Solitude is the necessary incubator of creativity and, for those who have chosen to live in sparsely populated areas of the Western states, where cows outnumber people by a factor of X, aloneness forces one to think beyond self.

Rather, what role does self play in becoming an integral partner with the landscape?

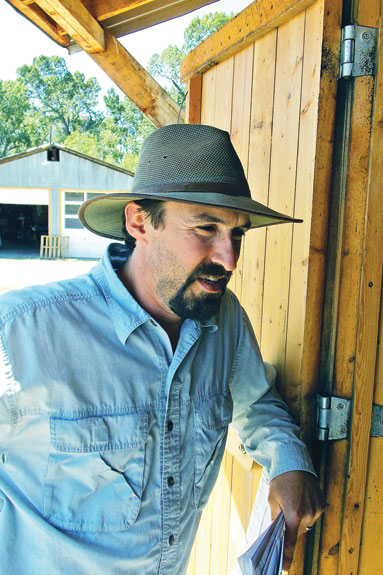

At 33, Zach Jones is a son, husband, father and philosopher. In the open spaces of central Montana, he plays the role of all four, plus ecologist as he labors each day to manage the grass that provides wealth for him and many others.

“I was never going to be, nor will I be, the guy with the clipboard,” he says on a bright summer morning that would be suffocatingly hot by mid-afternoon.

Jones earned a degree in physical education at Montana State University in Bozeman, where he was a member of the track team.

Principles vs. details

Although he grew up on the family ranch that dates back more than 100 years, “I was adverse to studying animal science,” he says.

As a youth he liked baseball and never did rodeo or belong to 4-H. “Maybe I was insecure about it,” he muses.

But when he returned to the ranch to join his father, Bill, “I had the confidence that I could figure it out.”

“At the time, I was oblivious to holistic management,” he says. It was a course at MSU entitled “Life and Other Big Questions” that began to form his philosophy about caring for the land.

“Why do we ranch and farm?” he asks. “I was thinking about what it means to be in this place.” It also required him to “de-learn or to learn what you need to forget.

You have to be open-minded on these landscapes. To be a generalist. To be a scholar and athlete in mind, body and spirit.”

Then it comes to principles versus the details, he says, and to implement a philosophy of land management. “The hands-on work I do gives me opportunities for influencing how things are done.”

That led him to holistic management, the Savory Institute and Grasslands LLC. Jones took up the practice of intense grazing as advocated by Allan Savory, of Zimbabwe, who in the early 1980s encouraged U.S. range managers to increase their stocking rates but to move their animals frequently, like the migrating herds on the African veldt.

Three years ago, Jones joined six others, including Savory, to form the Savory Institute, a for-profit entity, to engender a renewed commitment to improving the range soil by intensively managing forage resources.

The institute has acquired capital toward land purchases for investors. Grasslands is the management arm.

Jones is the chief operating officer. Grasslands oversees the stocking of 105,000 acres on three ranches in South Dakota and Montana. Jones also oversees his family’s 12,000 acres.

The hands-on requirements keep him on the road, traveling frequently to the three operations.

Although drought scorched agriculture lands across the West, it was not severe in Montana. However, stocking rates this year are below 2011, he says.

New hands, old ideals

To implement the grazing plans for his own ranch, Jones enlisted two young men as interns who received the on-the-ground training they want for their own futures.

Sebastian Worms, 20, calls Waterloo, Belgium, home.

His father, a public relations executive, was in Zimbabwe and met Savory and wrote a story about him and his ideas.

“I wanted to be part of it,” says Worms.

So he snared an internship with Grasslands, spending three weeks in South Dakota before coming to the Jones ranch.

A biology-chemistry major at the Catholic University of Louvain, one of the most prestigious in Europe, he anticipates a master’s degree by 2015.

But for this summer, he herded cows and moved electrical fence using a four-wheeler instead of a horse.

“It was a bit frightening at first,” he admits, “but these are really fun things to do. There is the responsibility for the cows, not just letting them roam.”

His girlfriend was “jealous” of his summer job, he says. They kept in contact by email.

The range management experience has presented new options on how he might use his knowledge after university.

He expressed an interest in future economic opportunities in China and India. He speaks English, French and German.

For Paul Wesley Quin, 23, there is only one goal: to own and operate a ranch.

Conventional wisdom nowadays says that to get a ranch you have to be born into it or marry into it.

“I am going to prove everyone wrong,” he says. “If you want it bad enough, you can get it.”

Quin, of Pilot Point, Texas, is a senior at Texas A&M.

Next spring he’ll receive his degree in rangeland ecology management with a minor in agronomy. His life’s work will be to “raise cows and keep the grass healthy.”

Simply put, his summer internship made him realize, “I love the land more than I thought. I learned how to move cows with low stress and stockmanship; how to design electric fencing to keep them where they are supposed to graze.”

He wants to be a good steward, to follow Aldo Leopold’s land ethic. He references the last chapter of Sand County Almanac as his guide. That and his namesake’s First Corinthians.

PHOTOS

PHOTO 1: The Jones Ranch on the Montana-South Dakota stretch applies intensive forage management under the Savory model.

PHOTO 2: Zach Jones, 33, of Harlowton, Montana, discovered a new connection to his ranching roots through a college class on holistic range management.

PHOTO 3: Sebastian Worms, 20, of Waterloo, Belgium, is a summer intern on the Jones Ranch. He is a student at the Catholic University of Louvain.

PHOTO 4: Paul Wesley Quin, 23, of Pilot Point, Texas, is an intern and senior at Texas A&M. Photos courtesy of Jim Gransbery.