Rotational grazing methods that have only one grazing event on individual pastures during the growing season provide opportunities to annually alter when grazing occurs.

Four principles of grazing management

When developing grazing management plans on specific pastures, it is important think about the four main principles of sustainable grazing management: appropriate stocking rate, kind and class of livestock, proper distribution and time of the year when grazing occurs.

1. Stocking rate is the number of animals that can be carried on a given area of land for a given period of time.

2. Kind and class of livestock is often determined by the goals of the livestock operator, but diversification – or multi-species grazing – may improve grazing efficiency based on variable dietary preferences of different types of animals.

3. Proper distribution is affected by topography, distance to water, vegetation characteristics and livestock’s ability to efficiently utilize the pasture.

Large distances from water and rough topography can hamper the distribution of livestock throughout the pasture and reduce the amount of forage logistically available for livestock. Poor distribution of livestock increases the risk of localized overgrazing.

4. Timing of grazing represents the time of year or, more appropriately, the phenological stage of plant growth, when grazing occurs.

Time when grazing occurs is one of the management tools directly in the manager’s hands on a year-to-year basis with rotational grazing methods.

The majority of available research has shown setting an appropriate stocking rate is the most important tool in sustainable grazing management. However, understanding and manipulating the timing of grazing can also have significant impacts on forage production.

Effect of time of grazing

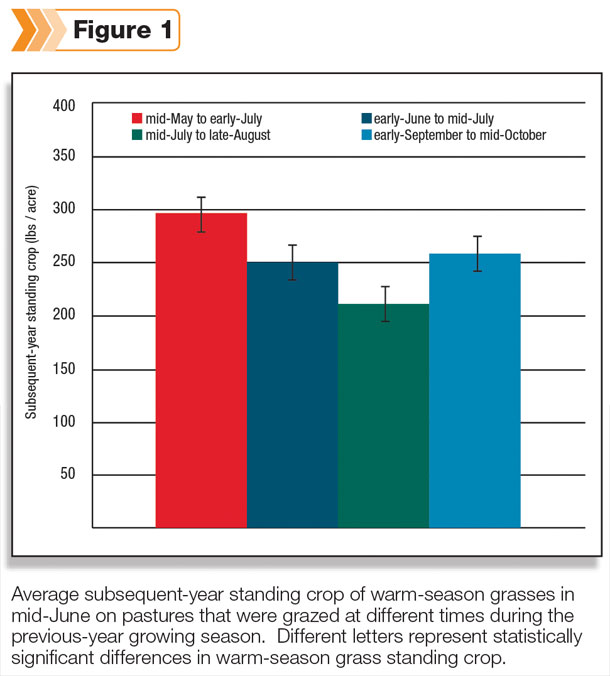

Recent research conducted in the Nebraska Sandhills evaluated the impact of grazing at different times during the growing season on subsequent-year standing crop of different plant functional groups.

Over a nine-year period, 40 to 45 cow-calf pairs and yearling spayed heifers were moderately stocked within a single herd, four-pasture deferred-rotation grazing method from May 15 to Oct. 15 each year (average pasture size = 100 acres).

This allowed for grazing on individual pastures during four different time periods during the growing season: mid-May to early June, early June to mid-July, mid-July to late August, and early September to mid-October.

Standing crop of cool- and warm-season grasses was collected in mid-June of the subsequent year to determine how timing of grazing in one year affected herbage production in the following year.

Standing crop of cool-season grasses at a pasture level were typically not influenced by timing of grazing during the growing season, but some evidence suggested grazing from early September to mid-October reduced subsequent-year standing crop on north-facing slopes and dune tops of Sandhills.

Subsequent-year standing crop of warm-season grasses was reduced when grazing occurred on pastures from mid-July to late August compared to grazing occurring early or later in the growing season (see Figure 1).

On average, pastures grazed from mid-July to late August produced 85 pounds per acre less warm-season grass forage in the subsequent year than pastures grazed from mid-May to early June, and 48 pounds per acre less than pasture grazed during early September to late October.

Understanding timing of grazing

In the mixed-grass prairie of the Sandhills, both cool- and warm-season grasses are important components of the forage resource.

Cool-season grasses typically begin growth early in the growing season and reach maturity in early to mid-June. Warm-season grasses begin growth and elongation as cool-season grasses reach maturity with higher summer temperatures.

The elongation period (late June through August) is when warm-season grass plants have used reserved carbohydrates stored in the roots and crowns of the plant to initiate growth and seed production.

Reserves are being replenished through photosynthesis at this time. However, if the leaf material is removed, there may be limited opportunities for that plant to fully replenish carbohydrate stores in the roots before dormancy.

As a result, root length and subsequent-year standing crop of warm-season grasses can be negatively affected when grazing occurs during this elongation period.

Cool-season grasses appear to be able to use available soil moisture for regrowth following moderate grazing early in the growing season (i.e., the time when cool-season grass species are in the elongation phase of growth) if allowed rest for the remainder of the growing season.

However, grazing on cool-season grasses in the early fall may have some negative effects on subsequent-year standing crop. This is likely the result of bimodal growth periods when adequate soil moisture and temperatures allow for cool-season grass regrowth in the early fall prior to winter dormancy.

Grazing on this regrowth may be harmful to the plant and should be avoided in multiple years.

Deferment from grazing at different times of the growing season in consecutive years improves warm- and cool-season grass vigor.

After nine years within a four-pasture deferred rotation when timing of grazing was rotated annually, frequency of desirable warm- and cool-season grasses increased on the study pastures in the Nebraska Sandhills.

Creating a management plan that rotates the timing of grazing on pastures will provide important benefits and reduce the risk of grazing at critical times on different plant functional groups on mixed-grass, upland ranges. ![]()