2022 was a challenging year regarding precipitation throughout much of the Central and western portions of the U.S. As we write this in April 2023, many major cow-calf production regions, particularly in the central and southern Plains, are continuing to experience drought. In the absence of sufficient precipitation, pastures and rangelands that were stressed last year will likely have delayed and/or reduced production again this year.

This will impact decision-making including “rule of thumb” guides, which are often implemented to simplify such decisions. The rules of thumb, or short phrases, discussed in this article originated from ways in which we have observed land managers try to make straightforward pasture management decisions. Some of these rules have merit and scientific or economic data to support them; however, some seem unfounded and lack informational support.

A complete list of 12 rules of thumb was originally included in a series of Kansas State University Beef Tips articles (“Evaluating Rules of Thumb for Grazing Management,” Parts 1, 2 and 3). However, our objective is to review some of these rules most impacted by drought and specifically address how they may be adjusted when pastures are stressed. Some rules from the original list are less impacted by drought, thus are not included. A “thumbs-up” means it’s a rule of thumb with merit, and a “thumbs-down” indicates the rule of thumb lacks scientific support.

Take half and leave half

This is probably the most common and important rule of thumb for rangeland managers. Finding this forage balance is especially important during and following drought, as forage production will most certainly be less than expected for the original season stocking rate. Often, overuse of forage during the year of drought or forage going dormant during the growing season can reduce the amount of green leaf material present at the end of the growing season to produce plant sugars needed for storage, winter survival and spring greenup the following season. Data from the Kansas State University Ag Research Center in Hays, Kansas, suggests forage production in the year following a drought is on average 10% to 15% below the percentage of average precipitation the year following a drought. So, for example, if precipitation is 110% of average the year following a drought, forage production has been 95% to 100% of average. Following a drought year, stocking rates can reasonably be adjusted downward prior to the next growing season based on the previous year’s growing conditions.

If it’s not grass, it’s a weed

Animal consumption and preference data do not support this rule of thumb. During or following droughts, some forbs may become more visible or prominent because of reduced grass growth or density. These forbs are often capitalizing on available water from different depths in the soil profile than grasses because of their differing root structures. These forbs can be more important to animals during drought, as they may be some of the main plants continuing to grow and stay green. Some less desirable forbs that grazing animals avoid could also become more abundant following drought. Many of these will be visible for one or two growing seasons until grasses reassert their vigor and dominance. In these cases, forbs just capitalize on this growth cycle based on weather patterns, and then become almost absent without any specific management to target their control. Any efforts to control weeds during or following drought should be done based on the species involved, the level of abundance and the potential for long-term presence and suppression of other desirable forages in the stand rather than a general blanket control application.

What you see aboveground is what you get below ground

This rule of thumb stands out during drought. Grasses with abundant aboveground biomass will also have an abundant root system. More than half of a grass plant's total biomass is in the root system. Grasses with more leaf material and aboveground biomass going into drought (less defoliation) will also have more total roots for exploring soil volume to gather moisture and will have more carbohydrate reserves for surviving the drought. Grasses from heavily utilized pastures declined in cover more quickly than grasses from light- or moderate-use pastures during the extended drought years of the 1930s.

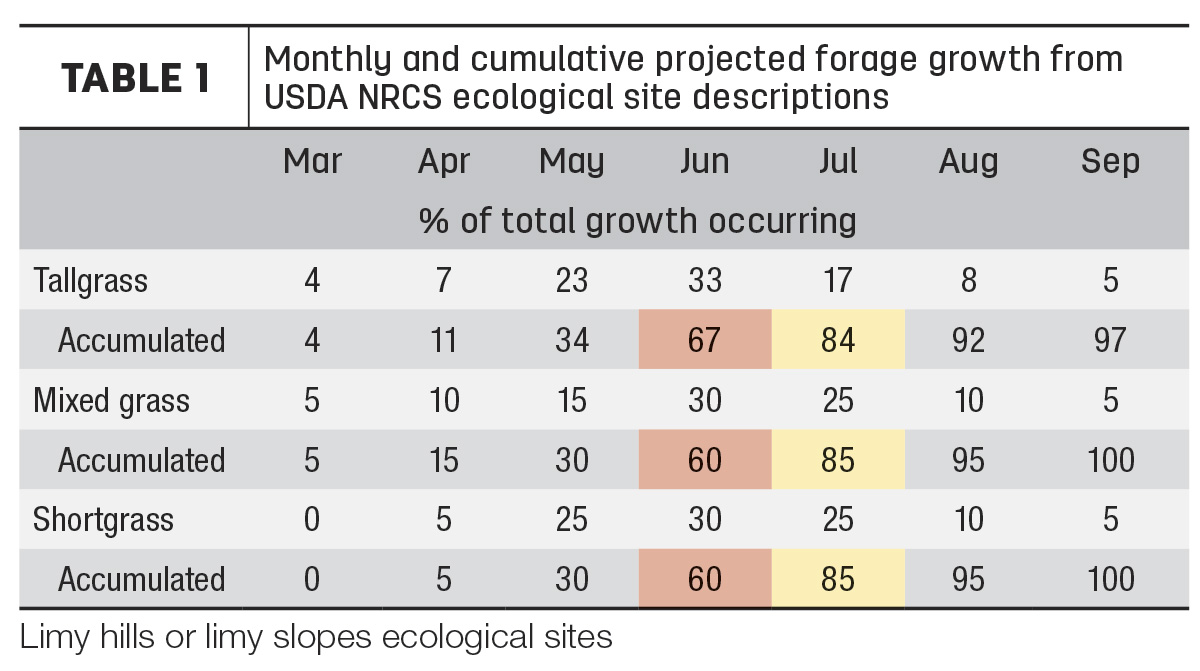

Sixty percent of pasture growth occurs by July 1

Rangelands across Kansas are dominated by native warm-season grasses, and typically have 60% of their biomass produced by the end of June (see Table 1). With an early-season drought, these percentages may be somewhat altered. Early-season drought followed by late-season rains may result in a greater proportion of the year’s growth occurring later in the season, but the total overall yield for the year probably will be much reduced.

Wet winters produce more grass

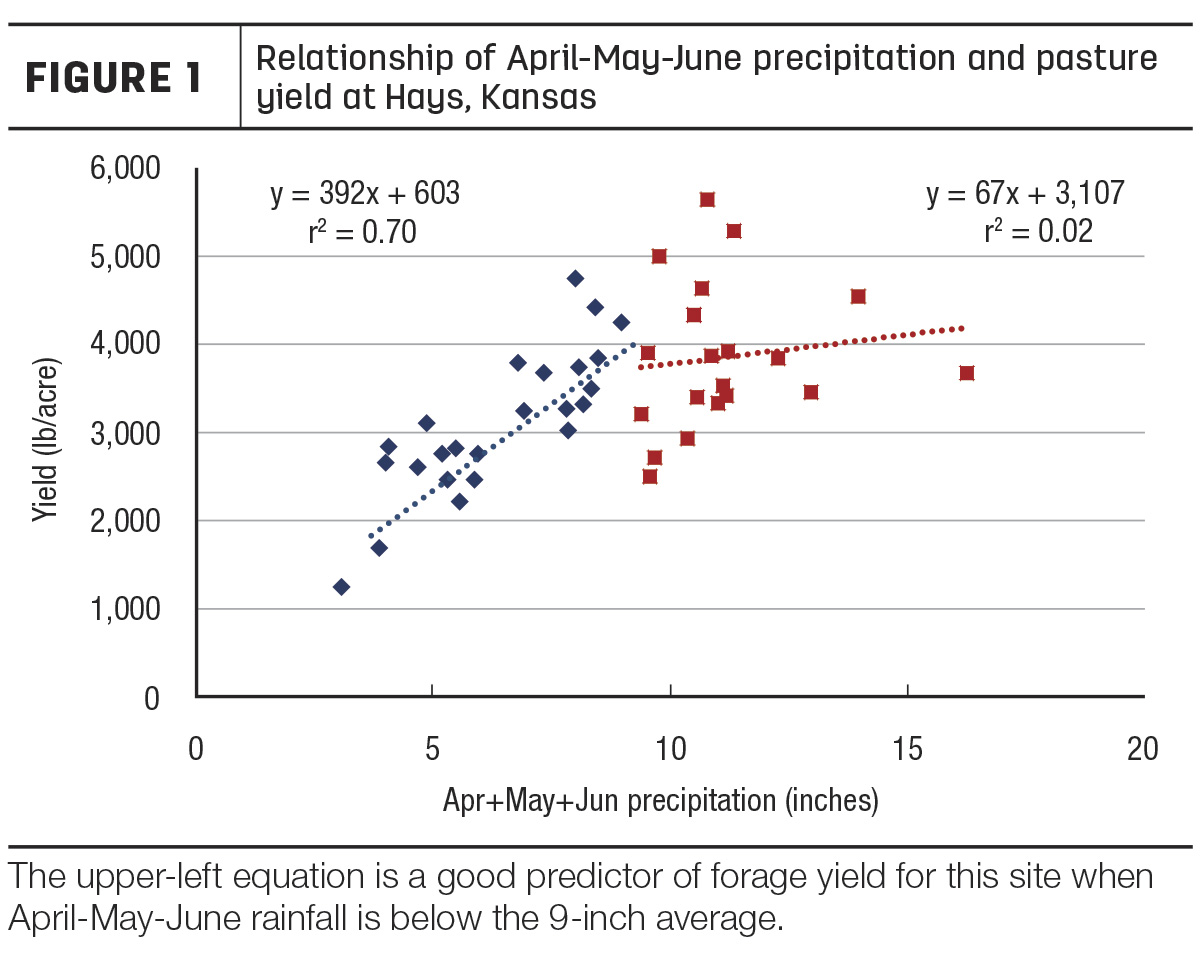

Data from the Hays Research Center indicates total forage production by the end of the growing season is unpredictable just from measuring winter precipitation alone. But comparing the average yield from wet winters and dry winters, starting the growing season with more soil moisture does slightly increase the average yield for the year. We are unable to reliably predict what the total yield potential might be from winter precipitation. May and June precipitation is a much better early predictor for end-of-year pasture yield. A recent summary of several central and northern Great Plains research locations also showed that May and June precipitation combined is a great predictor of annual pasture yield. Adding precipitation received in the month of April to the May and June total retains the high correlation with end-of-season yield, but also helps with early detection of drought and determining the probability of rainfall totals needed each of these first three months to reach expected forage production (see Figure 1).

For drought planning, predicting end-of-season forage production by the end of June is important to plan for stocking rate reductions, and having knowledge of the probability of low rainfall prior to June can help in detecting this shortage earlier.

It's hard to kill a dead man

Most of the previous rules of thumb address management during the growing and grazing season, but this rule of thumb pertains to management when most of the forage produced has gone dormant. It’s hard to injure or kill a dormant plant through grazing because the top growth is already dead. Photosynthesis and carbohydrate production are done. But this standing residual forage is still important and necessary to maintain soil cover for preventing erosion, promoting water infiltration and providing insulation for plant crowns.

During drought, pasture vegetation may go dormant during the growing season. In essence, these pastures have an early winter dormancy, and hopefully have enough carbohydrates stored that they survive through the summer and will make it through the winter. These pastures will also need enough stored carbohydrates to start good, vigorous growth next spring. Grazing this dormant growth during drought will not hurt the grass plant itself because the leaves had already gone dormant, but this may extend the water deficit if too little surface litter and standing residue is left to capture water when it falls again. For pastures that went dormant during the drought and were utilized to a greater extent, the lack of residue to start the next growing season may limit the amount of rainfall initially captured and delay or reduce spring forage growth. These secondary effects of grazing dormant forage may have an effect on future growth, regardless of whether or not dormancy is caused by drought or the onset of winter.

Take half and leave half

You may recognize this as an earlier rule of thumb. But it is important enough that it needs to be repeated. Go back and read all the rules of thumb.

The goal of this discussion was to modify earlier comments about rules of thumb to address drought. Digging deeper into these rules of thumb showed that some rules are better than others, which we hope will motivate you to evaluate your own “rules,” especially considering the current drought throughout the central Plains and elsewhere throughout the country.