It was 20 years ago that the U.S. beef industry spun into unprecedented turmoil during a holiday break – all because of one cow.

The cow that stole Christmas.

What sounds like an innocent tale from the mind of Dr. Seuss unfolded on a global scale that turned U.S. beef production upside-down. Markets spun overnight, consumers were hit with media reports spreading shock and panic, government officials raced into crisis mode, trade partners closed borders to U.S. production, and industry leaders mounted a decade-long campaign to save the credibility of U.S. beef.

The cow in question was a dairy animal born in Canada and that milked at a Washington state dairy for years before going to slaughter. On Dec. 23, 2003, the cow initially tested positive for bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), also known as mad cow disease. It was the first documented U.S. case and exposed the world’s largest beef-producing nation to the most intense scrutiny seen before or since.

BSE had rocked the United Kingdom nearly a decade before that Christmas. The first case in Canada arrived several months before, bringing it closer to the U.S. For leaders of the industry looking back today, the BSE crisis is one with enduring lessons on how to prepare for animal health crises, how to react to media hysteria, and how science and information can make a critical difference in the 24-hour news cycle and even today’s digital age.

The following is an oral history of how leaders remember the cow that stole Christmas 20 years later. We've also put together a timeline of the events. Read: Timeline of events in the BSE crisis

Alisa Harrison. Courtesy photo.

Alisa Harrison, former USDA communications press secretary:

“BSE is something that the industry and the government had been preparing for forever since it began in England and it was determined we needed to be looking into the hard risks.

“My first week on the job [in 2001], we actually released the Harvard risk analysis for BSE that had been going on prior, which was something that Harvard looked at the whole cattle infrastructure and what are your risks for a BSE outbreak.”

Ron DeHaven. Courtesy photo.

Dr. Ron DeHaven, administrator, chief veterinary officer, USDA – Animal Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS):

“We had the benefit of the experience with BSE in Europe and in particularly the UK. We were close trading partners and were in frequent communication with our counterparts in those countries as they were dealing with it. So we had the benefit of what their experience was, and the dangers of making predictions when you didn't have all the science, which is kind of a trap that the UK fell into. And also, Canada diagnosed their first case a few months before we found our first one, so I worked very closely with the chief veterinary officer (CVO) in Canada as they were dealing with it, and he was quite helpful in giving us some guidance when we found the case in the U.S.”

Research showed the spread of BSE originated from feeds with infected protein prions being consumed by ruminants. From there, BSE could remain dormant in livestock and be manifest years later with the erratic and weakened state of cattle, hence the term “mad cow disease.”

The USDA acted in 1997, largely based on UK’s BSE struggles, to ban the feeding of ruminant protein feeds to other ruminant animals.

DEHAVEN: “We knew that the disease was transmitted by prions in infected feed or prions in feed that was then fed to other animals. So we had a pretty good understanding of how it was transmitted. And we had implemented a surveillance program in the U.S. where we were testing a relatively small number of animals, but we were looking at the targeted population, mainly older cattle – 5-plus years of age – that were showing some clinical sign that would be consistent with BSE.”

Canada’s announcement of BSE on May 30, 2003, raised flags throughout the U.S. beef complex, given the strong trade and production links between North American partners. The USDA boosted testing of possible BSE cases to around 20,000 to 40,000 animals. But the risks still seemed low.

DEHAVEN: “We had a pretty good appreciation for the fact that if the disease was present in the U.S., it was at a relatively low prevalence level, not that many cattle were affected.”

Chandler Keys. Courtesy photo.

Chandler Keys, NCBA vice president of governmental affairs, 1994-2004:

“Canada, we kind of knew early on because so many genetics, so many live cattle come from the UK, and from continental Europe into Canada. [We were] working with the Canadians to try to knock this back. Every down animal we were testing and every suspect animal. The Canadians were testing very extensively for this prion, and that's kind of how we found it.”

Dec. 23, 2003, was a Tuesday. In Washington, D.C., Congress was on recess. With an election year approaching, the Bush administration had a good month thanks to U.S. forces’ capture of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein just 10 days before.

The work week had already lagged to a slow pace. Agriculture Secretary Ann Veneman was hosting family that week and ready to attend A Christmas Carol at Ford’s Theatre. But first she went to the White House to help with a taped Christmas reading for first lady Laura Bush.

Ann Veneman. Courtesy photo.

Ann Veneman, U.S. secretary of agriculture, 2001-05:

“I had a whole day planned out, and I pretty much was going to take off a whole week. We were just going into the White House [cafeteria] after having done the little event, and my phone rang and it was my chief of staff saying, ‘We think we have our first [positive] cow. I said, ‘Gather everyone together, start to make a plan.’ I sent my family on to the play and then got back to my office.”

HARRISON: “The furthest thing from my mind is that we would have a case of mad cow disease because the industry and the government have been working on it for over 20 years and had put in some pretty key mitigating factors like the feed ban [in 1997]. It had been such a while since Canada had any cases. So I was surprised when I picked up my phone on December 23 and APHIS was on the line and said we had a presumptive positive.”

DEHAVEN: “I was actually at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum annex at Dulles Airport with family who were visiting. And I got a call from one of our associate deputy administrators that, ‘Hey, we have a presumptive positive case,’ and they had initiated the confirming testing at that point.”

Bobby Acord. Courtesy photo.

Bobby Acord, USDA-APHIS chief administrator:

“Well, I was not really surprised. We had a thorough response plan developed and done at Harvard to do a risk assessment and we had a communications plan worked out as to how we're going to respond, how we would communicate and what actions we would take. We had practiced that. We had regular calls with industry and among the government agencies affected like Food Safety Inspection Service. So we had a plan, and we work the plan, and it worked.”

The secretary returned to meet with a team that included Acord, DeHaven and others. An issue arose over whether the USDA should announce the news given that National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Ames, Iowa, said the brain tissue sample from the Washington state cow was presumptive positive. Protocol dictated to wait the five to 10 days for confirmation from the reference lab in Weybridge, England. Experts from APHIS and FSIS weighed when to release the existing information.

VENEMAN: “When I was ag secretary in California, we had two big food safety crises, both of them involving strawberries, and we lost a lot of market, particularly from the first one. I knew you had to get out there and get in front of these stories. But a lot of the scientists, they wanted to wait.”

Federal law prohibits any inside information from agencies be shared with industry. An investigation later by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission after the crisis found no information was leaked. But the industry was hearing information that some kind of case had emerged, prompted in part by the cattle markets.

VENEMAN: “I got back and started to get briefed by the group. I listened to what they said. And I said, ‘How sure are we?’ Then we got word that markets were beginning to move. So there were rumors out there, and I said, ‘We’ve got to get this thing out there.’”

KEYS: “The [NCBA] office was empty except me. There might have been a couple of staffers, but no senior people. Then I get the phone call from USDA, from the secretary's office, ‘We have found a positive cow.’ And it just was like, 'OK, now we've got to implement our crisis management plan.' The first thing we really focused on was getting in front of the media and telling the story and in making sure that everybody was on saying basically the same thing.”

Dan Halstrom. Courtesy photo.

Dan Halstrom, former trade official for Swift & Company, now CEO of U.S. Meat Export Federation:

“We had heard a rumor. There weren't many people in the office. I was in the office, as it turned out that day and our CEO at the time was in the office and just a few other people because a lot of people were on holiday already. And my immediate thought was, 'Well, things are going to be shutting down relatively quickly, internationally.' A million things started running through your mind. What can ship? What can't ship? What will happen? All that sort of thing, so it was rather eye-opening at the time.”

At 5:30 p.m. in Washington D.C., the USDA opened its press conference to available news networks. Veneman, still in the green Christmas blazer she wore to the White House holiday event, reported the first presumptive positive case of BSE “was tested and retested” at the Ames, Iowa, lab using immune-histochemistry protocols, “the gold standard recognized by the World Health Organization.” With DeHaven alongside, Veneman reported the quarantine of the cow’s original farm and the investigation at the plant where the meat was processed.

“Even though the risk to human health is minimal based on current evidence, we will take all appropriate actions out of abundance of caution,” she said.

Additional details were given about the pending confirmation from Weybridge, testing protocols across the U.S. and the response plan years in the making. Dr. Elsa Murano of the USDA answered questions about BSE, variant-Creutzfeldt Jakob’s disease (vCJD) and any risks to the human health population.

DEHAVEN: “The challenge became one of communicating the relative risk without diminishing the importance and the visibility to the public. So we felt pretty confident that the public health risk was very low. And yet you don't want to convey a message that you're not concerned by saying a risk is low.”

VENEMAN: “We wrote this speech for me, and we went back and forth. I wanted to put in the part that I was having beef for my Christmas dinner. I'd already purchased it. They said, ‘Oh, you better not say that.’ I said, ‘Well, it's true though.’ So I did, and of course that was the quote that made it half across the world.”

Media coverage saturated the news waves and headlines across the country headed into Christmas. Online news coverage hit immediately on cable news sites online. Two fronts of media response were common: One by the USDA and regulatory agencies, and a second from industry leaders in NCBA, producers and beef processors. The common questions surrounding a daunting label like mad cow disease were whether beef consumers could get the human variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob’s disease from BSE, and if the supplies of U.S. beef were safe to eat.

KEYS: “I would say the American public was paying sharp attention to this. Because the media was reporting extensively, and everybody was home. What do you do when you go home on Christmas? You watch a lot of TV, sit around with your relatives and family. And on big holidays, eating beef is a big part of Christmas tradition in this country.”

ACORD: “Considering the paranoia that existed with regard to BSE, and I will always remember that stumbling Holstein cow that showed up on CNN every time you’d see them talking about it and the word 'mad cow' was mentioned, it was not too surprising. It created some angst among the public. But really, we didn’t have bad public reaction to BSE, we really didn’t. We saw a drop in export markets, but the [domestic] consumption stayed pretty consistent with what it had been.”

DEHAVEN: “My kids were giving me a hard time at the time about how much repetition I was getting in terms of the questions being asked by the media. But I really looked at each repeated question as another opportunity to get that message out and clarify for the public that this is a crisis. We're dealing with it. We have the safeguards in place to protect human and animal health. And what we were going to do going forward with our surveillance program and testing to really confirm that our system was working.”

KEYS: “We knew that we all had to help coordinate this and totally tell the unvarnished truth to the public that the risk factor was here. People were predicting that tens of thousands of people were going to get this disease from eating meat. And we're like, ‘No, you won’t.’ We couldn't understand where that was coming from it. I think the people that were pushing that out there were not really caring about the truth. They were trying to scare people. And our job was to tell people that quite frankly, there's no brain in your hamburger. I mean, it got down to things like that. There's no specified risk material in your product.”

DeHaven and others routinely explained that the cow in question was part of a dairy herd in Washington. When it began exhibiting signs consistent with BSE, she was shipped for slaughter, tested and found positive. Although the cow originally came from Alberta, it had lived on the U.S. farm for several years. Animals become infected early in life when they're fed animal protein as young calves. With an incubation period of five to eight years, the animal may not show positive signs for years.

DEHAVEN: "So we felt confident that she had actually consumed the prions that caused her to have the disease while a calf in Canada, and just was incubating during that interim period between when she was exposed and prions tested positive several years later.

"What was so critically important was that we were able to say that those tissues that represented a human health risk had been removed and didn't enter the human food chain. And we also knew that none of her protein would have ended up in animal feed either, so there was no chance for spreading to other cattle because it doesn't spread before they die. It only spreads if you feed protein from that infected animal to other animals. So that there was no risk there."

HARRISON: “The fact that the consumers and the industry were able to hear from U.S. government and not some rumor, I think was just so important and so key to everybody staying as calm as they could be. It did disrupt our Christmas holidays. But that really was a big advantage for us because a lot of Congress was out, and don't take this the wrong way, but a lot of other reporters around the town as well. We were getting a lot of second-, third-tier reporters. They even sent interns who are covering the desk while the key reporters were away. So they just didn't know a lot about BSE, and so we were able to spend good quality time educating them about it.”

Days later on around Dec. 25, DeHaven received a midnight call confirming that the cow in question was originally from an Alberta herd. The fact that BSE can be dormant in younger cattle and be manifest in cattle later in life was something the agency was trying to reportedly explain to the media.

A view of Sunny Dene Ranch in Mabton, Washington, where the first BSE dairy cow in the U.S. was raised after birth in Canada. Courtesy photo.

DEHAVEN: “We had this unrealistic expectation that once we went public that this cow came from Canada, and it wasn't a U.S.-origin animal to begin with, that the crisis would go away. Nothing could have been further from the truth. It didn't matter to the public that she was Canadian-origin, or that most animals become infected very early in life so she would have become infected in Canada. The only thing that was important in the eyes of the public and the media was that she was in the state of Washington when she was diagnosed as positive.”

While the USDA continued its daily press briefings with DeHaven answering questions from national and foreign press, Keys and industry leaders at NCBA and the North American Meat Institute worked in concert to give accurate information from producers and from the USDA experts. On the international front, supplies of beef headed overseas were suddenly in limbo based on the closure of foreign markets.

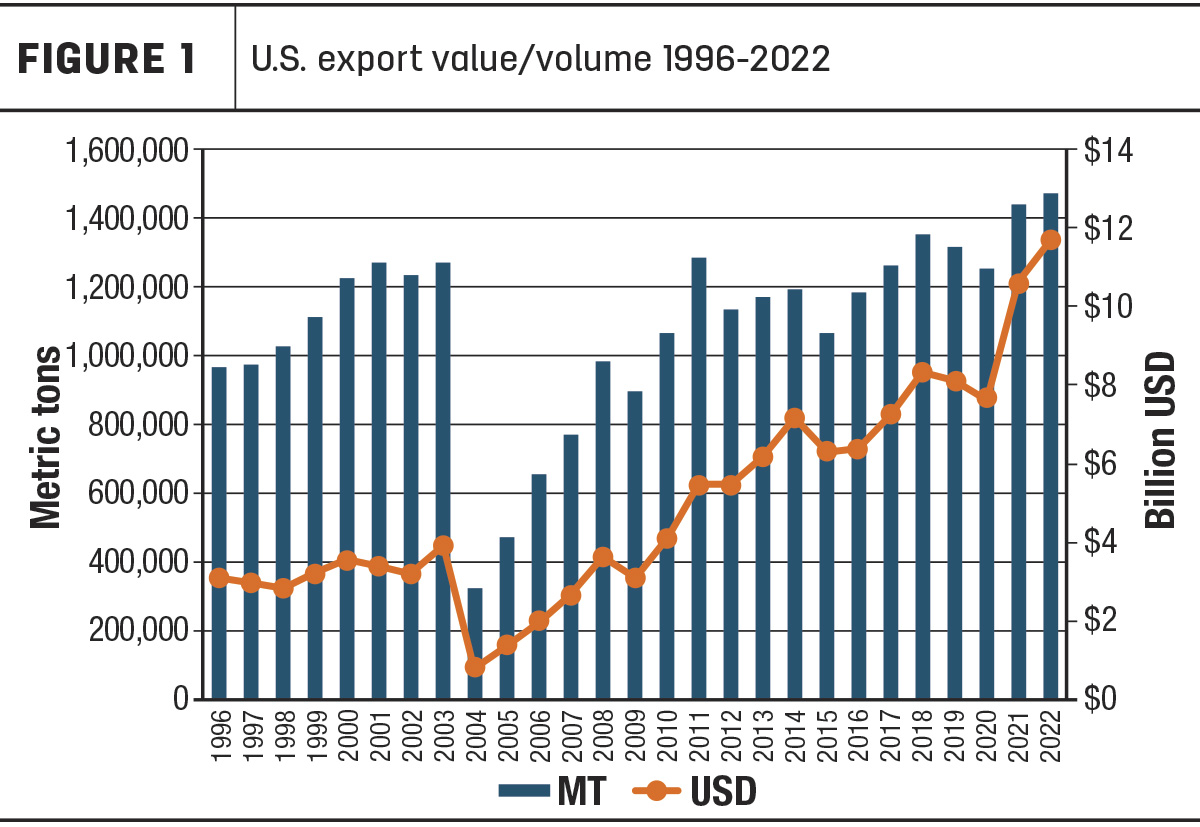

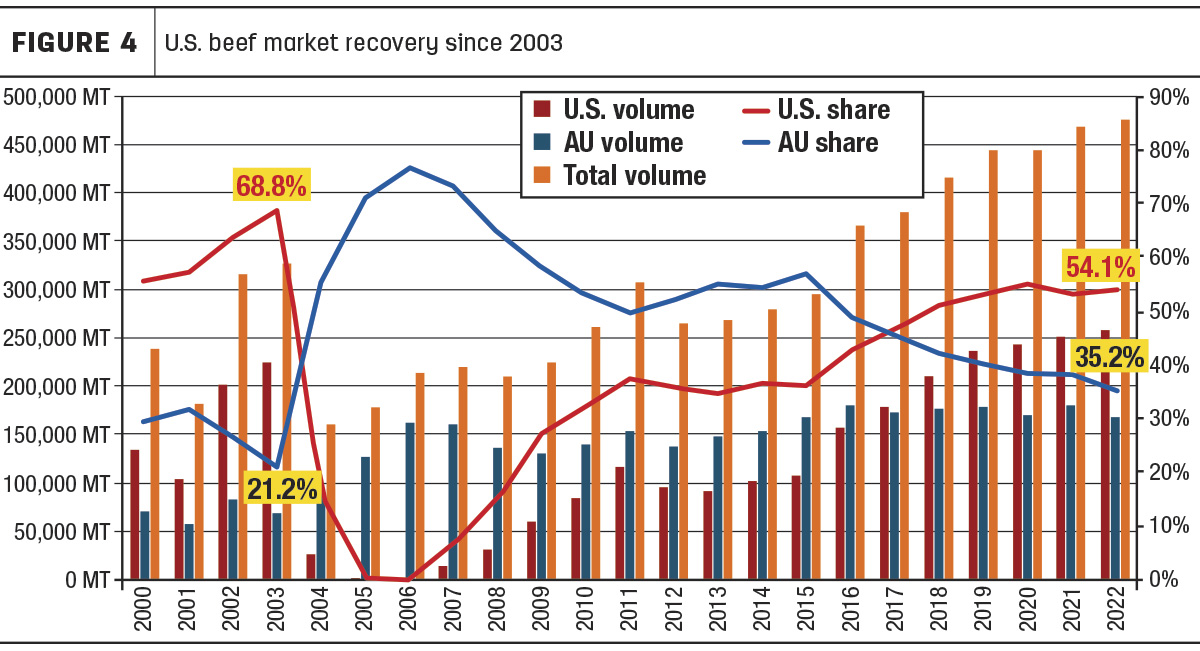

HALSTROM: “Every country was a bit different. What happened on this side of the ocean, everything just stopped. Inspectors were not signing documents to ship new cargo out. Cargo that was on the water remained on the water because it was already gone with documentation that was approved at the time. You don't stop stuff that's on the water, but I mean, you could but it would probably stop at the first port of call, if there's more than one port of call. So honestly, the whole situation was so chaotic that it took literally weeks to figure out the short-term impact of what can go where and what can't and won't be held up. Then it literally took months to figure out the pipeline. literally months, especially in larger markets that had a lot of volume like in Japan and Korea.” (see Figure 1)

As more information emerged through the week and daily news conferences, the USDA made another decision on Dec. 30, 2003, announcing that all injured or “downer” cows would be eliminated from the food supply. The announcement wasn’t fully embraced by some industry insiders and members of Congress from cattle states.

HARRISON: “We all know about downer cows. I think the arguments not to do it were valid. But when you looked at what we learned from the English experience, and that we believe the first cow in Canada was a downer and that this [cow] probably was since we didn't know the full scope yet, it was the right decision.”

KEYS: “My reaction was: 'Let's do it.' I mean, that's why we have veterinarians at the slaughterhouses to look at the animals, to make sure that they don't have any manifested problem when you're just looking at them as live animals right before they go to their demise. You got the vet saying, ‘OK, that animal’s healthy enough to be slaughtered for human consumption.’”

Veneman, who left her first stint as deputy administrator of the USDA in 1993, months before the E. coli crisis surrounding Jack in the Box hamburgers in Washington state, knew the downer cow issue would be critical among consumer groups.

Courtesy photo.

VENEMAN: “Some of the cattlemen weren’t happy with things we were doing, like [removing] the downer cows. We knew those were some of the riskiest cattle for BSE because they tend to be the older cows, many of which were spent dairy cows, as you know … The industry was going to have a lot of trouble if we found a lot of this product has gone into the food chain; they were going to have a drop in sales. So they have an economic interest in taking the right precautions. And then of course, the consumers, you want to protect the consumer.”

KEYS: “The downer cattle issue was one of the things that unless we put it behind us, it was going to be in a problem in the future. I can always tell when public policy leaders, government officials or the press, or whoever, if they don't like something, they want people to pass over it. Then you say, ‘OK, then you get in front of the American public and you tell them that these downer cattle are OK to eat.’ Of course, they don’t want to do that.

“We don't have much of a problem at all in non-ambulatory or downer cattle at the fed level. This is a cow issue and we needed to deal with the cow issue. Dairymen and cow-calf operators got the message pretty quick that if they took a non-ambulatory animal to town … . It would be immediately euthanized right there at the barn … Once that became reality, you just saw the non-ambulatory animals drop off exponentially.”

The move to restore U.S. beef against BSE required testing, lots of it. The long road to reopening trade agreements and global markets was hashed out through months, even years, of negotiations. In the case of some of the U.S. biggest partners, opening trade would take more than one attempt.

HARRISON: “The fact that traceability wasn't automatic, it created an emphasis to finally do maybe do a mandatory animal ID program, something that USDA was on the verge of doing. But it got such resistance from the industry, that it didn't go forward…. Whenever you mandate something with a hammer, it just never really works. You can't have an animal ID program unless you have support from the industry.”

HALSTROM: “Leading up to December 2003, we were on a heck of a roll. International growth was extremely brisk. I remember the growth into Korea and Japan, especially Korea, was record-breaking for that time.

“We came out of BSE thinking as an industry, we'll just get full access back the way it used to be. And this does take a little bit of time but shouldn't take too long. Looking back, that was a mistake. We had to understand what BSE was, and one of the misperceptions was that it was a food health issue. But it was an animal health issue, not a food health issue. At the time we didn't know that, so it made things even more complicated.”

Ji Hae Yang. Courtesy photo.

Ji Hae Yang, vice president, U.S. Meat Export Federation, Asia Pacific Office:

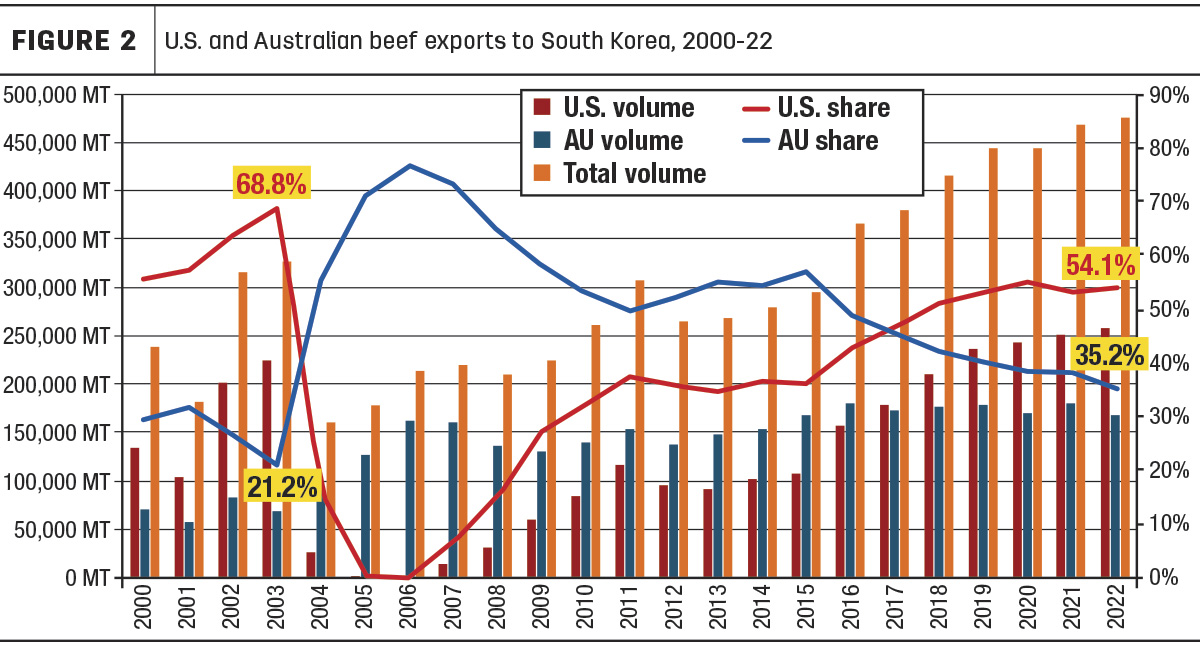

“Korea has a high preference of grain-fed beef, so without the supply of U.S. beef, Korea could not source the high-quality beef from another country. Our market share back then was almost 70 percent imported beef, and our self-sufficiency rate is just over 30 percent. So that means 50 percent of beef came from the U.S.

“That created a momentum for Australia to invest more on the grain-fed beef production to meet Asian demand, including Korea, and also to Japan and Taiwan. So that before 2003, Australia just exported the most grass-fed beef, and then gradually they increased their production on the grain-fed beef. During the absence of U.S. beef, Australia became the biggest supplier for beef to Korean market.” (see Figure 2)

U.S. trade officials soon determined their North American partners had to come first. Canada was far more reliant upon exporting its supply – around 37% of its production, compared to the U.S. which only exported 9%. Getting Canada to be on the same page for testing and protocols was an easy first step.

KEYS: “It was in their best interest to align themselves with the U.S. So the Canadians came around pretty quickly. They were more than willing to help tamp down the fire. Then we had to get to the Mexicans pretty quickly and work with them to see what they wanted to do.”

Since the enactment of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, beef tariffs to Mexico went from 25% to 0, and dialogue was better than ever in the decade after.

KEYS: “Thank God, we had those really strong relationships after NAFTA. Because I can't imagine what would have happened on BSE, or any other animal diseases, if we had had a confrontational or we’re in a position fighting with the Mexicans over trade issues, which we had in the past up until NAFTA. They got onboard pretty fast.”

Restoring access to Japanese trade, however, became “a hard nut to crack,” as Keys explained. The biggest hurdles beginning 2004 and onward were the testing requirement for cattle, and the age restriction to accept beef only 20 months and younger. When the doors to exports closed on Dec. 24, 2003, it sealed off $4.8 billion in foreign trade – half of which, $2.4 billion, was going to Japan and South Korea.

In the case of Japan, the demands reached a level that the U.S. trade reps and scientists couldn’t get their trade partners to lower.

DEHAVEN: “The whole story of those discussions had gone on for a period of months, particularly with the Japanese. The Japanese finally said, ‘If you will just start testing every animal at slaughter, we’ll lift the ban.’ Well, you have to understand that most cattle in our country are going to slaughter between 18 and 22 months old. And this is a disease that has an incubation period of typically five to eight years, and the test will not show positive until just shortly before the animals develop clinical signs and eventually die. So testing animals at that age had no public safety value whatsoever.”

ACORD: “I don't know that there was a question or concern about the validity of the test. The concern was the cost of testing every beef carcass that we wanted to ship. And if you were going to test towards going into the export market, you surely would have had to test within the domestic supply chain as well.”

Testing each animal would cost $30, and when multiplied by 35 million head slaughtered, that equaled $1.05 billion. The pressure was immense from government and industry to get the ball rolling for Japan, with Korea soon to follow if Japan opened. DeHaven and his team felt other countries hit by BSE would be compelled to do the same costly test to meet export partners’ demands.

At the time DeHaven’s animal health unit reported to Acord, the USDA-APHIS administrator, who oversaw all five divisions. In testimony before a House committee about the BSE testing, Rep. Maurice Hinchey (D-New York) and some others criticized the USDA for what they perceived as a lack of testing.

ACORD: “It really wasn’t a partisan issue. It was pressure being put on the administration, the Bush administration and the secretary to [satisfy] some of the exporting companies that wanted to quickly get back into the export market where we were cut off from Japan.”

DEHAVEN: “When it looked like the administration was going to make the decision to do this testing, [Acord] resigned. He went in to see Secretary Veneman and said, ‘I cannot be in charge of this agency at the time when it makes a decision to go ahead and do this testing that not only has no scientific value, it provides a false sense of food safety security that really isn't there.’

“Well, his resignation caused the secretary and hence the White House to reconsider, and I’m really pleased to say we at that point decided not to do that testing. And it ultimately took us over 10 years to recover all of that lost export market. But we did so because we did the right thing for the right reasons. It just didn't make sense to do this testing.”

Acord insists his exit was also timed with his retirement and to step away to care for loved ones in poor health. But he doesn’t regret his stance to not push the higher volume of testing.

ACORD: “The fact is: Had we started testing, it would have cost billions, billions of dollars and we would probably still be testing today because we would have created a standard to do that. We never believed that was necessary. There was a lot of pressure to do that, particularly from one company who wanted to have their own lab. We decided that we were not going to approve the lab. We saved billions of dollars by taking that approach.”

With Acorn's resignation in March 2004 after 37 years at the USDA, DeHaven was elevated to the chief administrator’s role. Even upon rejecting Japan’s demands, APHIS still pushed to increase more testing after an international team of advisers came to the U.S. and made suggestions about the U.S. testing frequency using examples from European countries.

Not all the recommendations were feasible or even realistic. But one, to test 20,000 normal animals at slaughter at a cost of $600,000, began to catch momentum. DeHaven, in his new role, voiced his opposition to the idea. But Veneman determined that if the U.S. refused the board’s recommendation, it would create a hostile perception of the USDA’s program.

DEHAVEN: “And the fact that we did the testing, and of course all 20,000 tested negative, added some validity to the science and also that our program was based on science. From a PR standpoint and the relationships with our trading partners, it was 600,000 dollars well spent. But I was not looking at the bigger political picture at the time. So it cost me a lot of political capital with the secretary when I pushed back on that, but it was a good lesson for me.”

After Bush won his reelection in November 2004, Veneman prepared to leave after the first term. The president nominated Mike Johanns, Nebraska’s two-term Republican governor, to be the next USDA secretary. Johanns had a string of successes on trade missions for his state, notably in Asia. As he went into confirmation hearings, members of the Senate began pushing him hard on how to get Japan back in the U.S. beef market.

Mike Johanns. Courtesy photo.

Mike Johanns, U.S. secretary of agriculture, 2005-09:

“There were pretty clearly marching orders from the Senate. And it was very clearly at the top of the agenda from an ag policy standpoint for the president. So yeah, I came to office really feeling like I needed to make some progress here and do so as quickly as I could.”

The situation wasn’t just about Japan, however. Johanns quickly learned that the partial opening to Canadian live cattle created a dichotomy for trade policy. Canada did not have full access because many in Congress and the industry didn’t think BSE testing was satisfactory in that country.

JOHANNS: "Virtually every country, not just a few, closed their market to U.S. beef. Most notable would be Japan. That's one that gets the most attention simply because they were a very large buyer of U.S. beef. On the other hand, we had closed our market to Canada. So trade flow, basically it stopped.

“On one hand, I'm out there pushing countries in every way I could to get markets reopened. And yet they would often push back at me and say, ‘But you're not doing that. Why should we?’ And so, you know, it was a very delicate diplomatic situation. And then there was a divided viewpoint in the United States. Some groups did not want the market opened at that time, and they were concerned about more BSE [from Canada] coming into the United States.”

The USDA initially set March 7, 2005, as the date when trade would resume with Canada. After Canada discovered two more cases of BSE in early 2005, Johanns took a USDA team to study the testing system and reported that Canada had a robust inspection program, overall compliance with the feed ban was good, and transmission was being reduced. “Where isolated issues were found to exist, they were related mostly to areas of documentation and recordkeeping," the USDA reported.

But the critics already sprang into action. The cattle protectionist group Ranchers-Cattlemen Action Legal Fund (R-CALF) filed a lawsuit to stop the USDA’s rule to open Canadian borders, saying the policy violated public hearing procedures, and asked for an injunction in February 2005. A federal judge in Montana agreed, allowing the injunction to take effect against Canada.

Making matters more difficult, the Senate then jumped on the same protectionist bandwagon, voting 52-46 on a measure opposing the reopening of Canadian imports. Johanns remained undeterred, and the USDA quickly appealed the Montana federal court ruling in the R-CALF lawsuit.

JOHANNS: “What was happening with the Senate is: They wanted everybody to buy our beef. They just weren't as keen about the idea of reopening to other markets. Canada was the one that got the most attention ... The perfect world for many was, 'This will be very one-sided, and we'll get all of these markets open back up, and they’ll be buying our beef. and yet we'll be able to keep everybody else out, specifically Canada.' And you know, it just simply doesn't work that way.”

After two years of testing, USDA science officials were even more confident that the safeguards were working in the U.S. More than 750,000 tests of slaughtered animals had been completed in a period under two years, all targeting older livestock that displayed some clinical signs consistent with BSE.

DEHAVEN: “We really had a good handle on the fact that even if it existed in the U.S., the prevalence was very low. And there was no geographical distribution based on that testing. So it would have been probably 18 months to two years before we could really profoundly say we have a system in place and based on this surveillance, that the prevalence of the disease is very, very low.”

The U.S. District Court injunction to keep Canadian beef closed to the U.S. was overturned on July 14, 2005, by the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. The same day, the USDA’s order allowing live cattle from Canada 30 months and under went into effect.

Limited trade did eventually open to Japan in 2006, but not without hiccups. Exports resumed in December 2005 to boneless beef aged 20 months and under. That was revoked a month later when shipments didn’t pass inspection. The ties were established again that July with the same restrictions on age and removal of specified risk materials.

JOHANNS: “I knew that we were going to have to get to a point where trade for beef was normalized. The science very, very clearly said that if you banned ruminant-to-ruminant feeding, which Canada had done, and we had done, and other countries had done, that eventually, except for an unusual variant, BSE should for all practical purposes disappear. Once that was established, for me, it became very clear that BSE was not going to be an issue in time. And that's really the case today.”

More drama on the Asian trade movement was happening on the political terrain in South Korea. In spring of 2008, President Lee Myung-bak’s administration began finalizing a deal that would bring both boneless and bone-in beef, including those from cattle 30 months and older, into Korea – ending its trade restrictions on U.S. beef. But political opponents criticized Lee, a former executive at Hyundai, saying he was bowing to U.S. beef demands in exchange for Korea's access to sell cars in the U.S. Consumer groups lashed out, sparked in part by a controversial network news program.

Protesters rally against U.S. beef exports in Seoul, South Korea, in summer 2008. Courtesy photo.

YANG: “So back then, the information source was very limited, and it was just the beginning of social media. Most people did not have capability to identify which is fake news or the true story about the BSE. There is one national TV station called MBC [Munwha Broadcast Corporation], and it purposely made a program [on news report PD Note] that intentionally mixed the definitions of vCJD and CJD. It created a great level of fear for the Korean consumer. They had a belief if they ate U.S. beef, they immediately contracted vCJD. And the Korean consumer doesn't understand the difference between vCJD and CJD.”

The PD Note program was titled “Is American Beef Really Safe from Mad Cow Disease?” In the news broadcast, subtitled images of U.S. cattle claimed they suffered from BSE when their injuries were from cattle welfare. Another program segment suggested a U.S. college student suffering from Wernicke’s encephalopathy was actually diagnosed with vCJD. More elements of the story warned consumers could contract CJD from other household products.

YANG: “It was kind of explosive at making all the general public come out of streets, and have a candlelight protest in downtown Seoul in front of the Blue House, the presidential residence. [Tens of thousands] of people had demonstrations every night with a candlelight. It continued more than 100 days. During the demonstration period many of the anti-government or anti-U.S. made the story of the fake news. And then students and moms are very easily mobilized by that kind of news. … One of the cartoonists made a cartoon [figure] to create a fear for the young students. They came out to the street and then held the signage that said, ‘I don't want to die after eating U.S. beef,’ something like that. So it was a very irrational period of time for the Korean consumer.”

While the MBC program was later investigated and apologized for its flawed reporting, the negotiations for U.S. beef to Korea went backward. Lee apologized to his country for not prioritizing health concerns, and the trade agreement was revised for beef under 30 months old and without specified risk materials. The same policy remains today, but it has not blocked U.S. beef from continuing to climb.

HALSTROM: “Politics definitely were involved in the Korean example of regaining access. But that's not limited to just the U.S. That potential aligns with everybody. I think our challenge at the time, and God forbid we have to go through something like that again anytime soon. But if we did, the focus should be trying to relay the facts and let the chips fall where they may politically, but with our USDA Foreign Ag Service in the lead.

“This is something I've really come to understand over the years, that one of our most reliable partners internationally when we're marketing U.S. beef or pork is working in concert with a Foreign Ag Service hosts in whatever country: Japan, Korea, Mexico, Europe, wherever. They do a wonderful job and they are the ones trying to relay the facts and try to divorce those from the politics that go along with it.”

Ten years after BSE, in late 2013, all markets that were closed to beef were again opened and on their way to record business. In 2022, Japan and Korea were again the top volume destinations for U.S. beef and variety meats, and two of the highest value spenders on American beef products, totaling $5 billion spent by the two nations.

More importantly, the presence of BSE in the U.S. and North America is so limited as to barely warrant news in today’s beef industry. Only six confirmed cases have occurred since 2003.

As new epidemiology concerns look on the horizon for avian flu, African swine flu and, perhaps most frightening, foot-and-mouth disease (FMD), the USDA and trade officials know the preparation must begin now for how to handle similar crises to BSE.

JOHANNS: “Foot-and-mouth disease is a disease of a whole different character. This is extremely infectious. Once you get it in the herd, it's just going to be a real challenge. So, number one, I'd be paying attention to what other countries are doing. Is our system robust enough where we can be confident of our protection, in terms of what's coming into the United States? The second thing, I just think preparation is so important. I just don't think you can prepare enough. And third, I would have the best scientists that I can find engaged on this problem, not only in the USDA but across the country. Ron DeHaven and [USDA chief veterinarian] John Clifford could speak in a language that people understood and came to trust. … I don't think these two gentlemen appreciate just how significant their impact was in bringing us through this.”

HARRISON: “If we had FMD today, we’d probably do OK. We could probably trace a lot of it. But you know, and this is me talking, if we get FMD, it’s going to be a small farm and someone who doesn't really participate in quality assurance or biosecurity credit calls. And so those are going to be the people who don't have all the record-keeping systems in place that the majority of those professional producers have.”

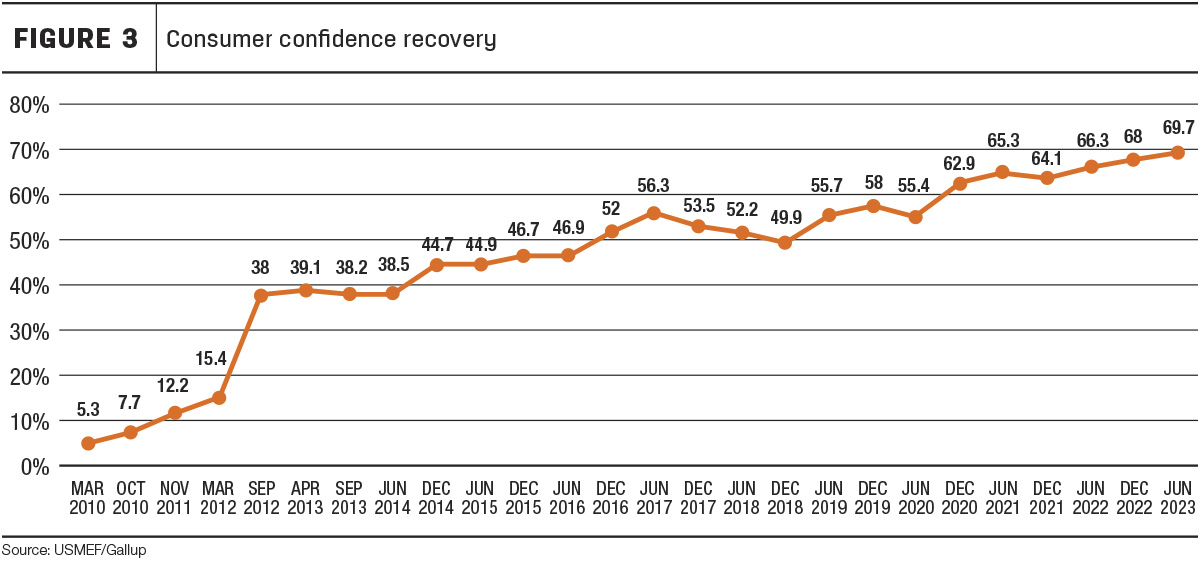

DEHAVEN: “Even after we had that first case, in December 2003, the polling that was being done by the industry suggested that consumer confidence in the safety of U.S. beef actually went up. …

"The last thing you want to do is get overconfident that you can handle anything that might come at you. But I think because of the historical agency focus on early diagnosis and rapid response to a foreign animal disease outbreak, or transboundary diseases, we are pretty well prepared for just that kind of eventuality.”