Beef cow production in much of the western U.S. relies on forage from semiarid perennial grasslands. Efficient use of this resource is crucial to the sustainability of ranching operations.

However, cattle harvest efficiency, or the amount of available forage actually consumed by the animal, is often a relatively small part of the total forage produced. Sustainably increasing efficient use of the grass you have may be achieved by changing your grazing management.

Grazing management terms

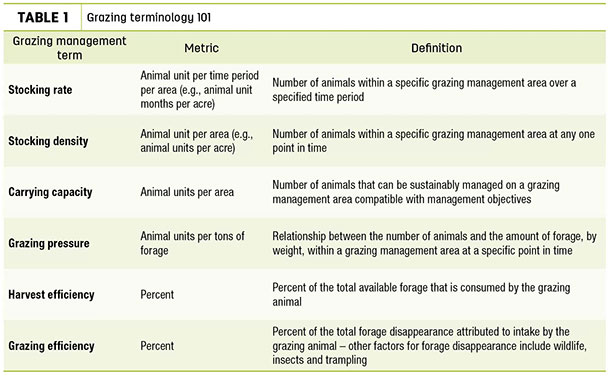

To fully understand the ways we can adjust grazing management to improve harvest efficiency, it is important to review the definitions of common grazing terms. These terms are closely related, but each term describes a different component of grazing management.

Understanding the carrying capacity, or the number of animals that can sustainably be grazed on a given rangeland, is the most important concept in grazing management. This number typically allows for variations in the annual stocking rate to meet the challenges in fluctuating precipitation amounts and the resulting amount of available forage.

Stocking density is often one of the factors that can be altered by increasing the number of paddocks in a rotational grazing strategy by focusing more cattle on a given area at any specific time. Grazing pressure increases as stocking density increases and as time within a pasture increases.

Harvest efficiency under different management scenarios

Under season-long, continuous grazing management strategies at moderate stocking rates (assume 50 percent use of the available forage), harvest efficiency for cattle grazing is typically estimated at about 25 percent of the available forage.

This means if you have 1,000 pounds of forage per acre, 500 pounds would be left as standing leaf and stem material for regrowth and sustainability of the plants, 250 pounds would be trampled or consumed by insects or wildlife, and grazing animals would consume 250 pounds.

This is a relatively inefficient system when compared to mechanical harvest with haying equipment, which may harvest over 90 percent of the available forage. However, the economics of allowing cattle to harvest their own feed for most of the year without the cost of haying is worthwhile and often the only logistically feasible way to harvest forage on a majority of the range and grasslands in the U.S.

While harvest efficiency in this continuously grazed scenario is low, diet quality selectivity is high. Because of the low density of competing animals and larger area, cattle can be highly selective in their forage diet. In fact, individual animal performance is often highest under this type of management scenario when compared to other grazing management strategies.

If the above pasture were to be divided into four separate pastures, and cattle were rotated in a deferred rotation during the growing season, the stocking density would be quadrupled on each of the four pastures at the same stocking rate. This is because the fencing of pastures would constrain the cattle to a smaller portion of the total area at any given time during the growing season.

As a result, grazing pressure is increased. Because cattle are constrained to a particular area and have more competition with other cattle to consume the best-quality forage diet, selectivity typically decreases, and cattle graze more uniformly across the pastures compared to a continuous grazing scenario.

Some estimates suggest increasing stocking density on pastures could improve harvest efficiency to 30 or 40 percent of the available forage.

In some regions, if adequate growing conditions persist after grazing occurs on early pastures, cattle can be grazed on plant regrowth during the late fall or winter at moderate levels after plants are dormant.

Winter grazing can further increase the number of grazing days and harvest efficiency on pastures without detrimentally affecting rangeland condition. This equates to more grass being effectively used by grazing animals and more flexibility in grazing management.

However, it is important to note that higher stocking-density strategies may not work in all situations and should be used with an objective-driven approach that includes considerations for work and logistic requirements, wildlife habitat and overall rangeland health.

In some cases, a lower harvest-efficiency strategy with appropriate stocking rates and fewer inputs of fence, water and labor may provide the most cost-effective management. However, if there are ways to increase stocking density, there may be potential to increase the amount of forage consumed by grazing livestock. ![]()

PHOTO: Grazing pressure increases as stocking density increases and as time within a pasture increases. Staff photo.

-

Mitchell B. Stephenson

- Range and Forage Management Specialist

- University of Nebraska – Lincoln

- Panhandle Research and Extension Center

- Email Mitchell B. Stephenson