The COVID-19 virus has disrupted our lives and businesses, including the beef industry. When beef processing plants had limited production because employees became quite ill due to the contagious and rapid spread of this virus, supermarket meat cases were empty. Consumers turned to buying locally raised beef, and one niche market that has gained a lot of traction is the grass-fed beef segment. Many wanted to support local ranchers, while others enjoyed the convenience of online ordering. Health-conscious customers were interested in the increased amino acids found in grass-based beef. They all wanted a reliable source of beef cuts.

Carrie Balkcom, executive director of the American Grass-fed Association (AGA) says, “We are always distressed when any part of the beef industry is impacted as dramatically as ours has been, for the folks who sell into these markets and for the workers impacted by it.”

Most consumers are at least four generations removed from understanding how their food is produced. Balkcom says the media has made shoppers more aware of how grocery stores receive products for the meat counter. This information has also helped AGA producers experience a substantial uptick in grass-based beef demand.

“Our producers who are capable and nimble enough to transition to online sales have seen a huge increase,” Balkcom reports. “Some of our larger producers have seen online sales increase 500 to 1,200 percent. Smaller producers, reliant on restaurants, lost sales immediately. Operators capable of selling online stepped up to the plate, offering to take their animals because they had a market for them.”

With the current high demand, grass-fed beef producers cannot always meet their customers’ requests because small processing plants are also busy. Although a few producers have on-farm abattoirs, for the last 20 years, most operators have conducted business with small processing plants. Many of these handle beef and other livestock, but some also process deer and other seasonal wild game.

Processors want to increase production but are taking a hit from paying overtime to the USDA meat inspectors who examine items shipped across state lines. Overtime may run $100 per hour. That’s $800 a day or even $1,500 if a company wants to run two extra shifts. This is expensive for a small processor. Balkcom reports that U.S. Sens. Jerry Moran (R-Kansas) and Michael Bennet (D-Colorado) have introduced the Small Packer Overtime and Holiday Free Relief COVID-19 Act to reduce fees for small meat processors.

Balkcom advises consumers interested in locating grass-fed products to check the AGA website at American Grassfed for local producers. It also lists guidelines for beef operators. AGA is the sole grass-fed organization that only certifies American-born and -raised animals.

“Right now, keep doing what you’re doing and do it well,” Balkcom advises grass-fed beef producers. “You don’t have to scale up to stay in the market. If you need assistance, such as how to get your product to market, or if your market was selling to auctions, which dried up, reach out to us and we’ll try to help you. Other folks are looking for cattle to put into their supply chain. We have webinars to help you understand the rules and regulations you have to follow.”

Opportunities for grass-fed

John Ikerd, Ph.D., is an agricultural economist, teaches sustainable economics and has written six books on sustainable agriculture and sustainable economics. He says the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the conventional beef system, slashing the amount of beef flowing through the market, particularly to supermarkets.

Grocery stores also had to compete with institutional markets or restaurants for supplies. Low beef inventory forced people to find alternative beef sources because grocery stores could not stock their meat cases or prices had increased dramatically. Ikerd says in one situation, prices jumped 10% in one month.

Consumers looked to grass-based or alternative beef producers, whether cattle were grass-fed or had some grain feeding on the end of production. Many grass-fed beef producers had a head start by selling to established customers with online sales and farmers’ markets. They were happy to sell their products to new customers.

“The COVID-19 virus pandemic gives the grass-based and alternative producers an opportunity to access and keep customers they would not have had otherwise,” Ikerd reveals. “That’s a big impact.”

Ikerd advises grass-fed operators to use this opportunity to prove their product’s quality and to help new customers understand the difference between grass-based beef and the conventional meat they are accustomed to buying in the grocery store.

Grass-fed producers can share different preparation methods and explain what consumers may expect regarding fat and marbling. Cooking tips and recipes are available on the AGA website. He says it is critical that as producers gain new clientele, they continue to educate them so they do not return to the supermarket when supplies are plentiful.

“The grass-based beef and alternative markets focused on individual cuts,” Ikerd explains. “The price tends to be high for those pieces. When producers are selling a 50-dollar or 75-dollar bundle, they may also mix lower-cost cuts with the higher-priced cuts. The average bundle price may be more in line with what consumers were paying at the grocery store before [the COVID-19 virus].”

This strategy would allow producers to continue to cater to the high-end customers who understand the value of expensive cuts but expand the customer base by offering a package or bundle that enables the customer to look at a per-pound price.

Producer perspective

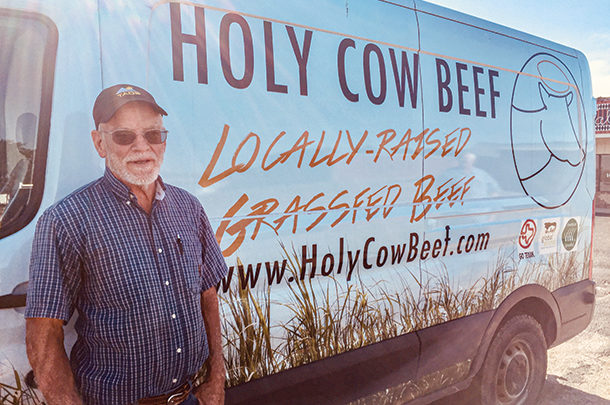

Weldon Warren and his wife, Ann, raise and finish grass-fed cattle for their customers in north Texas, serving the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, and in West Texas, serving Lubbock, Amarillo and Midland for their company, Holy Cow Beef. His Angus operation allows him to produce quality pasture-raised and pasture-finished dry and wet-aged beef. He provides grass-fed beef cuts to four Lubbock stores and one Midland store as well as customers who want larger quantities, ordering beef by the quarter or half.

Grass-fed cattle graze on Weldon Warren’s ranch southwest of Lubbock, Texas. Photo provided by Weldon Warren.

Grass-fed cattle graze on Weldon Warren’s ranch southwest of Lubbock, Texas. Photo provided by Weldon Warren.Since he sells only in Texas, the Texas Department of State Health Services’ inspectors check his beef products. Like many other grass-based operators, his business has increased dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic; he could not meet the increased late winter and spring demand until June because his local processor was also swamped with additional demand.

Warren’s cattle have at least a 50% Red or Black Angus influence. He says, “All the expected progeny differences (EPD) data the Angus Association compiled early in its history gave ranchers a significant leg up moving into the future. A beef operator would know the long-term benefits of buying an Angus bull. These cattle are docile and have increased intramuscular marbling for a nice eating experience, and their fatty acid profile is healthy and desired by my customers.

“Grass-fed producers should communicate, reach out and touch their community through social media and community networking, word of mouth and farmers’ markets to build a customer base,” Warren concludes. “If customers like the flavor profile of those products, then that business will grow over time.”

Grass-based and other beef producers have demonstrated great ingenuity, creative marketing and integrity during a difficult time as they provide quality products during an unexpected crisis. Their goal is to offer a safe supply of tasty, healthy beef for their established and new customers.