Nitrates only become a problem if they’re not used by the plant and accumulate during adverse growing conditions like drought or freezing. Some plants accumulate nitrates more readily than others.

“The most common forages with nitrate problems are small-grain hays like oats, barley, wheat,” she says. “Corn can accumulate nitrates, and so do weeds like kochia, pigweed, lambs-quarters. Weeds are a concern because they may be the only thing that’s green during a dry summer or fall, and cattle readily eat them.

“Oats are generally the grand champion of nitrate accumulation, followed by other cereal hays, but we’ve also seen some surprises. It’s always best to check rather than just assuming.”

Plants in the sorghum-sudangrass family can also accumulate nitrates. Some annual crops are grazed rather than harvested. Test those crops before you graze them to assess risk. “Producers are more accustomed to testing something in a bale rather than on the stalk, but they need to be aware of these risks, too.”

Julie Walker, a beef specialist with South Dakota State University, says corn can have high nitrate levels under certain conditions like drought, but when made into silage, those levels decrease. “Research at Purdue University showed we can decrease nitrate levels with an ensiling process,” she explains.

“But if we cut forage for hay, such as a sudan, sorghum or millet in a drought situation, and it has high nitrates, baling does not decrease those levels. Harvested hay holds the level it was when cut, whereas ensiling feed will decrease nitrate concentration through the fermentation process.

“Always test silage, however, because it still may be high. It might have been extremely high when put into the silage pit. Even if it’s only half that level by the time you feed it, silage may need to be diluted with other feed to be safe.”

When nitrates climb

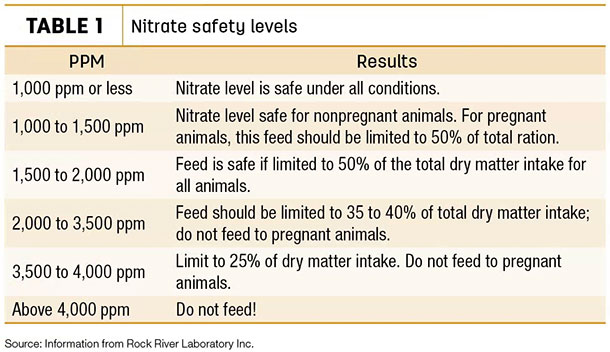

Endecott always recommends testing harvested forages to know the nitrate levels. “If we find levels high enough to be of concern, we can mix that forage with some other feed that isn’t high in nitrates to dilute it down to a safe level,” she says.

“Nitrate levels tend to decrease as the plant matures, so hay would be more apt to cause problems than straw, but I wouldn’t completely rule it out. I’ve seen straw samples that were high,” she explains. Some producers feed cereal hay or straw because it’s cheaper and mix it with a higher-protein feed or use protein supplement to balance the diet.

Some of the feeds that tend to be safe (and could be mixed with high-nitrate feeds to dilute them) include some of the grass hays or alfalfa.

“Every plant can have nitrates, but the level may depend on the amount of fertilizer applied,” says Walker. “If a farmer was growing corn, expecting 160-bushel corn, and fertilized the field to enable the crop to do that, and then the corn couldn’t grow that well, those drought-stressed plants were unable to utilize that much nitrogen.

“The nitrogen was readily available, and the plants started taking up nitrogen but then were stressed and unable to metabolize the nitrate and change it into protein (in the grain if it was a grain crop, or ears of corn in a corn plant). The nitrogen is still tied up in the plant, so it has a high concentration when harvested,” she explains.

When the animal eats a plant, nitrate is changed to nitrite in the rumen. “The nitrite is then converted to ammonia, which is then incorporated into amino acids and protein. A high level of nitrate gets converted into nitrite – which is not converted quickly enough into ammonia. This is when cattle develop nitrate poisoning,” she says.

To avoid problems, some of these forages can be made into silage rather than hay or diluted. “To feed a high-nitrate forage, we can mix it with lower-nitrate feeds like grains or legumes, or a grass hay put up before it got into a drought situation. If forage is questionable, we can do a gradual increase, adding it into the diet slowly instead of all at once, so the rumen microbes can adapt to it,” Walker says.

Make sure the diet is balanced. “This enables the animal to utilize forage better and have the rumen as functional as possible so it can convert the nitrites more readily into ammonia and decrease the probability of toxicity,” says Walker.

Regional forage check-ups

In areas that experienced drought this past summer, check forages. “Some people in eastern Montana are cutting wheat for hay because it didn’t grow enough to harvest for grain,” Endecott says. They should test that hay, especially if the field was fertilized. The amount of nitrogen fertilizer applied – with expectation for a grain crop – might result in excess levels in plants unable to reach full maturity.

If the forage containing nitrates is what’s available, you need to mix it with other feeds. “Run a nitrate test on feeds you want to mix with, even if you don’t expect those to be toxic. All plants contain some nitrates because they utilize it as part of their metabolism. There will be some level of nitrate in all forages.”

You can fine-tune a mix based on milligrams of nitrate per pound of animal bodyweight – if you have a good handle on all nitrate sources – to make sure the combination of sources won’t add up to toxic levels. “If nitrate levels in the drinking water are high, this can be another concern. The multiple sources could be toxic when added together,” says Endecott.

“We just did a drought management workshop tour in northeastern Montana and recommended testing to fine-tune feed management. People may have to accept a little higher risk just because they don’t have other forage available.”

Many labs send back test results with a chart listing levels safe or unsafe and feeding recommendations. “Here at SDSU, we have a publication that includes a table with those amounts and how much can be included in the ration,” Walker says.

In most cases, high-nitrate feeds can be utilized when diluted, ensiled or fed to lower-risk animals. With some levels, it’s safe to feed to younger animals rather than to pregnant cows. Your local extension office can answer questions or help put together a strategy for utilizing various forages.

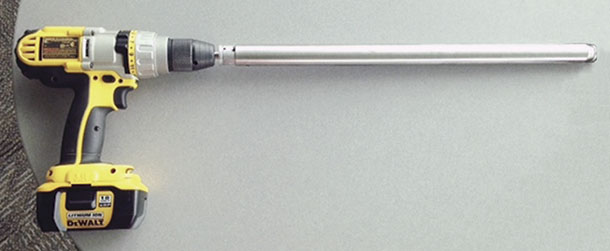

“Here in Montana, most of our offices have a hay probe and drill they loan out – for taking samples,” says Endecott. Extension offices also have relationships with various labs and can help you send in samples for testing. ![]()

PHOTO 1: A nitrate quick-test kit. Photo provided by Shannon Williams.

PHOTO 2: A sampling probe attached to a drill.

PHOTO 3: Danielle Staudenmeyer, a Montana State University animal and range sciences grad student, takes a sample from a big round bale. Photos by Emily Grunk.