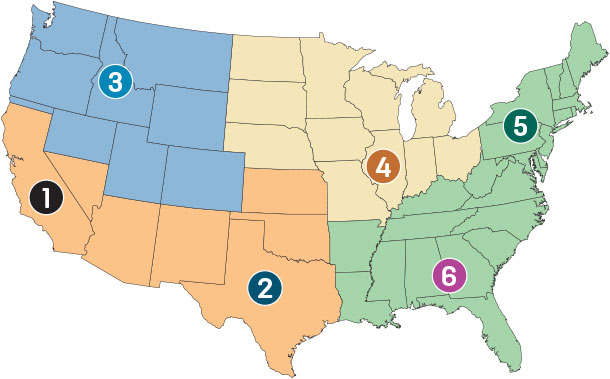

One phrase is repeated over and over again to describe the outlook for dairy producers in 2017: “cautiously optimistic.” Here’s Progressive Dairyman’s regional “State of Dairy” report.

WEST

1. California’s ripples felt throughout the region

As 2017 moves through the first quarter, the outlook among Western dairy producers is somewhat improved, but the challenges are many, according to Bob Matlick and Leland Koostra, with the accounting firm of Frazer LLP. Based in Visalia, California, Frazer LLP’s market area covers California, western Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, eastern Washington and Idaho.

“There is some optimism for 2017 based on current milk futures prices,” Matlick said. “But 2016 was not a great year for dairy in the West, primarily due to low milk prices during the first nine months of the year. Equity positions eroded, although not as bad as 2009 and 2012.”

As the dairy giant, California causes ripples throughout the region. Between water, air and environmental regulations, and labor and credit conditions, “California is finding it tougher to compete,” Matlick said.

“The almond/pistachio/nut boom is over, and real estate values are declining,” he said. The weaker land values have a direct impact on credit availability and beyond, stretching all the way to replacement heifer prices.

Those challenges are shared in many parts of the West, where weakened equity positions, regulations and low milk prices have tightened credit availability for dairy investment, Matlick said. Along with lender consolidation, the low level of return on investment is not matching the risk associated with price volatility, reducing the appetite for growth.

Lack of an available and consistent labor supply is an escalating concern, with dairy producers eager for federal immigration policy reforms.

“Any time you sit down with a dairyman in the West, the discussion turns to labor,” Matlick said. As such, robotic rotary parlors are getting more scrutiny.

The Margin Protection Program for Dairy (MPP-Dairy) is offering little to no income protection for Western producers, and more are looking at other risk management tools.

“The roller coaster of price volatility is creating ‘fatigue’ among Western producers, stemming from a year trying to dig out of the hole of a down year followed by another down year,” Koostra said. “They’re looking for any way they can take volatility off the table. I’ve heard more dairymen talk about giving up the top 30 cents if they can keep the valleys more manageable.”

Precipitation – at times too much, too fast this winter – has improved moisture conditions, but groundwater levels haven’t been replenished for producers counting on private wells.

The precipitation, combined with colder temperatures, has been a double-edged sword from California to Idaho in terms of cow and udder health, cow comfort and production, especially on open-lot dairies.

One new variable is ahead. “We need to be wary of interest rate increases that will weigh on profitability,” Matlick said. “We’ve been in such a low interest rate environment for such a long time, we may have become complacent.”

In some cases, California dairy is on the move.

“If any California producers are looking to expand, it’s outside the state,” Koostra said. “Cow numbers continue to decline. When California cattle are sold, a large number of them are headed to Texas or Idaho.”

SOUTHWEST

2. Texas on the rebound

California’s loss is becoming a net gain in west Texas, where cow numbers have rebounded from Winter Storm Goliath. Recovery is slower in New Mexico, hampered by water supply issues, Matlick and Koostra said.

“Most Texas dairy producers are cautiously optimistic about the upcoming year,” said Joe Osterkamp, board chairman of the Texas Association of Dairymen and owner-operator of Stonegate Farms near Muleshoe, Texas.

In addition to Goliath, milk prices and the uncertainty of the presidential election cast a cloud over 2016.

“With the election and Goliath behind us, mild winter weather, lower feed costs and a rising milk price due to good demand, many producers seem to be looking forward to 2017.”

With one eye on margins, most of the region’s producers have the other eye on the lookout for drought.

“Drought can quickly cause our feed costs to rise due to local feed scarcity. Regardless of irrigation, we need rain to make good crops,” said Osterkamp, noting producers are constantly learning and investing in water-conserving measures.

Some small-scale expansion is taking place, driven by positive margins and still-low interest rates, Osterkamp said. Adding pens or expanding milking parlors seems to be the most common form of expansion as producers seek to maximize the capacity of existing facilities.

The region is also benefiting from processing capacity growth. Osterkamp described several ongoing and completed projects. Lone Star Milk Producers started processing milk in a new plant near Canyon. Select Milk Producers is in the construction phase of a new powder/butter plant in Littlefield.

With a capacity to process up to 4 million pounds of milk per day, that plant is due to open in late 2018. Hilmar Cheese has completed an expansion at its Dalhart facility. Southwest Cheese in Clovis, New Mexico, is in the midst of an expansion.

“From the producer’s view, it is great to see some new homes for our milk that will help boost our local economies while having a positive impact on the monthly milk check,” Osterkamp said.

NORTHWEST

3. A favorable profitability outlook for 2017

Staff with Northwest Farm Credit Services forecast a more favorable profitability outlook for 2017, thanks to improved milk prices and lower feed costs. Most Northwest dairy producers ended 2016 at breakeven, with fourth-quarter profitability offsetting losses during the first half of the year. Favorable weather strengthened milk production per cow.

Offsetting higher milk prices are lower beef, cull cow and bull calf prices. Day-old bull calves, selling for as much as $400 per head in 2014, are now bringing $10 per head.

Replacement cow prices were also showing some weakness, although demand for Jerseys remained steady as some producers were adding Jersey cows to their milking herd to improve milk components and receive quality bonuses on their milk.

Eastern Washington dairying has been mostly business as usual, Matlick and Koostra said, with expansion limited due to environmental regulations.

Idaho expansion continues, but it is occurring farther distances from existing dairy centers due to limited land availability to meet nutrient management requirements and water laws.

MIDWEST

4. Living with a shrinking basis

Many Midwestern producers saw 2016 milk basis – the difference between the futures contract price and the individual “mailbox” price, including quality and volume discounts or premiums – decline slightly from 2015. Regions with excess milk, such as Michigan, continued to see negative basis throughout the year, said Matthew Lange, business consultant with AgStar Financial Services.

“Buoyed by current higher milk prices, sentiment among producers is one of cautious optimism with a slight resolve to prepare for the worst and hope for the best,” Lange said. “As of early February, larger milk checks were providing much-needed cash to keep up with bills. However, to tackle payables or recover the 2, 4 or 7 percent equity lost in the last year, producers will need to find more margin.

“Most producers are in a holding pattern when it comes to longer-term commitments and investments,” Lange continued. “Construction and technology purchases continue to be kept to a minimum. A wave of younger producers seeking to enter the business remains high despite the challenge for farms to find ways to make the generational shift, both operationally and financially.”

In most cases, the outlook for 2017 depends on the state of individual businesses, Lange said.

“There is no doubt that businesses with payables greater than 30 days, high operating loan balances and carryover, and those struggling to make debt payments, are feeling greater stress about financial recovery,” he said.

“There are, however, those operations that have set goals and targets to reduce cost of production, achieve greater reproductive and milk production performance, and limited unplanned expenses who found consolation in limited loss of earnings and cash. This latter group is more optimistic about their success in 2017 and beyond.”

2016 was a tale of two halves: Class III milk prices averaged $13.48 per hundredweight (cwt) in the first half. Producers taking marketing positions and participating in income insurance programs like Livestock Gross Margin for Dairy found some relief. Class III prices averaged $16.25 per cwt in the second half of the year, for a full-year average of $14.87 per cwt, about 93 cents less than 2015.

Along with milk prices, cull cow and bull calf values steadily declined in 2016 with a significant drop-off in the fourth quarter, said Lange. Prices for Holstein cull cows dropped 30 to 40 percent during 2016. Bull calves, once selling in excess of $350 per head, now bring less than $100. In addition to providing much-needed cash, the high cull value had reduced net costs for replacement animals to less than $1 per cwt of milk.

Providing some buffer to lower milk price trends, favorable crop production weather across much of the Midwest provided good yields and quality, resulting in strong feed inventories to start 2017.

“Despite the roller coaster of markets, focus back on the farm has continued to be on maximizing production, achieving efficiencies and reducing costs,” Lange said. “Producers continue to evaluate ways to reduce land rent values, increase income over feed cost, improve labor efficiency, reduce death loss and maximize cull cow values and other cost drivers in an effort to find 5 cents, 15 cents or more per hundredweight in cost of production reductions.”

Elsewhere in the Midwest, a better financial picture is fueling cautious optimism in Nebraska. Higher protein prices are adding to milk checks, and feed costs are reduced thanks to lower prices and excellent supplies, according to Nebraska Extension ag educator Robert Tigner and extension dairy educator Kim Clark. While many dairy farmers are looking into the expansion process, they’re waiting to see if margins hold.

“One major factor impacting expansion decisions is the lack of trained employees,” Clark said. For that reason, robotic milking is getting closer scrutiny, allowing producers to devote more time to farm management, animal care and feed quality, and less on training employees.

NORTHEAST

5. Marketing challenges growing

In the Northeast, milk prices are likely to increase in 2017, providing improved margins. However, finding a home for milk continues to be a challenge with supply exceeding regional demand and processing capacity, according to Chris Laughton, director of Knowledge Exchange with Farm Credit East.

While domestic consumption is higher for cheese, yogurt and butter, consumption of fluid milk continues a downward trend and is one-third less than it was 40 years ago. This has been a particularly significant factor in the Northeast market, which relies heavily on fluid consumption. If improved margins in 2017 provide further incentives to increase milk production, the disconnect between what’s demanded and what’s produced will widen.

“Over-order premiums to producers are being reduced,” Laughton said. “Some producers are receiving deductions or a loss of their markets entirely. Dairy farmers may no longer be able to grow without regard to overall market demand and processing capacity. During 2017, we will continue to see Northeast processors, cooperatives and other market participants scramble to find homes for surplus milk.”

Alan Zepp, risk management program manager at Pennsylvania’s Center for Dairy Excellence, echoed those sentiments. Producers are cautiously optimistic as prices improve, but they still have concerns.

“The milk tanks taking in the milk supply from the mid-Atlantic and Northeast have been full and occasionally spilling over for the past two years,” Zepp said. “The industry expects this to continue as it adapts to the declining fluid milk consumption. Matching farm supply to the current processing capacity continues to be a challenge.”

Much of central Pennsylvania managed around a dry crop year last summer, which raised the corn basis and feed costs east of the Allegheny Mountains. The milk basis is falling due to the increased marketing costs associated with the strong milk supply. The net result is that margins are recovering slowly.

“Pennsylvania is not seeing many large expansions as environmental and labor issues are also weighing on the industry,” Zepp said. “Dairymen in the commonwealth are in business for the long term, but today they are emphasizing on becoming more efficient and profitable.”

SOUTHEAST

6. Milk production declining, becoming more concentrated

“Historically, Southeast dairy farmers react quicker to changes in milk prices, be they increasing or decreasing,” said Calvin Covington, retired dairy cooperative CEO. With 2016 mailbox prices in the Southeast averaging about $1.75 per cwt lower than in 2015, milk production took a 2.6 percent hit. Of the 10 states in the region, only Georgia produced more milk in 2016 than the year before.

Dairy farmers reported increased costs in other areas negated much of the savings in feed costs.

Covington highlighted three regional trends, all of which were amplified in 2016.

- The Southeast is catching up to the rest of the country in milk production per cow. “Since 2010, milk production per cow in the Southeast has increased about twice the national rate,” he said.

- Fewer dairies are responsible for the majority of the milk production. “It is estimated about 75 percent of Southeast milk production is produced by only 30 percent of the approximately 2,500 Southeast dairy farmers.”

- Southeast milk production is becoming more concentrated. “In 2000, only 32 percent of the milk was produced in Florida and Georgia. Last year, it was 47 percent. Since 2010, milk production in Florida and Georgia has increased 18 percent and 31 percent, respectively.”

Two major challenges face the Southeast dairy industry: declining fluid milk sales and shrinking over-order premiums.

“About 75 percent of Southeast milk production is utilized in fluid milk, compared to only about 25 percent nationally,” Covington said. “Since 2010, fluid milk sales by plants in the three federal orders covering the Southeast has declined at an annual rate of about 2 percent."

"This equates to a loss of about 1.5 billion pounds in fluid sales from 2010 to 2016. During the same time period, milk supply increased about 500 million pounds.”

There are dairy farms wanting to expand and people interested in building new dairies in the Southeast. However, there are not sufficient local markets to handle additional milk. Milk buyers hesitate on adding new producers due to declining fluid demand.

That puts pressure on over-order premiums, which no longer cover the expense to serve a fluid milk market. Milk not needed for fluid incurs additional cost to find a manufacturing market, and most manufacturing markets receiving surplus milk from the Southeast pay below federal order class prices, Covington said.

“For many years, it was common for mailbox prices in three Southeastern orders to exceed the order blend price,” he said. “Now, mailbox prices are $1 per cwt or more lower than blend prices. The future growth of the Southeast dairy industry is dependent upon having sufficient local milk markets to utilize local milk production.”

The good news is that some cooperatives are starting to work together to address the challenge of insufficient local markets and over-order premiums, Covington said.

Echoing the other regions of the country, Southeast dairy producers are “cautiously optimistic” entering 2017, according to Farrah Newberry, executive director of Georgia Milk Producers Inc. “Budgets will remain tight this year, but current indications are: Margins should be significantly larger. Many dairy producers will use the projected price increase to ‘stop the bleeding’ of their business’s bottom-line,” she said.

“For smaller dairies near larger cities, urban encroachment has been a concern for many years,” Newberry said. “Those dairy producers are struggling to plan for the long term, and they will be faced with the decision to relocate or go out of business within the next five to 10 years. Since January 2015, Georgia lost over 15 percent of our dairy farms.”

Many mid-size and large farms were able to squeeze margins and weather the low milk prices last year. More cows were added, and milk per cow increased.

“Transportation issues and movement of milk to manufacturing plants due to the loss of fluid milk consumption continues to be a big issue for the Southeast,” Newberry said. “Dairy cooperatives are currently taking the position that dairies in the Southeast should not expand or add cows. Producer associations and cooperatives are exploring the possibility of constructing a manufacturing facility in the Southeast.”

With growth opportunities minimized, large-herd dairies will be focusing on fine-tuning operations.

“The current labor force shortage and future immigration legislation are top concerns for these dairies,” Newberry said. “Animal welfare and environmental issues continue to worry dairy producers as well. Producers remain hopeful that feed prices will stay low and that they can add back to their equity.” ![]()

-

Dave Natzke

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Dave Natzke