 pounds per head of trim for small bruises and as much as 100 pounds of trim for large bruises. Photo courtesy of Trevor Caviness, Caviness Beef Packers.

Gilda V. Bryant is a freelance writer from Amarillo, Texas.