You might be surprised to know that harmful pathogens often lurk in fermented forages like haylage and corn silage, causing health and productivity issues when consumed by dairy cows.

In fact, a recent survey of feed samples from across the U.S. found that over half of corn silage samples and eight out of 10 haylage samples tested positive for clostridial bacteria.

Prevalence of pathogens in forages

To document the level of pathogens found in U.S. forages, researchers at Arm & Hammer Animal and Food Production collected 866 corn silage samples and 577 haylage samples from 457 dairy herds across 27 states in the Upper Midwest, South-Central, Southeast, Northwest and West regions. Samples were collected from February 2016 to December 2019, reflecting a range of growing conditions across multiple seasons.

Test results showed that 83% of the haylage samples and 57% of the corn silage samples tested positive for clostridia. The higher incidence of clostridia in the haylage samples was likely caused by dirt contamination during harvesting. Plus, the generally lower pH of corn silage versus that of legume forages inhibits clostridial growth.

Clostridia load is measured in colony-forming units per gram. Any level above 100 colony-forming units per gram is cause for concern. Testing showed that one-quarter of the corn silage samples and one-third of the haylage samples had high clostridia loads at or above 100 colony-forming units per gram. Up to 7% of the samples had extremely high loads above 1,000 colony-forming units per gram – indicating potential for severe reductions in health and productivity.

Researchers also tested 2,760 total mixed ration (TMR) samples, and nearly all (93.8%) contained clostridia. The higher level compared with forage samples likely resulted from bacterial growth during mixing and feeding.

The predominant strain of clostridia found in feed testing was Clostridium perfringens, representing 64% of the samples. C. perfringens Type A is often implicated in hemorrhagic bowel syndrome (HBS), and even subclinical levels can cause cows to go off-feed and reduce their milk production.

Testing also revealed presence of non-toxigenic C. butyricum, as well as C. bifermentans.

When present in ensiled forages, these clostridial bacteria can produce undesirable byproducts, including butyric and acetic acids that can create intake problems and rumen health issues in dairy cows.

Whole-farm pathogen control

To limit your herd’s exposure to C. perfringens and other harmful pathogens, it’s important to take a whole-farm management approach that includes proper silage management and manure handling, along with good hygiene across all areas of the operation.

Controlling disease-causing organisms found in the dairy environment begins with an understanding of the pathogen cycle. Pathogens that may exist in a cow’s digestive system are excreted into the environment through her manure and remain in the pit or lagoon until spread on fields. During manure application, it’s possible for pathogens to then contaminate the growing crop. As the cow consumes that crop, either through grazing or by eating ensiled forage, the pathogens return to her system, and the cycle starts again.

Proper silage management

Controlling pathogens in forages starts with proper silage harvesting, packing and storage. Be aware that clostridial bacteria exist everywhere in the environment, including soils. If heavy rains cause soil to be splashed onto plants just ahead of harvest, a heavy load of clostridia may be harvested along with the forage.

To achieve good packing and fermentation, be sure to harvest at the proper maturity and moisture and chop at the right length for your type of storage. Fill the silo as fast as possible; use a bacterial inoculant and cover. After opening the pile or bunker, be sure to feed out at the proper rate to stay ahead of air penetration into the face.

To study variability in silage quality and pathogen contamination, Arm & Hammer researchers took weekly face samples from a corn silage bunker in Wisconsin over a six-week period. Testing found significant variation in clostridia counts, including several “hot spots” with levels as high as 7,300 colony-forming units per gram. Uneven distribution of clostridia loads within the bunker may have been due to differences in packing densities, leading to oxygen exposure, or caused by soil contamination during harvesting.

Achieve fermentation goals

The goal of silage fermentation is to quickly reduce pH to less than 4.0 for corn silage and less than 5.0 for haylage. Meeting these target pH levels will stop plant respiration and inhibit spoilage bacteria, as well as inhibit clostridia that are sensitive to low pH.

Silage inoculants can help improve fermentation efficiency and aerobic stability in the storage structure. In addition, beneficial bacillus subtilis bacteria strains can reduce both toxigenic and non-toxigenic clostridia in forages. Decreasing the load of clostridia consumed by the animal will help ensure a healthier rumen and fewer off-feed events.

Selecting bacterial inoculants

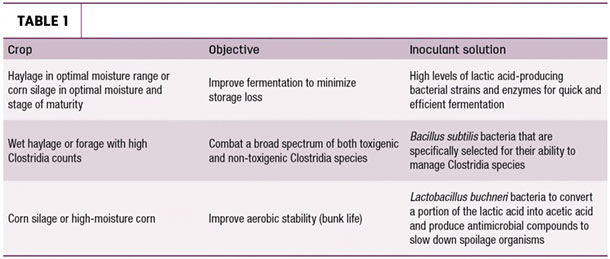

When selecting a bacterial inoculant, be aware of your objective and the type of crop you are ensiling. Always store water-soluble inoculants in a cool place and calibrate inoculation equipment. Use Table 1 as a guide.

Conclusion

When it comes to pathogen control, it’s important to take a whole-farm approach. Manage the dairy environment to limit animals’ exposure to harmful pathogens at every step of the operation, including proper forage harvesting, storage and feedout management.

For more on controlling pathogen loads on your dairy, see “Whole-farm pathogen control starts with calves” by Gene Boomer, “Control pathogens that silently steal productivity” by Joel Pankowski, and “Is manure spreading disease-causing pathogens on your dairy?” by John O’Neill.