Tired of waiting for mastitis culture results to come back and, when they do, the result is “no growth”? About 40 percent of clinically abnormal milk samples tested with traditional bacterial culture come back with a “no growth” result, often leaving dairy producers right where they started – with a mastitic cow and no diagnosis for accurate treatment.

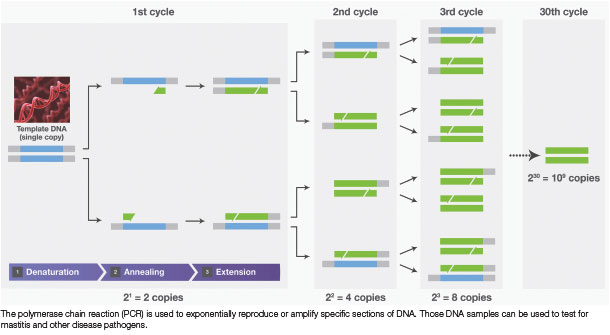

As an alternative, mastitis results generated using PCR are complete in three hours or less, and veterinarians and producers are provided a highly accurate positive or negative outcome with low levels of false positive or false negative results.

“PCR doesn’t require a viable organism, and that’s the key difference versus culture. Whereas with culture, we are trying to isolate and grow the infectious agent, which presents several challenges,” says Colin Lindsay, a practicing and consulting veterinarian based in Cumbria, United Kingdom.

“For bacterial culture, first we must sample in an aseptic manner, then transfer the sample to the lab, which has the inherent problem of time delays that are critical with some pathogens. Often, we’ll use specific transport media to preserve those organisms, but they must be in the practice and ready to go.

Upon arrival at the laboratory, samples must be handled carefully and plated in specific growth media to increase the odds of growing the organisms.”

Another advantage of PCR is: It allows a producer or veterinarian to perform tests on cows that have already been treated with antibiotics.

“You wouldn’t even contemplate trying to culture a milk sample from a cow that’s already been administered antibiotics,” Lindsay says. “However, PCR still provides the option to diagnose that cow.”

A third benefit is the flexibility to store samples. For example, if collecting a sample on a Friday night, Lindsay can store PCR samples over the weekend in his practice’s refrigerators, or even freeze them, and then send them to the diagnostic lab on Monday morning.

“In that scenario, we can still get a result with PCR. Whereas this would not really be possible with a culture because it must be a recent, fresh sample,” he says.

PCR can be used with individual cow samples or bulk milk samples which can be fresh, frozen or preserved.

When it comes to testing for mastitis, especially Mycoplasma bovis (M. bovis), which can be very difficult to culture, PCR testing is particularly important. Since it is a slow-growing pathogen, testing for M. bovis using culture testing can take up to 10 days for results to be read.

When the diagnostician views the culture plate, it may be overgrown with other bacteria, making it difficult to recognize whether the pathogen he or she was looking for has grown.

“M. bovis is a very delicate organism and has to be handled with care,” Lindsay says. “Culturing M. bovis is difficult, but PCR will have a dramatic impact on the diagnostic rates. A trial in Ireland demonstrated a fivefold increase in diagnosis of bovine bacterial pneumonia when they started using a PCR test compared to culture.

The principle is the same for mastitis; a more specific test will provide more specific results.”

Advantages of faster results

Like any disease, the quicker a mastitis diagnosis is determined, the faster a veterinarian and farmer can develop an action plan.

“If we know the bacterium involved, we can drill down into our antibiotic therapy for that specific bacterium,” Lindsay says. “In this day and age of antibiotic reduction, this is critical. For example, E. coli infections may have treatment protocols reduced or stopped all together upon confirmation of a diagnosis.

A chronic Staphylococcus aureus infection, on the other hand, might have the treatment protocol extended or that cow culled. With the development of mastitis vaccines in the United Kingdom and Europe, a specific diagnosis is becoming even more important in the management and control of mastitis pathogens.”

Globally, treatment protocols vary by country. Generally, there are first-line (broad-spectrum) and second- and third-line (more tailored) antibiotic protocols which are determined by test results.

In certain Europe member states, like the Netherlands and Denmark, there are clearly defined protocols outlining which antibiotics can be used. In these and other member states, antibiotics can only be used once there is confirmation of a diagnosis, so speed is of the essence, Lindsay notes.

“Interestingly, the diagnostic submission rates in these countries significantly increased because of these control measures on antimicrobial usage,” he adds.

Antibiotic susceptibility

When considering a pathogen’s susceptibility to antibiotics, Lindsay looks at resistance patterns.

“Historically, we didn’t think gram-positive pathogens had developed much resistance, but Staph aureus now has,” he says. “As for gram-negatives, E. coli certainly has resistance patterns – the reality is: That’s probably true for all of them.

That’s where the debate is the strongest – is it best to treat those gram-negative infections with antibiotics or not? Or if we do, are we just creating a bigger problem?”

As for M. bovis, it’s often underdiagnosed and is not a routine pathogen veterinarians or farmers test for because culture is very difficult. A diagnosis of M. bovis mastitis means culling rather than treating, or at a minimum, isolating the cow or group of infected cows from the rest of the herd.

“It depends what stage of the outbreak you are in. If you’re at the very tip of the iceberg, and you’ve got one or two animals that are M. bovis-positive, I’d recommend culling to save yourself the grief of having to worry about isolation and separate milking groups,” says Lindsay.

“However, if a large percentage of your herd are M. bovis-positive, then it may not be economically possible to cull. In this case, you would manage that group of cows as a completely separate entity and manage your way out of the situation.”

Interpreting no-growth results

“A no-growth result, which occurs about 40 to 50 percent of the time, is simply a fact when you submit milk samples for bacterial culture,” says Lindsay. “As a veterinarian, the problem is trying to explain it to farmers. In their eyes, that’s seen as a failed sample. This is not necessarily the case, but it gives a poor perception of the technique.”

A no growth simply means the culture grown didn’t identify the pathogen, but the mastitis could be caused by a variety of issues, including:

- A gram-negative pathogen

- An intermittent Staph aureus shedder

- Mycoplasma which was so delicate it didn’t survive transport to the laboratory

To reduce the number of no- growth results, Lindsay recommends reviewing sampling techniques but says for high-value cows, he also suggests switching to a PCR test.

“If you can use a PCR test, then it’s not necessary to rely on viable organisms – we’re just sampling for pathogenic DNA – it will have a dramatic effect on the no-growth rate,” he says. “With culture, you’re always playing the odds game and hoping you’re right.

That’s where PCR is a game-changer because you can be confident in the result. PCR technology is constantly advancing. The new testing protocols are more streamlined and easier to interpret. If you are struggling with a mastitis problem, it is definitely worth revisiting.”

Even though PCR is generally a higher initial cost, Lindsay says in his experience, farmers don’t mind paying the extra cost if they know they’re going to get a result.

“The most expensive test is the one that comes back inconclusive – with no interpretation,” he says. ![]()

PHOTO: Photo courtesy of Thermo Fisher Scientific.

-

Christina Boss

- Senior Global - Product Manager Dairy Solutions

- Thermo Fisher Scientific