It’s impossible to assess the rumen pH of a dairy cow just by looking at her. Yet, impaired rumen digestion can be silently lowering herd production and health.With careful observation, there are subtle signals normal rumen function may be disrupted.

Picking up on these hints can make significant improvements in an operation’s profitability. It’s simply a matter of tuning in to the signals the herd is giving you.

The modern dairy cow

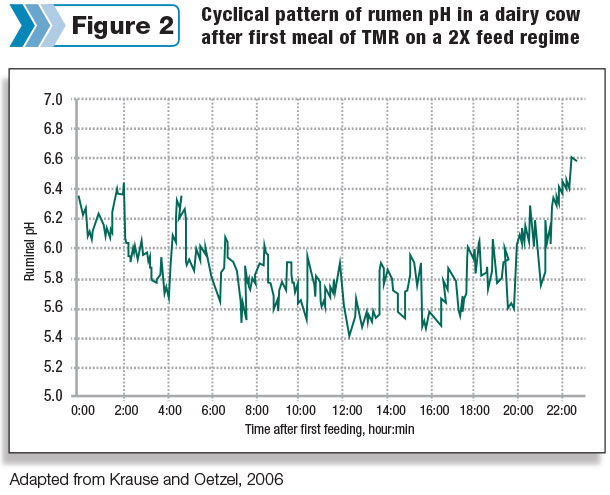

For the modern lactating dairy cow, it’s not unusual for her to cumulatively spend up to 11.8 hours per day with a rumen pH below 5.8, which can mean nearly half a day of impaired digestion. The time spent below a pH of 5.8 for more than a three-hour duration is known as subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA).

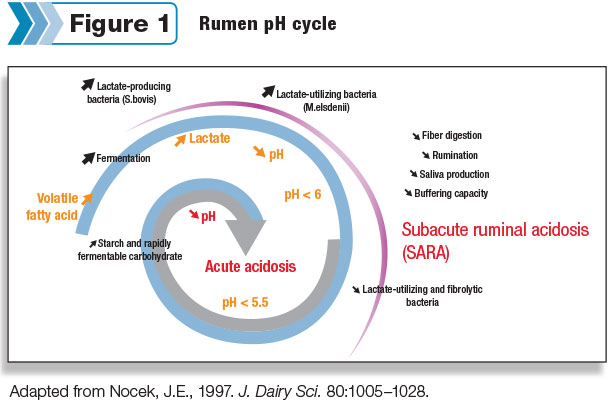

After a meal, volatile fatty acids can accumulate in the cow’s rumen fluid and will lead to a lower rumen pH. If rumen pH is slow to recover back above 5.8, it can lead to a bout of SARA. Lactating dairy cows can take six to 10 meals in a 24-hour period. This naturally leads to a fluctuating pH throughout the day (Figures 1 and 2).

This problem can occur surprisingly often and silently affect production. SARA can lower herd performance by an estimated $1.12 per cow daily and is estimated to affect 10 to 40 percent of dairy cattle – making it recognized as the most important nutritional issue of dairy cattle on a herd basis.

The costs of SARA range from lower milk yield and reproductive performance to less efficient use of feedstuffs and ongoing secondary health challenges, which can lead to increased voluntary culling rates. Yet if we listen to what the cows are telling us, we can stop the effects of SARA before they start.

Types of SARA episodes

SARA episodes can be either sudden-onset or recurrent. Sudden-onset SARA episodes are short durations of time generally associated with the consumption of large quantities of rapidly fermentable carbohydrates. This shifts the microflora in the rumen and creates an environment where lactate-producing species, such as Streptococcus bovis, can proliferate.

Recurrent SARA can result in long-standing effects in the rumen, organ and skeletal systems, hoof-related disorders, clinical illness and even death. Recurrent SARA can cause rumen wall erosion that can lead to bacteria entering the bloodstream. From the bloodstream, bacteria travel and cause liver abscesses and damage to the heart, lungs or joints.

Laminitis, overgrown hooves, septic arthritis, abscesses and ulcers of the sole are all associated with recurrent SARA. It can be difficult to connect recurrent SARA episodes to hoof-related conditions, as they often occur months after the initial SARA episodes and persist for a long time.

Researchers estimated that each case of SARA-related laminitis cost the dairy producer around $302, and 15 percent of cows culled for slaughter are culled due to laminitis.

Tuning in to the signs

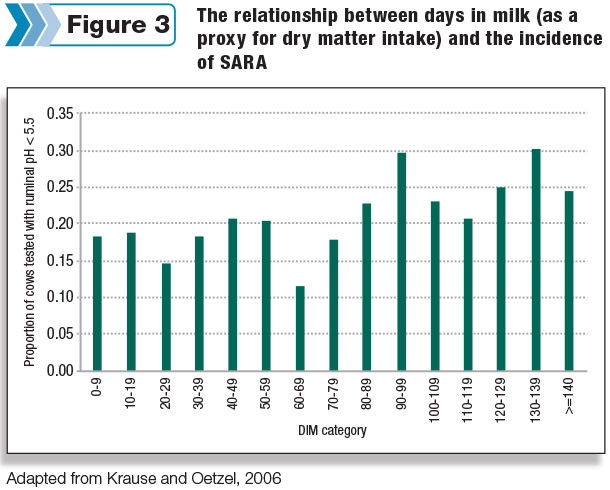

The most at-risk groups for SARA are fresh and high-yielding cows (Figure 3). It’s particularly important to monitor these groups for signs of SARA. However, most dairy cattle don’t exhibit overt signs of SARA. Commonly, cattle will eat more sporadically or even reduce their feed consumption. However, the subtle individual behavior can go unnoticed in commercial herds.

The time delay between a SARA episode and overt signs make the problem difficult to pinpoint. Other signs of SARA include:

- Decreased and variable dry matter intake

- Reduced cud-chewing

- Mild diarrhea or inconsistent fecal texture

- Foamy feces containing gas bubbles

- Change in fecal color

- Excretion of partially digested feedstuffs such as long forage fibers or visible, whole cottonseed

- Soil or concrete licking

- Excess free-choice salt intake

- Poor body condition

- Reduction of milk component yield and component yield inversion

- Increased incidence of gram-negative mastitis

- Lameness

- Reduced conception rates

Historically, the most accurate analysis of SARA involved taking a ruminal fluid sample collected by rumenocentesis. While a “gold standard,” this method of measuring rumen pH is impractical and expensive for routine use on commercial dairy farms.

The use of wireless rumen pH boluses shows more commercial promise, although the cost per cow is still expensive in relation to the lifespan of the bolus. Currently, it’s more practical to evaluate risk based on ration analysis, management and identification of cow signals and herd health.

SARA solutions

SARA persists despite the adoption of TMR and in-feed dietary buffers like sodium bicarbonate. Feeding high-forage rations will not necessarily avoid SARA either. The majority of forage in TMRs is corn silage, which contains about 0.4 pounds of kernel-processed high-moisture shell corn per pound of corn silage dry matter – making SARA a real danger even with higher-forage rations.

Sound TMR mixing and delivery procedures in addition to excellent feedbunk management of a correctly formulated ration may help protect the entire herd from experiencing the consequences of SARA.

However, a TMR that is too dry (greater than 50 percent dry matter) may allow cows to preferentially sort for grain components and skip forage particles. In addition, feeding unstable or moldy feeds can further threaten rumen function and performance.

Producers should pay particular attention to the amounts of forage fiber and non-forage fiber sources in the diet. Ensuring that added long-stem forage fiber (hay or straw) is the correct length (1 to 2 inches for mature dairy cows) can help minimize the effects of slug feeding and sorting of the diet.

When SARA occurs, however, rumen function isn’t optimized to make the best use of any ration. Even the routine use of in-feed dietary buffers such as sodium bicarbonate, while useful, cannot alone eliminate the risk of SARA.

Probiotic feed additives can help improve rumen function and increase fiber digestion. For example, a rumen-specific strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been shown to help maximize rumen function in all life stages of dairy cattle.

In fact, research has shown cows fed an active dry yeast specifically selected to maximize rumen function spend significantly more time above the SARA threshold and even produce 2.1 pounds more per day of 3.5 percent fat-corrected milk per cow per day.

Under heat stress, a higher feeding rate of this strain of S. cerevisiae resulted in more efficient level of production. In fact, this strain of active dry yeast received a functionality claim from the FDA which states that supplementation with yeast can “aid in maintaining cellulolytic bacteria population in the rumen of animals fed greater than 50 percent concentrate.”

By listening carefully to the signals your herd is sending you, producers and nutritionists can help the modern dairy cow maintain a more consistent rumen pH. In turn, we’ll allow the rumen to function more effectively – making the best use of the dynamic microbial environment and management strategies in place. PD

References omitted due to spacebut are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

-

Tony Hall

- Dairy Technical Service Manager

- Lallemand Animal Nutrition, North America

- Email Tony Hall