In order to do this, we must recognize and treat sick animals (individual health) and have a “big picture” perspective on the collective health of the entire population (herd health). These – together with good nutrition and a clean environment – can help us achieve our goal.

There are two basic strategies that apply to all diseases: exclude and prevent the disease from entering the herd (biosecurity) or control and eliminate disease that is already present within a herd (biocontainment).

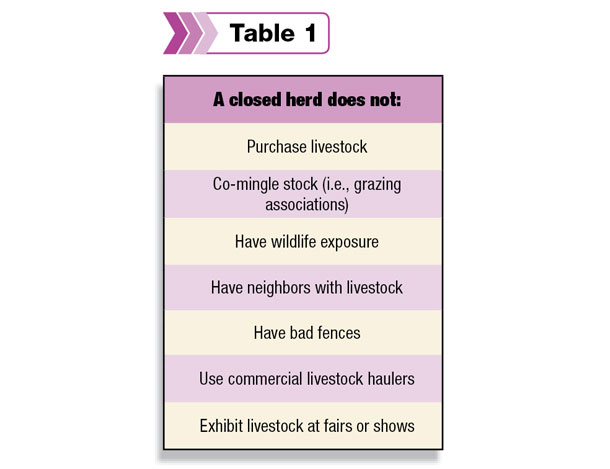

We talk about maintaining a “closed herd” as the ideal herd biosecurity model, in which the cattle are essentially isolated from any source of disease, as opposed to an “open herd” in which cattle are regularly exposed to potential threats. You may consider a herd to be closed if you do not purchase and introduce new livestock into the existing population, but there are other sources of disease of which to be aware.

Essentially, all cattle herds have some level of disease risk, but the key to optimizing your herd health plan is to minimize and control these risks as much as possible:

-

Know the source and health of new purchases – Purchase animals known to be free from certain diseases (i.e., Tritrichomonas foetus, BVD-PI animals, etc.) and vaccinated in a similar manner to your existing animals. Remember that sale yard purchases have already mixed with all other animals at that sale and may pose a higher risk of disease.

- Quarantine livestock before integrating into the herd – A period of two to four weeks is long enough for many diseases to show clinical signs and subsequently resolve, thereby reducing exposure to the herd. If you take livestock to shows or fairs, quarantine them before re-introducing them back to the group, if possible.

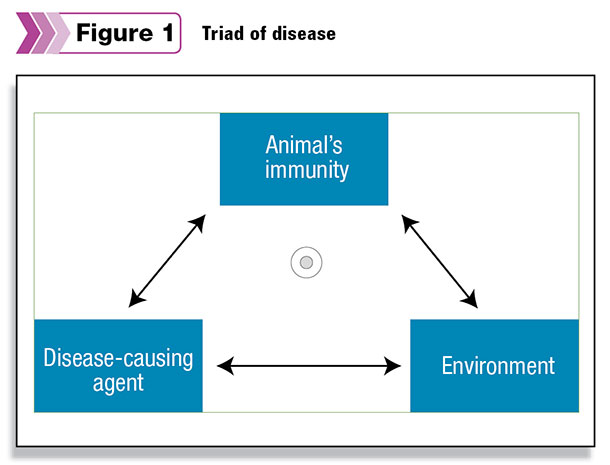

If a contagious disease is already present in your herd, whether it has been active for years or was just recently detected, biocontainment is your goal. There is a relationship between the individual animal’s immune system, the prevalence of the agent causing disease and the environment.

Improving any of these will help to reduce disease burden and improve overall health.

Improving any of these will help to reduce disease burden and improve overall health.

- Separate sick animals from healthy animals – This allows you to both appropriately treat and monitor sick animals and reduce further exposure to susceptible animals.

-

Implement appropriate vaccination strategies – This will help to strengthen individual immunity and, subsequently, herd immunity. With literally hundreds of commercial cattle vaccines on the market and varying production goals, there is no generic vaccination schedule that will work for everyone.

Your herd should be vaccinated against known diseases in your area that pose a risk (respiratory pathogens, reproductive pathogens, clostridial disease, etc.) on a regular basis (often annually). Develop a vaccination strategy tailored to your operation.

-

Alter the environment – By keeping the environment clean, dry and with an appropriate concentration of animals, you can reduce the incidence of certain diseases. Consider rotating pastures and even calving areas, especially if they become extremely wet, muddy and full of manure.

Intensive operations with large numbers of cattle in small areas have a higher chance of disease spreading quickly through the herd than do extensive, low-concentration operations.

-

Don’t forget your herd history – Use historical health data to help guide your disease protocols. If you have had mineral deficiencies in the past, for example, be sure to test animal levels on a regular basis.

If there are particular bacteria or viruses that have caused calf diarrhea in your herd, try to avoid carrying those over for the next calving season by cleaning up the calving pen and potentially incorporating a commercial scours vaccine into your health plan.

-

Surveillance – Monitor the herd for further signs of disease or deficiencies. If an animal dies, for whatever reason, a necropsy should be performed by your veterinarian or the local diagnostic lab. This can give you both information on why the animal died and any underlying problems that may be present in your herd.

Bacterial cultures, toxin screens and mineral/trace element levels are all valuable pieces of information you can use to benefit the overall health of the rest of the herd.

The easiest way to control disease in a population is to try to prevent its entry in the first place. Work with your veterinarian to develop individual animal treatment protocols and vaccination plans appropriate for your production goals.

If you have an unusually high number of sick or dead animals in a short period of time, you can work together on sample submissions and diagnostic tests that will lead you to a diagnosis and, hopefully, a starting point to control that disease in the future. ![]()

-

Bret McNabb

- Assistant Professor

- UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine Large Animal Clinic

- Email Bret McNabb