The old saying “if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is” fits here.

A hydroponic system produces plant growth under artificial conditions in a greenhouse with a constant water system in operation. Some systems simply soak a tray of seed and let it sprout.

There is no soil or other medium. Usually, the systems also use artificial lighting to supplement natural light, and it is necessary to provide mineral nutrients in the water solution.

As an agronomist, I am amazed that I sometimes fail to convince a forage producer to apply fertilizer to his crop based on a good soil test when we can predict the yield response and a benefit that is more than the cost.

I commonly hear the excuse that it is just too expensive even though I can show a positive return on the dollar.

Yet some glossy pamphlet or website will get them all excited about some unproven product that claims to produce a lot of forage from very little.

Just put some barley or wheat seed on a tray and add water, and in about seven days you have a lush green fodder crop.

The problem is: You have actually reduced the net amount of usable energy in the feed. As the seed sprouts, the energy it needs to develop the cotyledon, roots and eventually the first leaves all comes from the seed.

Plant respiration is also using some of the seed energy to maintain cellular processes. Respiration breaks down the glucose and gives off carbon dioxide and water, which causes a loss of energy and mass.

Photosynthesis will gradually provide some energy in the form of glucose; however, a positive net photosynthesis is not attained until about 4 to 6 inches of leaf growth occurs.

Since the fodder system harvests the sprouts before the plant reaches a positive net photosynthesis, there is less energy in the seedlings than if you were to feed the seed.

The commercial systems I have seen advertised are rack systems with low potential for positive net photosynthesis, so a net energy loss would be significant.

I have used a hydroponic system to do research. It was a lot of work, and even minor problems can cause a catastrophic crop failure.

I didn’t calculate the expense of producing the forage because my interest was in controlling mineral nutrient concentrations, but the cost had to be several times what it cost to produce the same forage in soil.

The forage plants we grow have evolved over millennia and are robustly adapted to our environment. It would be difficult for humans to engineer a more efficient system when all things are considered, and for a long time period.

Some argue that hydroponic production is more water use-efficient than conventional agricultural systems.

However, since there is a net loss of energy and dry matter (DM) or mass from the system until at least 10 days, that argument falls flat because water use efficiency is calculated by the mass of forage produced divided by the mass of water used.

So even in a drought, the hydroponic system is not practical for producing forage.

What does the scientific literature tell us? A study at the Sandia Laboratory shows DM losses during sprouting in the 36 percent range. In other words, the process uses 100 pounds DM and produces 64 pounds DM as forage.

A recent study in Iran indicated that it is merely a transformation from a seed to forage with a net loss in mass. Regardless of how palatable the forage is, it doesn’t justify the cost.

Colleagues in land-grant universities from California to Wisconsin have made similar conclusions. A study at the University of California – Davis showed that sprouting resulted in a 24 percent DM loss in six days’ growth and more than 30 percent DM loss after seven days’ growth (click here to see Hydroponic Forage Production).

What about the high forage quality? The amount of crude protein stays about the same in the sprouts as in the grain, and although the concentration may be a little higher in the sprouts, it is because of the loss of total DM.

Would you buy hay from a guy who added 9 tons of water to 1 ton of hay and told you that you were getting a real bargain because he is only charging $40 per ton?

That is about the same ratio used when promoters advertise a 40 to 60 percent saving in feed costs because they are making the comparison on a fresh-weight basis – which is not appropriate. All feeds should be compared on a DM basis.

Websites claim that 10 pounds of seed will produce 50 to 60 pounds of forage. So 10 pounds of seed at 90 percent DM produce 50 pounds fresh forage at 10 percent DM.

Their own literature shows no gain in DM because 50 pounds x 0.10 = 5 pounds DM. Using their optimistic numbers, 60 pounds of forage produced and 0.15 DM leaves only 9 pounds of DM.

So producing 1 ton of barley sprout seedlings would take 333 pounds of barley seed. This seed would cost about $33.33 (330 pounds x $10 per 100-pound bag) at bulk prices, not certified seed.

Let us assume that labor and facilities would cost about $12 per ton – hand labor to roll up 1 ton of seedlings could easily take one hour. That puts the cost of barley seedlings at $50 per ton ($33 for seed plus $12 for labor and facilities).

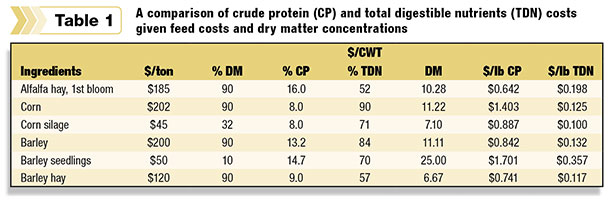

I used the University of Georgia’s UGA Feed Cost Analyzer spreadsheet to calculate the cost per unit of crude protein (CP) and total digestible nutrients (TDN) for barley seed and barley sprouts (Table 1).

Barley grain (seed) at $200 per ton costs $0.84 per pound CP and $0.13 per pound TDN. Given those assumptions, sprouted barley seedlings would cost $1.70 per pound CP and $0.36 per pound TDN.

So barley seedlings would cost twice as much per pound CP and three times as much for TDN as barley grain. Alfalfa hay, corn, corn silage and barley hay are all less-expensive sources of CP and TDN.

Conclusions

The hydroponic systems are a major capital investment in facilities, and the labor requirements are very high. There is a net loss of energy and mass with this system during the seven days.

That results in a product that is very expensive to feed. I recommend that producers search for science-based studies from land-grant universities to verify product claims. ![]()

Glenn Shewmaker is an extension forage specialist with the University of Idaho.

References omitted due to space but available upon request. Click here to email an editor.