Recent data gathered by Benchmark from feedyard owners over the past four years, and shared by Elanco Animal Health, show an increase of herd health spending going from $12 to $13 per head in 2010 up to $16 to $17 per head, according to Nathan Pyatt, a beef technical consultant for Elanco.

Unfortunately that investment per head still isn’t equating to lower death loss in the feedyard.

The Benchmark database is the largest finishing cattle database in the U.S., according to Pyatt, consisting of about 250 producers who submit data on a regular basis.

The producers providing data have about 45 to 55 percent of the cattle on feed, depending on the cattle cycle. Data collected by Benchmark are related solely to the finishing stages of cattle production.

Pyatt says producer responses for medical investment are based on veterinary medical charges. That includes charges for animal health products, vaccines, implants, antibiotics, as well as labor and facility charges.

“We’ve seen an annual increase of around 60 cents to one dollar per head, in both steers and heifers, across the last five years,” Pyatt explains. “That would be just in specifically the 700- to 799-pound heifers and steers that were placed in feedyards.”

But while the dollar-per-head spending has risen, it hasn’t been specifically designated to any particular area of cost. “Some feedyards may have higher metaphylaxis uses; some may have higher vaccination protocols and booster programs.

Some may use a more aggressive implant program, or some may have varying rates on labor and facility charges. We haven’t been able to dissect that out specifically.

“But what’s more alarming is that the increase in investment hasn’t led necessarily to decreases in animal mortality rates. That’s what’s probably the biggest concern we have. We’re investing more, but not necessarily getting any more in return, in terms of animal health protocol outcomes.”

Identifying death loss factors

Pyatt says the mortalities seem to be related to lighter weight cattle entering the feedyard, and those lighter cattle then requiring longer time in the feedlot.

“Inherently those animals that are lighter weight have a higher risk. Whatever their immune capacity is or the duration they stay in that finishing lot, they have longer exposure potentially and again are less competent than heavier cattle that come in with greater maturity in that regard.”

Those findings are supported by a 10-year-data study reported by a team led by Dr. Gary Vogel, detailing feedlot closeout records and mortality factors.

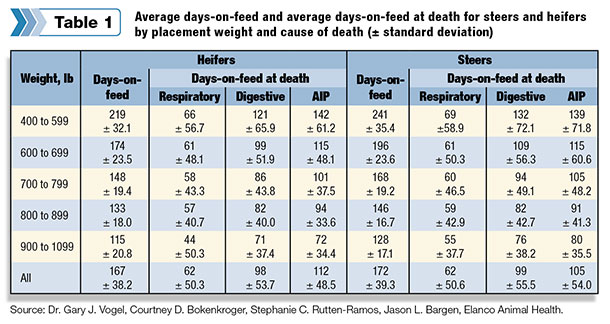

Analyzing data for 73 million head of cattle at 484,193 pens over four years, Vogel broke down the timing of death losses into four categories: the first 30 days livestock are on feed, the final 30 days and two middle portions (31 days on feed to 61 days prior to harvest, and 60 to 31 days prior to harvest).

Cattle deaths were classified by respiratory (BRD and pneumonia), digestive (bloat, acidosis, coccidiosis), acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) and then other injuries or weather-related factors.

The study found the combined steer and heifer mean yearly mortality rate was 1.49 percent. Yearly mortality increased 27.6 percent (1.34 percent to 1.71 percent) in steers and 30.5 percent (1.41 percent to 1.84 percent) in heifers between January 2005 and September 2014.

Mortality linked to duration

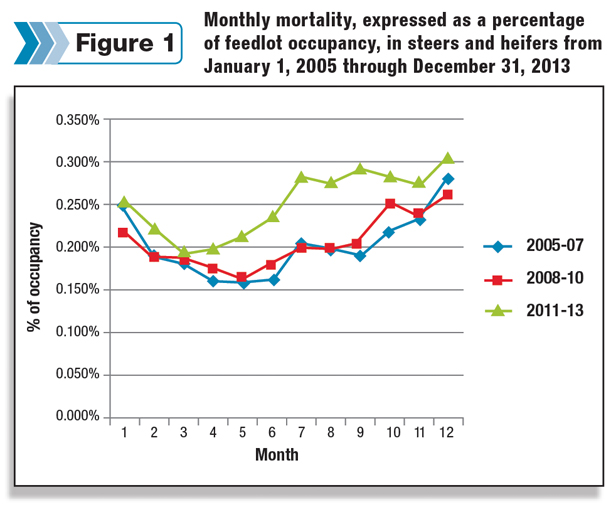

The Vogel study also measured mortality by actual month of death, expressed as a percentage of feedlot occupancy (Figure 1).

Data were measured in three different three-year intervals, but show generally that mortality was lowest from April through June each year, then jumped in the fall and early winter, before peaking during December.

Among the three-year sets, mortality from 2005 to 2007, then 2008 to 2010 saw similar trends, averaging 0.205 percent of feedlot occupancy monthly. But the 2011 to 2013 period averaged a mortality rate of 0.26 percent of occupancy monthly – which was 127 percent that of the rate of the prior six-year period.

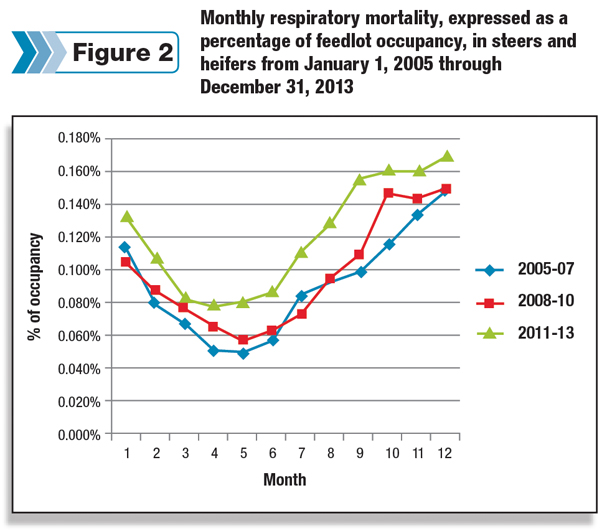

Data for monthly mortality linked to respiratory factors (Figure 2) show cattle vulnerable in the first 60 days, and then with an elevated risk after six months in the feedyard.

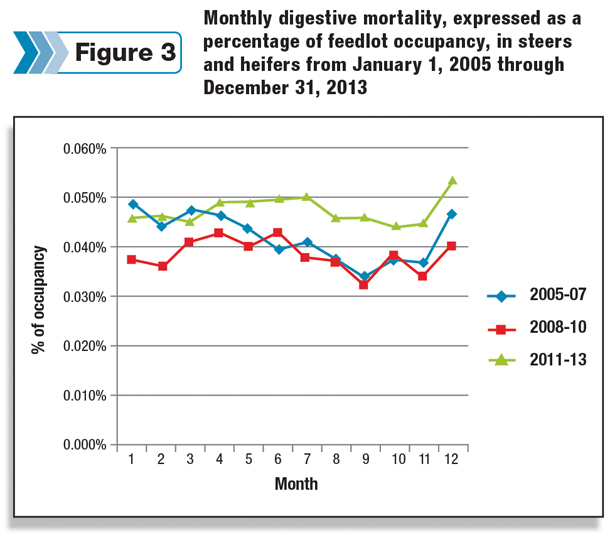

Digestive death loss (Figure 3) saw elevated risks for cattle in the last three-year data set. But for the entire study, peak areas of digestive death loss varied from one interval to another. Average days at death from digestive losses were around 99 days for both heifers and steers.

Digestive death loss (Figure 3) saw elevated risks for cattle in the last three-year data set. But for the entire study, peak areas of digestive death loss varied from one interval to another. Average days at death from digestive losses were around 99 days for both heifers and steers.

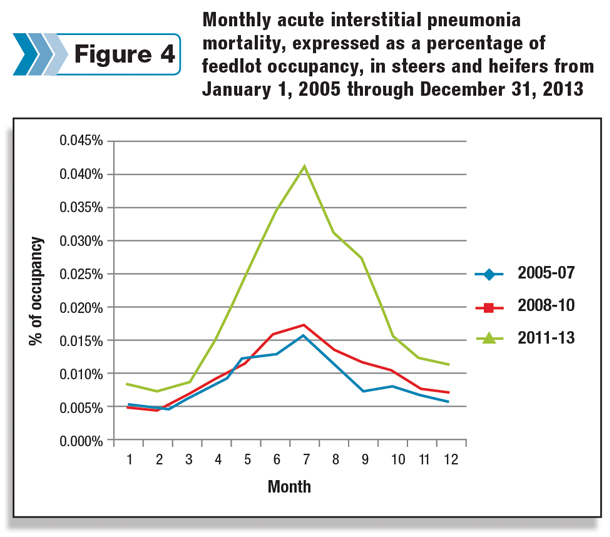

Mortality from AIP (Figure 4) jumped in 2011 to 2013 to 0.019 percent of monthly occupancy – more than twice what it was in the previous six years.

Mortality by placement weight

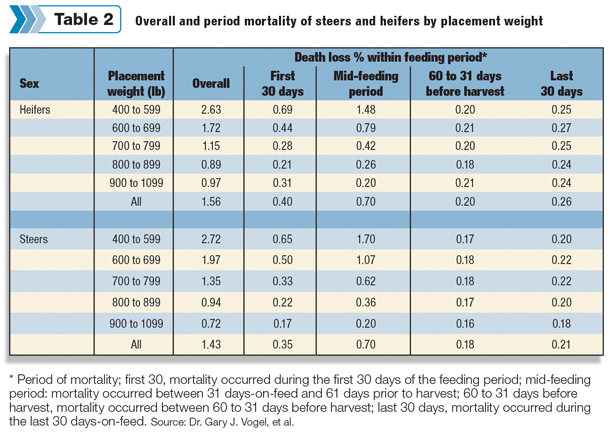

As noted by Pyatt, the Vogel study and its use of Benchmark data clearly found that mortalities were higher in lighter weight cattle for both sexes (Table 2).

Increased bodyweight at placement was associated with reduced morbidity rates. Lighter calves face greater risks of BRD in the first 30 days of feeding, and in the mid-feeding period, the death loss risk goes higher.

Increased bodyweight at placement was associated with reduced morbidity rates. Lighter calves face greater risks of BRD in the first 30 days of feeding, and in the mid-feeding period, the death loss risk goes higher.

For steers and heifers weighing less than 600 pounds at arrival, death loss at the mid-feeding period was 63 percent and 56 percent of the total mortality for steers and heifers, respectively.

For cattle arriving at more than 900 pounds, the percent of death loss at those feeding stages within the total cases of morbidity was only 27 and 20 percent for steers and heifers, respectively.

Pyatt says the data show lighter weights, and an increase in days on feed, contribute to mortality.

“What he was trying to show was that while you’re there on feed, the greater portion of those days are outside of those first 30 and last 30 days on feed, so you have a longer exposure time if that period is longer. That’s why you typically see a proportionally higher death loss during that time frame.”

Explaining the investment

The issue with more days on feed and greater risk on lighter calves, Pyatt explains, is that those animals are typically ones that help feeders make a profit.

“As animals come into feedlots at heavier weights, they typically have a lower risk level for morbidity and mortality. The trade-off there is adding weight to [higher risk] animals is what creates margin for feedyard producers.

Those animals have to be at a cheaper cost than those that are already heavy, because we’re adding less total pounds to those. So we have more fixed costs and less opportunity to dilute those fixed costs over less pounds.”

The study points out that for 2011 to 2013, variables such as drought, limited feedstuffs and poor immunity of calves could all have been at play.

“There’s been an interesting dichotomy seen with the volatility in feeder calves and input costs,” Pyatt says. “Now we’ve actually been selling those cattle at much heavier weights and extending days on feed, in the feedyard phase, and now we’re starting to see penalties and discounts associated with heavyweight carcasses.

So we’re starting to see that pendulum switch, to getting back to less days on feed and, to some extent, maybe a little bit lighter out-weight, trying to minimize those discounts.” ![]()