Based on the most recent Texas A&M AgriLife Standardized Performance Analysis (SPA) database, it costs the average Texas producer $796 to keep a mature cow around for a year. Of course, not everyone is “average.” The lowest-cost-quartile producers only spent $618 per cow per year, while the highest-quartile producers spent $1,261 per cow per year.

If you break down where those costs occur, most people would probably correctly guess feed and labor are among the biggest components. But it surprises many people depreciation is actually slightly larger. Collectively, depreciation, feed and labor account for 46 percent of the total annual cow cost for most producers.

The benefits

Controlled calving seasons have a number of benefits that include improved herd fertility, heavier weaning weights and more uniform calf crops. Uniformity may offer more marketing options and, when age variability is minimized, replacement heifers can be better managed to reach a timely puberty for that critical first breeding. Also, herd health programs are easier to implement and monitor in herds with a defined breeding season.

For example, programs to control calf scours, pneumonia and other calfhood diseases are easier to implement in similar age groups of cattle. Sexually transmitted diseases such as vibrio or trichomoniasis can be recognized and dealt with before they become chronic in the herd. Timely testing for reproductive diseases such as BVD are easier to manage in a herd with a controlled breeding season.

Most vaccines, and especially those for reproductive diseases, require they be administered at specific ages or at a specific time in relation to when breeding is expected to begin, and a defined calving season allows more options such as strategic use of modified live/killed vaccines. Managing herd nutrition is another area that should be considered: When cattle are supplemented, the whole herd gets fed. It is impossible to accurately deliver supplement to dry cows and lactating cows when they are together in the same pasture. Nutrient requirements are most affected by lactation, and especially peak lactation, which occurs about two months after calving.

The challenges

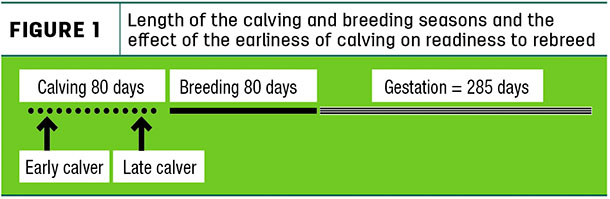

There are only 365 days in a year. One of the biggest challenges to managers trying to keep cows on a 12-month calving interval is the fact a cow or heifer is pregnant for about 285 days of the year. That only leaves 80 days for physiological processes such as calving, uterine repair (involution), resumption of the estrous cycle and ultimately re-breeding to occur so the cow “has a calf every year.”

“Postpartum anestrus” is another challenge. Delivering a calf is stressful, both anatomically and physiologically. So cows and heifers do not have estrous cycles for a period of time post-calving. For most cows, this anestrous period lasts a minimum of 45 days. It will be longer (often much longer) if cows are in poor body condition at calving or if they have experienced calving difficulty. As Figure 1 depicts, cows that calve early will have more time to recover from calving before breeding begins versus cows that calve late.

And, as Figure 1 also depicts, if managers want to keep their cows calving on a true 12-month calving interval, the longest a calving/breeding season can be is three months. Some managers use even shorter 60- or even 45-day seasons effectively.

Dealing with bulls

Removing bulls from the cow herd following the breeding season is the most common method of managing the breeding season and thus controlling the calving season. However, some producers simply don’t have a place to put herd bulls. This is especially true for smaller herds with limited land area or smaller herds where there may only be one or two herd bulls servicing a small number of cows. Some bulls don’t stay where they are put, often tearing up fencing and other infrastructure in the process. This may again be true for smaller herds where a bull just gets lonesome and wants to be with other cattle.

The good news is: It is possible to leave bulls with the cows year-round and still maintain a calving season of three months or less. It just requires two main things: access to someone who is skilled in either palpation or ultrasound to determine fetal age, or the use of calving records, and the “self-discipline” to cull pregnant females from the breeding herd.

To look a little bit closer at the process, first determine the time of year you want to calve and breed. For most producers, that breeding season of three months or less should probably match the time of year when pasture forage quality is the best – and most cows in herds that calve over extended periods will tend to naturally breed at that time of year anyway. It is probably easiest to do pregnancy diagnosis just prior to those months you have targeted for the calving season. An exact strategy will depend somewhat on the proportion of the herd calving outside the desired period.

But, for example, a rancher in central Texas wants to breed cows with the best-quality spring forage in the months of March, April and May to produce December, January and February calves. Pregnancy diagnosis could be performed in November. Heavy-bred cows diagnosed in their third trimester would be kept for the breeding herd. Cows identified as open or short-bred can either be sold as open cows, or bred cows, or calved out and sold as pairs later – or even kept and bred and managed in a separate herd which is then allowed attrition.

Another option is to use calving records from the previous year in place of pregnancy diagnosis, to similarly identify the females that either fit or don’t fit the desired calving period. This procedure is no doubt easier to do in smaller herds, or at least in smaller pastures, where cattle are easily and frequently observed.

Remember, if bulls are with the cows year-round, there is a chance heifer calves may get bred to bulls that may not be calving-ease sires. So be sure to wean heifer calves before 8 months old or so. Also, when bulls are with the cows year-round, there is a higher chance of breeding daughters. This may not be the most ideal genetic situation. But for some producers, it may be something they just decide they will tolerate. Some managers who do keep bull daughters will change bulls every three years or so.

Others may decide to just sell all heifer calves. Replacement females are then purchased as either open cows or bred cows that will calve during the desired period. Realize there are inherent risks to purchasing outside cows if the health and vaccination status is not known. And even then, diseases such as BVD, vibrio or trichomoniasis can be brought into the herd. It is probably a higher risk with the purchase of open cows, but even bred cows can be carriers, and diagnostic tests are problematic for cows. The safest strategy would be to buy replacement cows from well-managed herds and monitor with appropriate diagnostic testing.

Calving seasons should be managed to make sure cows calve every year and are paying their way. Methods to accomplish a 12-month calving interval may include culling from pregnancy diagnosis, either with or without bull removal, or culling from calving records. ![]()

Thomas Hairgrove, DVM, is an associate professor and extension specialist with Texas A&M AgriLife Extension.

PHOTO: For those that don’t have a place to put bulls, a calving season of three months or less can still be maintained – as long as the age of the fetus is determined and any cows are culled that didn’t make the breeding window. Photo by David Cooper.

-

Bruce B. Carpenter

- Professor and Extension Specialist

- Texas A&M AgriLife Extension

- Email Bruce B. Carpenter