Over the last three-decade to four-decade period, the beef industry has witnessed marked changes in a number of economically important traits. Many of the changes that have occurred are due to improvements in phenotypic evaluation and reporting, and in the implementation and use of genetic selection tools such as expected progeny differences (EPDs).

EPDs represent the beef industry’s most powerful source of information for selection and genetic improvement. EPDs are the best estimate of an animal’s genetic worth.

Traditionally, since beef producers are paid for their animals on the basis of weight, or in some cases by the merit of animal carcasses, most EPDs reported in breed association sire summaries involve growth traits and carcass traits.

Today’s suite of EPDs beef producers have at their disposal include EPDs for growth traits, carcass traits, reproductive traits, maternal traits and index EPDs that combine a variety of traits for specific selection objectives.

Beef producers have excellent tools to use in making changes and improvements in a variety of traits. However, results from a recent beef industry survey suggest that EPDs may not be receiving the attention they deserve in selection programs.

In 2014, a survey was conducted to assess the awareness, attitudes and knowledge of commercial beef producers regarding a variety of feed efficiency and genetics concepts. The survey was completed by 467 beef cattle producers from across the U.S.

Survey respondents included commercial cow-calf producers (59.9 percent), stocker operators (13.3 percent), seedstock and commercial producers (12.0 percent), seedstock/purebred producers (11.5 percent) and feedlot operators (3.2 percent).

Making the most of data

Beef cattle producers have a great deal of information that can be used as a basis for selection decisions. However, all of that information is not created equal and does not provide the same level of evaluation of an animal’s genetic worth.

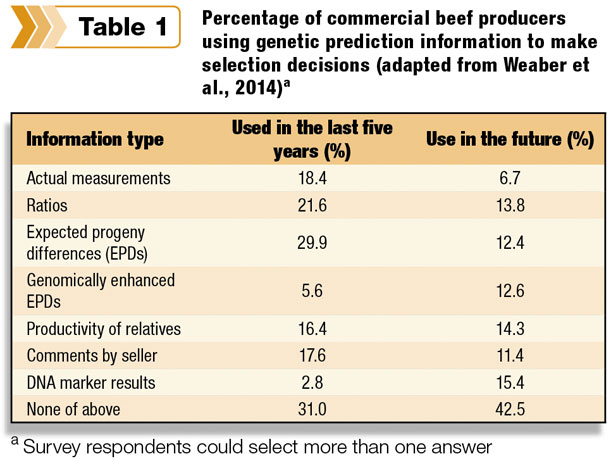

The 269 commercial cow-calf producers that participated in the survey were asked to identify the types of information they used for genetic prediction in the past five years, and what types of information they plan to use in the future (Table 1).

Clearly, beef producers are not always using the best source of genetic prediction information when making selection decisions. Only 30 percent of the survey respondents indicated they used EPDs for genetic prediction/selection decisions in the past five years.

Looking to the future, a very low 12 percent of producers indicated EPDs would be made part of their genetic prediction/selection decisions. Thirty-one percent of the survey respondents indicated they did not use any of the listed genetic prediction information in the past five years, and 42 percent indicated they would not use the information in the future.

Actual phenotypes, or performance measurements (weights, heights, centimeters, scores, etc.), are affected or controlled by several factors including management, environment and genetics.

Actual measurements are not very useful when trying to determine how good a parent an animal might be, since the animal’s actual performance for a trait is influenced by the management and environment to which the animal was subjected.

In other words, an animal may appear to be superior or inferior due to the environment in which the animal was raised and not because of the genetics the animal possesses and will pass on to progeny.

Good management and a good environment can mask poor genetics. Generally, actual performance measurements are not good indicators of an animal’s genetic worth.

Ratios can be an improvement over actual measurements. A ratio is an expression of an individual animal’s performance compared to the average of a group’s performance. To be fair and accurate, animals compared in a ratio should be in the same location, of the same sex, of similar age and managed alike.

Ratios are meant to compare animals within a group and not from one group to another. On the other hand, EPDs can be used to compare animals from one group (herd, location, etc.) to another as long as the groups are within a single breed.

Applying EPD tools

It is well-documented that EPDs are the single best tool for making selection decisions. EPDs are indicators of the genetic worth of an animal as a parent. They are computed using information on the individual animal and its relatives.

As mentioned previously, actual performance measurements (weights, heights, centimeters, scores, etc.) are affected or controlled by factors such as management, environment and genetics.

EPDs are adjusted (non-genetic factors removed or accounted for) to allow a fair comparison of animals born in different years, subjected to various management protocols and raised under different environments. They provide more accurate information for comparing the genetics of animals than actual performance measurements or ratios.

Another interesting piece of information from the aforementioned survey is who commercial producers consider as valuable sources of breeding and genetics information.

Survey respondents most frequently identified unpaid consultants [neighbors, friends, etc.] (39 percent) as a trusted source of information. The unpaid consultants were followed by veterinarians (30 percent), extension professionals (30 percent), seedstock producers (28 percent), Internet searches (18 percent), farm supply or feed store staff (18 percent), breed association personnel (15 percent), A.I. stud personnel (12 percent), popular press sources (9 percent) and paid consultants (2 percent).

EPDs represent the beef industry’s most powerful source of information for selection and genetic improvement. EPDs are the best estimate of an animal’s genetic worth. EPDs are calculated by breed associations and presented in the breed associations’ sire summaries and a variety of other venues.

Before implementing a selection protocol, producers should define their production goals, set minimum performance standards for each trait of interest, evaluate their herd and select animals to be parents that are superior for the traits of interest and that will allow production goals to be met.

There is no question that EPDs have provided the means for improvement and progress in many beef cattle herds. However, the results of this survey show there is room for improvement when it comes to the use of EPDs in making selection decisions. ![]()

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

- J. Benton Glaze Jr.

- Animal and Veterinary Science Department

- University of Idaho