Thus, it is important producers know what their feed costs are and how they compare to benchmark values for other producers such that they can manage this important cost for long-term business profitability.

While the nutritional requirements of a beef cow are pretty well determined given her genetics, body size and the environment she is in, the specific feedstuffs used to meet those requirements can vary considerably.

Typically, spring-calving beef cows in Kansas are grazed on native grassland for about half of the year (e.g., May to October) and then rely on harvested feeds and crop residues for the remaining portion of the year.

However, it is possible to use native range along with supplements as needed for more months out of the year (e.g., year-round grazing).

In other words, there is a trade-off between the use of pasture and non-pasture costs in meeting the nutrient requirements of the cow and her calf.

Thus, a producer with higher-than-average pasture costs might still be competitive with other producers if non-pasture feed costs are lower than average. Likewise, a producer having high non-pasture feed costs might be cost-competitive if pasture costs are lower than average.

Analyzing multiple years of data

During the collection of the KFMA data, potential problems could arise within any year that might reflect more circumstance than management. For instance, in any year, perhaps producers in one part of the state received little or no summer rain, which might have resulted in lower weaning weights or higher feed costs.

To reduce the problem of random differences in costs across producers in a given year, a multi-year average was used for each producer. There were 79 operations that qualified with a minimum of three years of data.

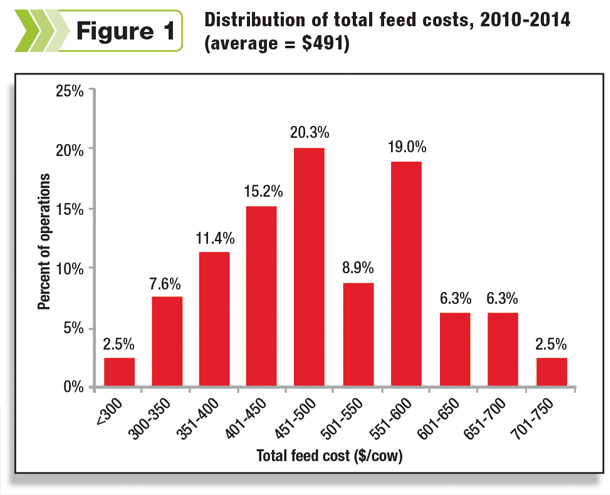

The data showed total feed costs averaged $491 per cow, but considerable variability existed as costs ranged from less than $209 per cow to $793 per cow.

The most common value (more than 20 percent of producers) was in the range of $451 to $500 per cow (Figure 1).

Across the same 79 producers, non-pasture costs had tremendous variability as the values ranged from $152 to $663 per cow with an average of $341 per cow. Pasture costs averaged $150 per cow but also had a large range from $43 to greater than $320 per cow for the multi-year average.

As might be expected, there is a strong, positive correlation between producers’ non-pasture feed costs and their total feed costs. This suggests having high non-pasture costs is indicative of having high total feed costs.

There is also a positive correlation between producers’ pasture costs and their total feed costs. However, the correlation is not particularly strong.

There is a significant and negative relationship between pasture costs and non-pasture feed costs. In other words, as the pasture costs increase (or decrease), the non-pasture feed costs decrease (or increase).

This suggests producers are possibly “trading off” between pasture and non-pasture feed. That is, it might be that producers with high pasture costs have low non-pasture feed costs and vice versa.

The grazing systems and strategies producers use (e.g., year-round grazing, early intensive grazing, rotational grazing, etc.) will impact their total costs, and this might help explain the relatively weak relationship between pasture and total feed costs.

There are other factors that might help explain differences between producers’ feed costs (both pasture and non-pasture). Cow size will impact feed costs, and thus an operation having smaller-than-average cows would be expected to have lower-than-average feed costs.

Likewise, producers with larger cows or creep-feeding calves will have higher total feed costs. Additionally, drought or other weather conditions might have significantly impacted individual producers’ costs and, more specifically, the relationship between pasture and non-pasture costs for their operation in a given year.

The data showed there is a fairly strong relationship between costs in 2014 compared to 2013. This suggests feed costs for individual producers tend to be fairly consistent (i.e., high-cost producers have high costs across years and low-cost producers have low costs across years).

This consistency reflects the management style and environment of an individual producer and should be evaluated more closely to determine whether it is a comparative advantage to be capitalized upon or whether it is a disadvantage that needs to be addressed.

When variability around year-to-year costs exist, it likely reflects less manageable factors (e.g., impact of drought, localized hay production, etc.).

Profitable vs. non-profitable

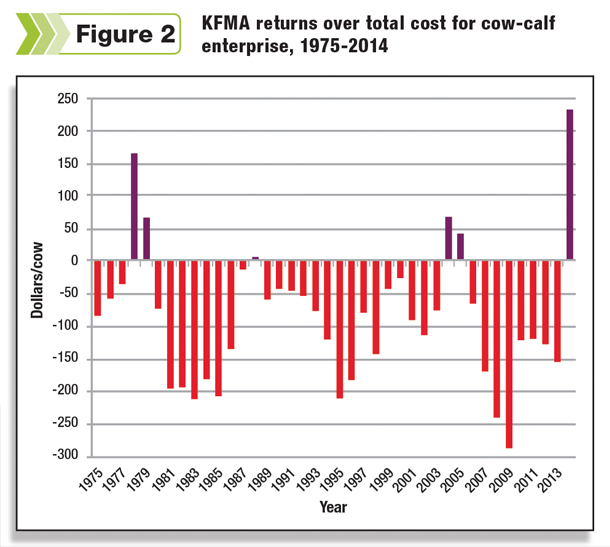

So what makes the difference in profitable versus non-profitable producers? KFMA analyzed returns over a 40-year period of 91 producers, on average (varying from 67 to 116).

Over the 40-year time frame, the average returns over total costs are -$85.72 per cow with a low of -$286.71 and a high of $233.35. (Returns over total costs were only positive six of the 40 years or 15 percent of the time; Figure 2).

At first glance, one might ask why anybody is in the cow-calf business if average returns over total costs are only positive 15 percent of the time. However, it is important to recognize that the unpaid labor and assets used in the operation reflect opportunity costs, and these can vary significantly between operations.

Table 1 reports average returns and costs for all 79 operations and for high-, mid- and low-profit farms.

High-profit operations generated about $133.51 (plus 16 percent) more revenue per cow than the low-profit operations.

When looking at the costs, high-profit farms had a $282-per-cow cost advantage over low-profit farms (24 percent advantage) and a $97 cost advantage over the mid-profit farms. High-profit operations had a cost advantage in every cost category compared to the mid- and low-profit operations, except for pasture.

Summary

Feed costs represent the single- largest cost for cow-calf producers and thus represent an important determinant of cow-calf profitability. More specifically, the difference in feed costs across producers is a major factor explaining profitability differences across producers.

Because feed costs are so important to profitability both in the short and long run, it is important that producers not only know what their costs are but also how they compare with other producers in the industry.

The feed cost structure of an operation reflects the management style and environment of an individual producer. Thus, it is imperative that producers recognize if this is a comparative disadvantage that needs to be addressed or if it is a comparative advantage that can be capitalized on.

Key points

- Keep records to know your numbers/costs.

- Know and understand your available grazing and feed resources.

- Know and understand the nutritional needs of your herd.

- Identify through evaluation and benchmarking areas to improve efficiency, sustainability and profitability of your operation.

Dustin Pendell is in ag economics at Kansas State University. Email Dustin Pendell.

Kevin Herbel is also in ag economics at Kansas State University. Email Kevin Herbel.

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.