In the day-to-day churn of our dairy farms, it’s easy to lose sight of things that can have a direct impact on our efficiency and profits.

Feed mixing errors can result in higher costs, lower profits and, potentially, sick cows. Worst of all, these errors aren’t obvious unless you have a feed management system and are using it consistently. Your farm could be leaking profits and you might not even know it. If you don’t have a feed management system, or you aren’t using the one you have properly, you’re blind to mixing errors and other problems.

Finding and fixing these errors depends on using your farm’s software to its full potential. Feed management and herd management software systems help you gather data, but it’s up to you to dig a little deeper to understand what it means.

Let’s look at a hypothetical problem. You see a drop in percent butterfat on a recent processor email and decide to take a closer look.

Of course, when troubleshooting a problem like this, be sure to look for the most common issues:

- Did forages change?

- Are dry matter percentages correct?

In addition to these questions, don’t forget to consider the possibility of mixing errors.

What are mixing errors and how should I track them?

Mixing errors are simply how many pounds of each ingredient actually went into the mixer (actual weight) minus how many pounds should have gone in (call weight). To track mixing errors, you need feed management software. Without software, you can take steps to limit errors, but you cannot track them.

Feed management systems do a great job of recording call weight and actual weight, but be careful with average load or day errors.

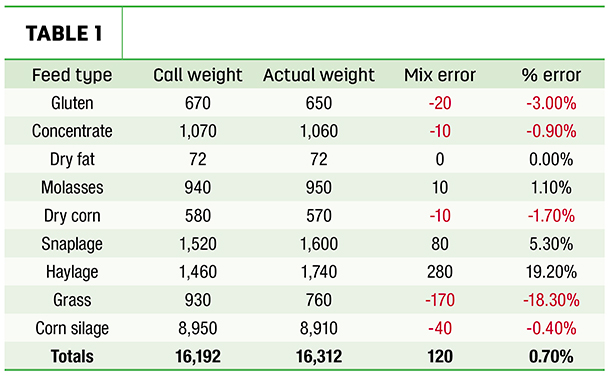

Consider the example in Table 1.

The total mix error is the sum of mix error, 120 pounds. The 0.7 error percentage is computed by dividing the mix error (120) by the call weight (16,192). At first glance, this percentage looks acceptable, but a closer look reveals errors in haylage (280 pounds over) and grass (170 pounds under). On average, the mixing error is small, but in reality big mistakes were made on at least two of the ingredients.

To understand mixing errors, stay away from averaging loads and concentrate on actual ingredients.

What is an acceptable mix error?

There are some commonly held rules of thumb around mixing errors that should be debunked. I still hear plus or minus 3% as a goal for mixing errors. Let’s think about mixing errors in a different way.

Fermentation in a cow’s rumen has many similarities to fermenting beer. If you happen to drink Bud Light, you know that Bud Light in Florida tastes the same as Bud Light in Michigan. Do you think this would be true if the brewmaster could be within 3% for each ingredient? It’s very doubtful. In our example, using corn silage, a 3% error would be approximately 269 pounds, which seems excessive.

My goal has been for 80 percent of “dumps” to be within plus or minus 30 pounds of call weight. Admittedly, this does not account for the magnitude of the mix error, but it provides an attainable goal.

Do mixing errors really matter?

Yes, they do matter. The better question is, “How small do mixing errors need to be before they don’t matter?” I look at mixing errors as a control point. They are easy to monitor and, if kept in control, we tend to see fewer one-off digestive issues and more consistent component yield.

How can mixing errors be improved?

To start, keep an eye on mixing errors and share the information with your feeders. Feedback does wonders.

Pick a number, such as 30 pounds, as a “good enough” goal. Most errors are overages caused by trying to hit zero, then bouncing over. If plus-or-minus 30 pounds from the call weight is acceptable, try coaching your feeders to advance to the next ingredient when they get within 30 pounds of the call weight.

Consider using a base mix combined with smaller adds, such as gluten, dry fat, molasses and dry corn. Talk to your nutritionist about specific options that might work best for your situation.

Kelly Bean, along with his son Keegan, founded Dairy Margin Tracker in 2014. Born and reared on an upper Midwest dairy farm, Bean is a dairy nutritionist and former dairy farm manager. Their company offers a suite of web-based dairy farm management tools that automatically gather data from both feed and herd management systems and makes this data available via smartphone to interpret results and make changes.