If a person wants to crack open a walnut, a steam roller would get the job done but, in this case, overkill may indeed be overrated. Using the wrong tool obliterates the contents and makes the precious meat unpalatable. The outside becomes indistinguishable from the inside. You can’t tell where one starts and the other begins. A small nutcracker would be a better choice to enable the precision needed to extract the meat from the shell intact.

Using the right tool would allow the accuracy to do it, time and time again, with the desired result. As we know, that is what this fun little tool was designed for – separating the various components of a nut to enable a person to enjoy it. Remote sensing for rangeland monitoring can be seen in that same light.

Much like nuts and nutcrackers, there are many different needs in rangeland assessment and methodology. There are traditional methods (such as using tape measures and Daubenmire frames), government-provided coarse remote-sensing datasets and high-resolution remote-sensing datasets provided by private vendors.

Right tool, right job

If you simply want to get a vague idea of what is on the landscape and meet the base requirements of “monitoring,” you can use line transects and readily available coarse remote sensing and the various platforms that support it. However, if you need to dig a bit deeper to get at the “meat” of a question, while still retaining a wide-scale and accurate measurement of the area, another approach may be beneficial.

Using overhead photos and high-resolution remote sensing can be like using a nutcracker to crack a walnut. These methods can more precisely pinpoint variations in plant communities and plant density than the coarser methods. To achieve this, an overhead photo is taken using a boom attached to an ATV. At the end of a boom, a camera hangs with a specialized lens and a submeter GPS. The camera and GPS are then lifted off the ground approximately 10-12 feet to capture a photograph. This photograph represents a 6-meter-by-7-meter virtual Daubenmire frame of that exact space and time.

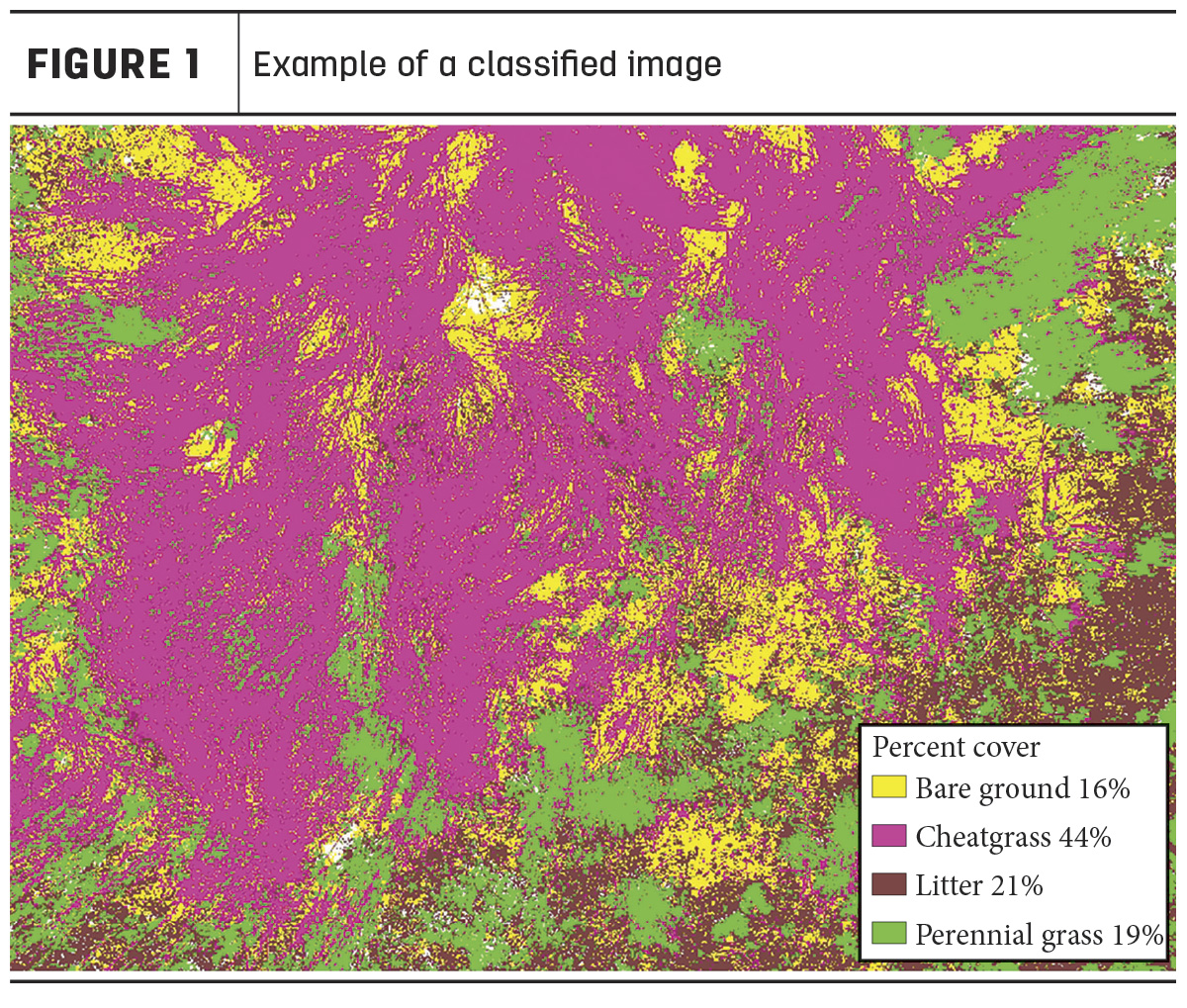

These photographs are taken in specific areas to represent various basic plant functional groups (sagebrush, herbaceous grass, annual grass, other shrubs, litter and bare ground). These images provide 24 million pixels of information for that specific place and time that will be used to create a classified image (Figure 1). In this classified image, every pixel is assigned a value that produces a precise percent-cover estimate for each plant functional group.

While the overhead photo is accurate, precise and visually appealing, the true power of the overhead photo is its ability to translate this site-specific information and its quality across a landscape using remotely sensed imagery.

'What does this mean for me as a land manager?'

Let’s assume you have cheatgrass on your ranch. It is scattered and only in isolated areas and in some places you may not even be aware of. If you are required to monitor it, tape measures and transects, or coarse government remote sensing, may be most applicable. If you are responsible for spraying, controlling and documenting success or failure, you may need a higher precision tool, such as overhead photography and precise remote sensing.

Managing cost

Any land manager wants to limit money spent on crews and supplies while ensuring the problem is taken care of. Most ranchers (and government entities) are on a tight budget. Wasting time and money is never the intention; however, the lack of reliable information can lead to just this. If I, as a land manager, had a continuous cover map, my estimation of the amount and abundance of cheatgrass may be very different from a more traditional rangeland platform. With a finer-scale prediction of landscape vegetation, I can save a lot of time and money. I may be able to more reliably pinpoint areas of the land that have cheatgrass and other areas that do not.

Landscapes are highly dynamic, and managers often struggle to obtain accurate enough information about what is happening from year to year. The need for reliable information is critical to be able to measure change over time, get a baseline or identify where problematic or beneficial species occur. There are all kinds of reasons managers need reliable information about a landscape, such as when dealing with endangered or threatened species or dealing with fire dangers to humans or structures. Some simply want their land to be as productive as possible. For example, managers may need to know where a critical habitat of sage grouse is on their land to design an effective fire abatement plan.

Conversely, managers may want to address a spreading invasive vegetation problem, such as cheatgrass, medusahead, Japanese brome and other problematic species that are spreading across the West. Whatever the issue is, we need accurate information that does not cost an alarming amount of money or take 20 years to obtain in order to make better, conservation-minded decisions to help ensure a bright future for generations to come.

The use of innovative technology, such as using overhead photos and remote sensing, can save time, money and (most importantly) help land managers meet their objectives. Whether it be for sagebrush cover for sage grouse credits, monitoring land for overall health, or targeting specific problematic or beneficial species, the use of precise remote sensing can be extremely beneficial. In the world of remote sensing, all tools have their use. It’s simply a matter of utilizing the right tool for the job.

.jpg?t=1687979285&width=640)