Semen sales are increasing each year; yet, if you’d ask anyone related to the industry how our business is doing (producer, scientist, A.I. rep, classifier, breeder), you are likely going to get a mixture of reactions. You may get anything from “on the verge of collapse” to “better than ever.”

The industry seems to be stirring, and it feels uncomfortable. Is our A.I. industry OK?

It would be great if this question could be answered factually, but that is an illusion. Like I said, the answer will likely be different depending on each person’s individual position in the industry. But what we can do is look at several developments and angles and try to understand some of what is going on.

Big is getting bigger

A major development in the U.S. A.I. industry no one will have missed is consolidation. We have seen company A buy company B a few times in a row now. Big companies are getting bigger by mergers and acquisitions. Though relatively new to our industry, this is not an extraordinary development if we look at other industries. In late November, Louis Vuitton bought Tiffany & Co. Louis Vuitton also owns Moet, Christian Dior and Dom Pérignon. In fact, if you Google the LMVH company, which is the official name, you will be astonished at the number of luxury brands which fall under this one enterprise.

Consolidation is a strategy for growth, mainly selected to fuel revenue and earnings. Semen is a relatively low-margin business, and staying ahead of the game in a saturated market means there is a need for diversification. However, diversification requires data, research and biotechnological advances, and all of those require capital. Consolidation prevents stagnation. Bigger companies have more money to fuel longer-term initiatives for higher-scale revenue product development. Plus, there is an instant gain of market power.

Drawbacks, however, are a lack of flexibility (bigger ships are harder to steer) and difficulty to create company synergy quickly enough. It’s too soon to judge the consequences of the consolidations in our industry, but the pressure for diversification likely means we shall see more businesses following this strategy before reaching an equilibrium, and this probably doesn’t stay within U.S. borders.

Breeding programs are becoming more closed

While the A.I. companies are growing, the nucleus breeding programs are becoming more closed. Where it was a business to try and breed the next breeding bull just 10 years ago, it has become very difficult to still be in that business today. The use of advanced reproductive technologies has widened the genetic lag between nucleus elite breeding animals and commercial animals.

Elite females are simply not available anymore outside of company-owned breeding programs. Where genomic selection has removed the need for progeny test programs, the amount of money invested into breeding programs hasn’t decreased. The incredible speed of genetic progress and race for the top bull costs enough money to want to protect proprietary genetics. The closing of a breeding program allows that protection as well as the increase of control and efficiency.

However, in synergy with the growth of companies, the closing of breeding programs also creates more uniformity between sire stacks offered by the A.I. companies. In the end, most A.I. bulls will come from the same “nest” despite being branded differently.

It is very likely this development will create a counter-movement where individual breeders will find an outlet to sell lower-ranking, yet a more diverse portfolio of A.I. bulls. This may not grow into the genetics that are behind the main dairy brands in retail stores feeding the U.S. population. However, it can offer a passionate platform that creates balance and discussion. This will be required for the continuous improvement U.S. dairy cattle genetics need to keep the number one global position.

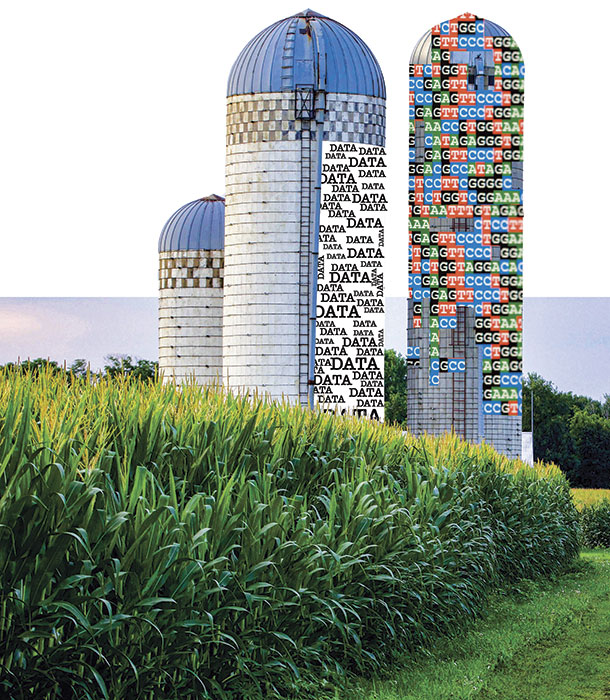

Data is in a silo

What is not measured cannot be changed. Any quantitative geneticist will tell you this. Whatever it is that genomic selection has given us, it wouldn’t have happened without the availability of phenotypes. One of the reasons the U.S. could exploit genomic selection so quickly was the incredible volumes of data it had gathered throughout the years through programs run by NDHIA and the USDA. But the collection of phenotypes has become complex. For one, the traits that are getting relevant are much harder to measure.

Feed efficiency is a classic example. Feed costs are 50% of the total costs on a dairy farm. No one would therefore dispute the economic relevance of breeding for cows that convert 1 pound of feed into more pounds of milk. But measuring feed intake is expensive due to the accurate technology required. Current collected datasets in North America are yielding low reliabilities, and more data collection is needed, but who picks up the bill? The producer, the dairy industry or the USDA? The research conducted by USDA scientists has been essential in the success of U.S. dairy cattle genetics.

Today, they will tell you that access to non-proprietary data is difficult, and the lack of it is threatening the progress of genetic advancement for all. Most complex data currently collected is through the A.I. industry, perhaps in partnerships with universities that have research herds. Although used for research that will benefit the U.S. dairy farmer, it is proprietary and will therefore likely be provided as a service or product with the accompanying charges.

However, without help by the USDA or incentive for dairy farmers to collect such data, the question is: How could it be done otherwise? The sheer magnitude of data used to close the gap from phenotype to genotype on traits such as feed efficiency may be of such expense that only the corporate businesses are able to provide it.

In addition to the availability of data, there is also a large need for skilled people to be able to process it. With the entrance of data giants like Google, Microsoft and Amazon, data scientists can have their pick of very highly paid jobs. The cattle genetics industry is for a large part weighed down by its solid but traditional data platforms. It will take a large investment to move those platforms into the current century and beyond. Again, it will likely be the larger A.I., or biotech, companies that are the only ones which have the funds to do so.

New trends finding their place

The adoption rate of genomic testing and the unfavorable milk market in recent years have been major drivers behind the increase in use of sexed semen and beef. It has been remarkable how much the change of semen usage has impacted the industry. While new providers have recently been added, the sexed semen market is still largely determined by one company, and the profit margin of sexed semen is considerably lower than conventional semen. In addition, beef semen is typically sold for a much lower retail price and by many more players, which again impacts profitability of A.I. companies that have so far mainly focused on dairy.

Management of replacement heifers with strategic use of semen will always be subject to the supply and demand of heifers. More use of sexed and beef means fewer available heifers and a higher price of heifers which, in turn, will lead to a bigger supply and thus less use of sexed semen – and so forth. As with other technologies, sexed semen is here to stay and likely beef-on-dairy as well. We can, however, expect a more maturing market in coming years where more companies supply sexed semen opportunities and the product becomes routine rather than exclusive.

The large influx of beef products originating from beef-on-dairy animals into the beef supply chain has created considerable competition for the pure beef breed segment. You could argue this is positive for the end consumer, as it most likely leads to an improvement of beef quality. How beef-on-dairy will develop is largely dependent on the future milk market as well as any future export of live cattle, which is hard to predict in the current political climate.

Genomic young bulls have been around for 10 years. Despite the advice of geneticists to always use a spread of genomic and proven bulls, the popularity of top-ranking, extremely young bulls has been significant. Now that daughters of these herds are milking, there is some sense of displeasure about the lack of uniformity. It isn’t unthinkable that we will see a trend to revert to a higher usage of proven bulls, to a point where a balance is reached between early prediction and proven performance.

Increase of custom collection and ‘backyard’ semen sales

There is a part of the U.S. A.I. industry that is unquestionably doing well: custom collection. The production centers in the country that offer the service of housing bulls and processing semen are busy. Both the beef and dairy side of the industry are asking for more custom collection, which is a combined effect of growing A.I. companies and the individual breeder segment. From a semen collection point of view, you could therefore argue that the business of selling semen for A.I. is in great condition.

Alongside the larger A.I. companies are smaller businesses that produce and sell semen. A new (relaunched) category to this list are the semen sales between commercial dairy producers that have been termed “backyard” semen sales. This goes back to the previous paragraph where bulls offered by breeders can be attractive competition for those sold by large A.I. companies with almost predictable pedigrees. Having more businesses produce and sell semen is not a development restricted to domestic sales. Even exports to EU and China are now conducted by individual breeders that were once selling bulls to A.I. and are now collecting and marketing their own semen.

While this is a logical development, it is very important to note the U.S. A.I. industry has gotten where it is today through several support programs that have allowed companies to produce and market semen in a safe and monitored way. While other large countries are still developing animal recording programs, the collaboration of U.S. A.I. companies has prevented animal disease from wrecking its industry by precise tracing of animal movements.

Where the USDA prevents live cattle from crossing state borders, it does not have regulations in place that restrict the interstate transport of germplasm. It is by the industry’s own monitoring programs that both domestic dairy farmers as well as international farmers using U.S. genetics are protected. Production centers that participate in the CSS (Certified Semen Services) program have access to many export markets. It is therefore of importance that any individual breeders getting into the business of collecting and marketing semen consider the protection of their semen quality. It cannot be that we end up in a situation where U.S. dairy farmers are protected less than international customers that import U.S. genetics.

So where does that leave us?

It is nearly impossible to diagnose the current state of our A.I. industry. However, what is clear is that it is changing. Give it another 10 years, and our industry will have yet a different face.

For many, this change will be undesirable; for some it will be beneficial. It will be largely driven by technological advances and economic developments, which are unlikely to be stopped. Just as frozen semen, (genomic) breeding values, embryo transfer, sexed semen and genomic testing have changed our industry, so will the introduction of genome editing and precision (smart) dairy farming. There will likely be a counter-movement with the return of smaller cooperatives and private breeders. One will have to find the space he or she finds most comfortable, but we need to be careful that we do not reintroduce the disadvantages of earlier times.

There were good reasons for the creation of programs such as CSS, NDHIA and the national genetic evaluation system. While countries such as Russia and China are trying to set up these programs to become a mature dairy industry, we should not take them for granted. In our transformation, we need to hold on to those factors that made the U.S. a strong genetics industry to start with. If we do, the U.S. A.I. industry may look different, but U.S. genetics remain the best the world has to offer. ![]()

ILLUSTRATION: Illustration by Corey Lewis

-

Sophie Eaglen

- International Program Director

- National Association of Animal Breeders, Inc./Certified Semen Services Inc.

- Email Sophie Eaglen