Picture this – it’s a beautiful day out in the dairy barn; cows are ruminating calmly in their beds, a gentle breeze stirs the air from a strategically placed fan and the rhythmic squeak of headlocks bespeak of ol’ Bess up at the feedbunk enjoying a healthy breakfast. As you stroll through the pen, your faithful nutritionist by your side, the tranquil mood is sporadically interrupted by the seemingly insatiable need to stop and schmear every steaming fresh pile of cow manure across the barn floor with a boot.

Ever wonder what it is with this fecal fascination? Think of it as “reading the tea leaves,” except with poop instead of leaves. While this excremental exploration may seem unsightly at the surface, manure can provide critical insights into the efficiency of digestion of the dairy ration. So, if you are not yet totally disgusted by this doo-doo deep dive, read on.

Manure condition and consistency

The first step in evaluating manure is just that – a literal step into a cow pat. Take a half step into a manure pile. When you remove your boot, if your tread pattern disappears, the manure is too loose. If the tread pattern looks like a perfectly cast reproduction of your Bogs, it is too firm. Somewhere in between? Now we’re getting somewhere.

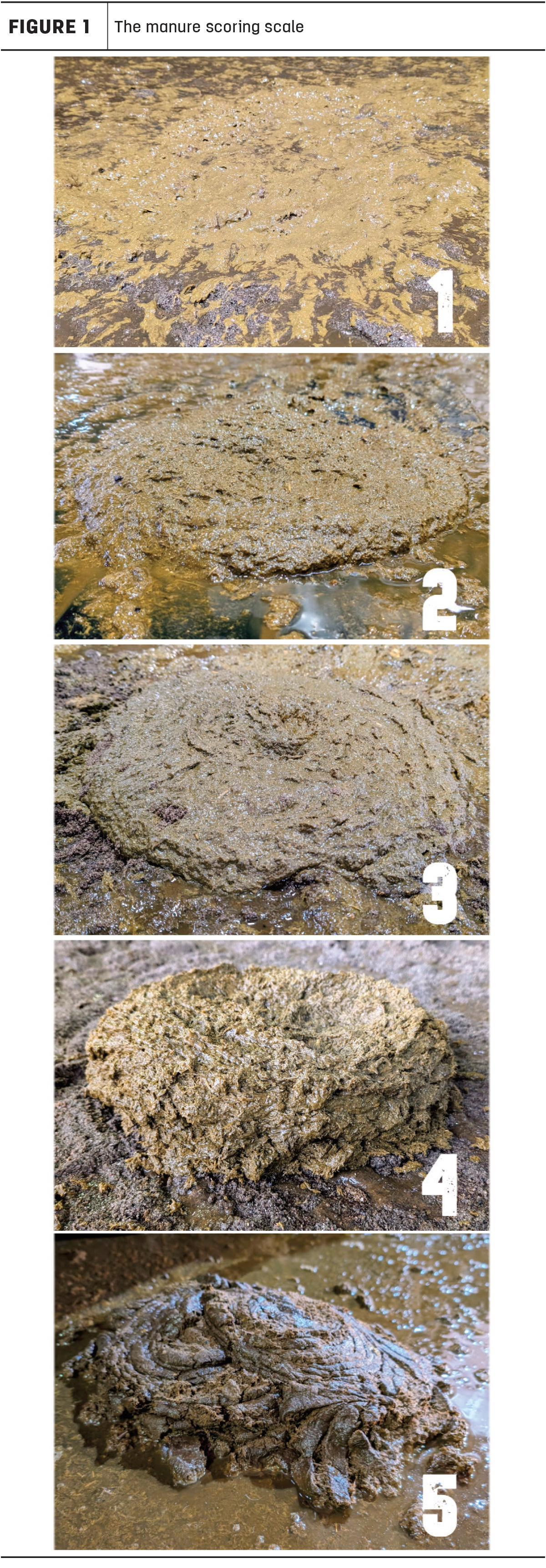

Taking a step further, nutritionists will often employ the use of manure scoring (Figure 1). Manure scoring operates on a five-point scale, a 5 being “brick” firmness and a 1 being “cows are repainting the barn walls green.” The ideal manure score for a pen of lactating cows is 3 – piles should be about 1.5 to 2 inches tall (around the height of your second knuckle), forming concentric rings with a small depression in the middle. Because of differences in diet and intake, dry cows will normally have manure scores of around 4.

Manure from a pen of cows should be evaluated for consistency. Are most piles alike or is there a lot of variation? Excessive variation in manure can be indicative of potential upstream issues such as sorting of the ration, slug feeding, lack of feed pushups, inconsistent feed delivery time or inadequate mixing, to name a few. Regularity is important for cows, too.

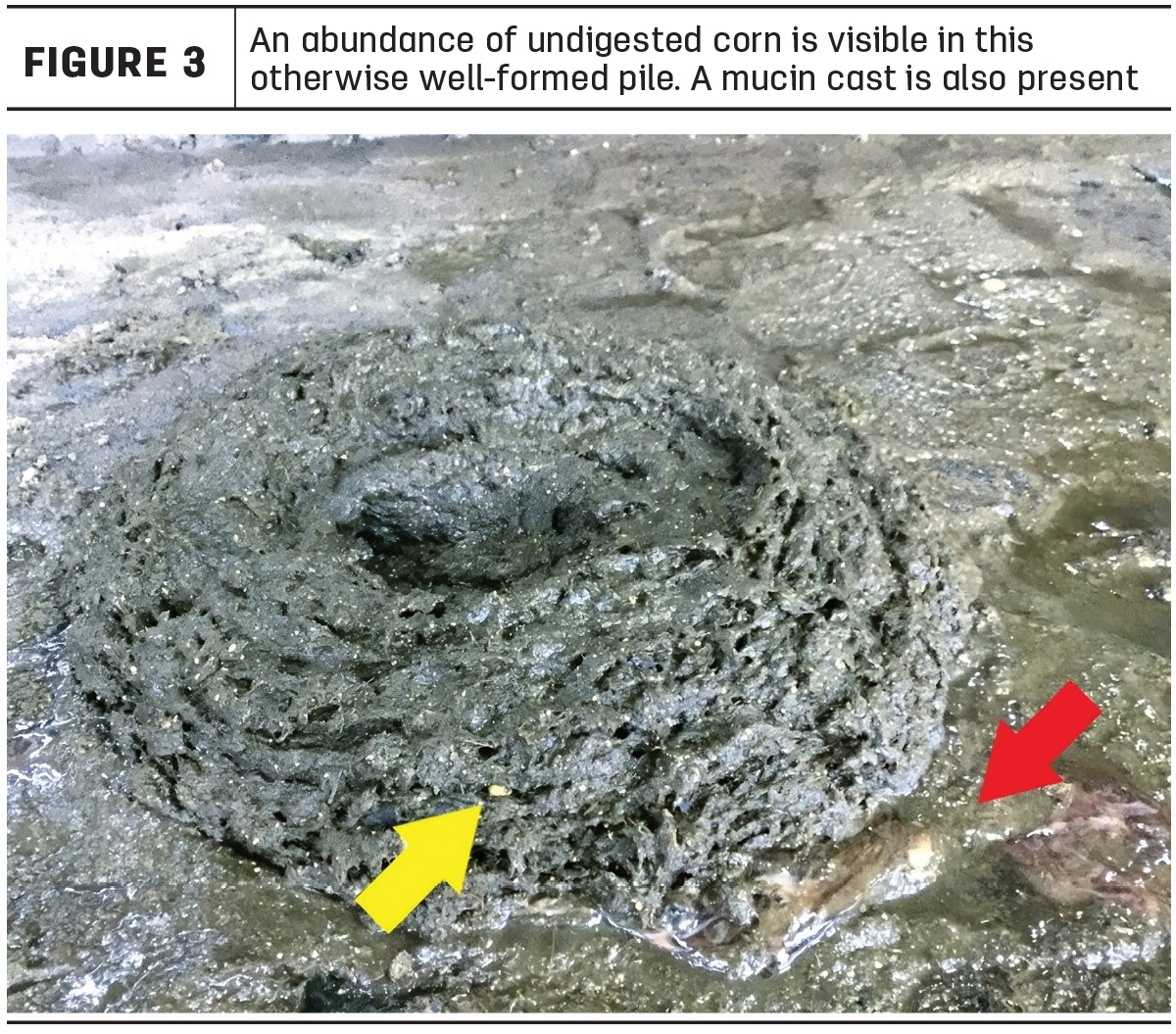

A closer look should also be given to individual manure piles. This is where the classic boot schmear comes into play. You may notice shiny, rope-like mucous that contracts after your boot sweeps the pile. This is called a mucin cast, which is sloughed mucous produced by the cells that line the intestine (Figure 2).

Intestinal cells produce this mucous for protection from adverse conditions, such as low pH resulting from excessive hindgut fermentation. Excessive hindgut fermentation occurs when the rate of passage is too high (not enough effective fiber) and/or too much starch is leaving the rumen undigested. Speaking of starch, an abundance of corn in the manure may be seen. If you notice piles containing gratuitous amounts of corn, sort of like a chocolate chip cookie in reverse, this is not good (Figure 3). Too much corn present in manure warrants further analysis.

Manure screen

The next level of our poo appraisal is conducted with a tool called a digestion analyzer or manure screen (Figure 4). It is akin to the Penn State particle separator but for after the TMR has left the cow.

The manure screen can give us insight into the extent of digestion with quantifiable results. It consists of three screens held inside of a cylinder, each screen perforated with holes smaller than the last. Manure samples are gathered throughout a pen and are washed through the screens with a hose. Next, the material remaining on the screens is wrung out to remove the water (gloves recommended) and is then weighed. Ideally, the majority (more than 50%) of the material is collected on the bottom screen. A build-up of material on the top and middle screens is often indicative of an imbalance between fermentable carbohydrates and protein pools in the rumen or excessive rate of passage through the digestive tract.

When performed regularly, manure-screen results can provide trending information. This information can be related to the effectiveness of ration changes and feeding management, which ultimately translates to milk production efficiency.

Moreover, issues with the digestion of individual ingredients can become apparent when manure is washed, such as whole cottonseed, raw soybeans and cereal grains. While zero pass-through should not be expected for most ingredients, seeing copious amounts in the manure warrants corrective action. Undigested corn grain becomes particularly evident – performing a fecal starch analysis is advisable to quantify potential issues.

Fecal starch

As starch is often a major source of energy for ruminal microbes and, subsequently, the cow, loss in manure represents a loss in productive efficiency. To collect manure for analysis, small samples should be collected from fresh piles and combined – forage labs will provide sampling jars specifically for this odorous task (Figure 5). Next, an often-overlooked step is to immediately cool and freeze the manure prior to shipping to the lab. If the manure remains warm, bacteria may continue degrading the starch, leading to underestimations of starch content. Finally, watch with a mischievous sense of gaiety as your postman wonders why your parcel smells as it does.

A baseline goal for fecal starch is less than 3% – a rule of thumb is that for every additional 1%, we miss out on about 0.7 pounds of milk. In conjunction with the value of milk, we must remember that corn is also worth something.

Using the fecal starch calculator provided by Rock River Labs, let’s consider a scenario in which a 1,200-cow dairy is valuing its corn at $4.80 per bushel. Assuming a dry matter intake (DMI) of 58 pounds and a dietary starch of 26%, reducing fecal starch from 5% to 3% represents a savings of about 4,600 bushels per year – worth over $20,000. That is a lot of dollar bills that could be floating out in the lagoon. If we capture the additional 1.40 pounds of milk (0.7 pounds x 2), we’d produce about an extra 6,000 hundredweight (cwt) worth – around $100,000.

While measuring fecal starch is easy, the challenge comes in reducing it. Some critical factors to consider include the extent of grain processing (particle size), the moisture content of ensiled grain and the magnitude of fermentation. Notice that these factors are already set into motion at harvest, highlighting the importance of careful monitoring when the choppers are rolling. Fortunately, there are some corrective actions we can take with existing feeds. For example, reducing dry corn grind size will improve total tract starch digestibility – a good target is around 300 microns. As painful as this sounds, re-grinding high-moisture corn that did not ferment (we call this “dry moisture corn”) is often worth the time and effort to improve starch digestibility.

On top of addressing the corn itself, adjustments to the total diet can improve starch digestion. First, elevated fecal starch can represent an imbalance between fermentable carbohydrate and protein pools in the rumen. Rumen microbes could have been supplied with inadequate levels of soluble protein needed to multiply, thrive and digest starch. It’s akin to my productive limitations in the early morning hours if I have been shorted a cup of coffee. Second, the source of starch supplied can be modulated to synchronize digestion rates with the use of fast starch sources, such as corn starch, cereal fines or bakery waste. Third, the rate of passage can play a role in the extent of starch digested. Starch sources need to hang around long enough in the rumen for the microbes to get a crack at them – providing enough effective fiber, often in the form of forage, is paramount.

If you’ve ever uttered the phrase, “Smells like money” in reference to cow manure, you are not wrong, and pristine patties can look like money too. Using manure condition, consistency and contents can inform upstream nutrition and management decisions to drive productive efficiency on the dairy.

.jpg?t=1687979285&width=640)