Face flies are pests of pastured livestock animals such as beef cattle and horses. The face fly is a robust fly that resembles the house fly in appearance.

Like the house fly, the face fly has a sponging type of mouth and feeds on animal secretions, nectar and dung liquids. Only the female face fly will be found clustering around an animal’s eyes, mouth and muzzle, and cause extreme annoyance and irritation. Livestock will react to fly feeding by bunching, seeking shade in trees or in some cases standing in water to avoid flies. Female flies also feed on blood and other secretions around open wounds.

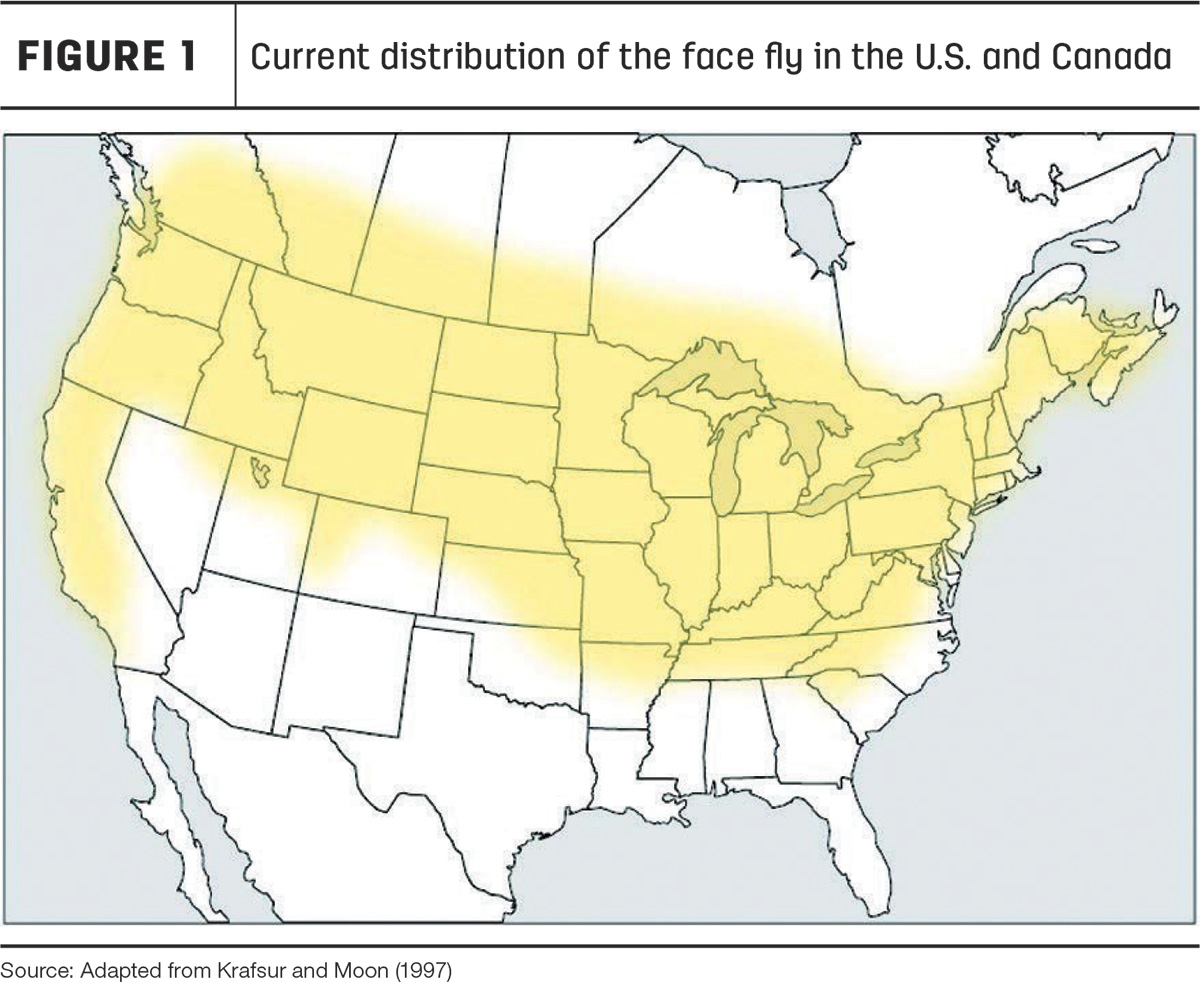

Face flies are present throughout the summer, but populations usually peak in late July, August and early September. They are more numerous along waterways, areas with abundant rainfall, canyon floors with trees and vegetation, and on irrigated pastures. These widely distributed flies are native to Europe and central Asia and now plague cattle and horse owners throughout North America north of 35 north latitude (Figure 1).

Pinkeye

As adults, females use their sponging mouthparts with prestomal teeth that rasp and scrape and penetrate the conjunctiva of host eye tissues, triggering tear production. Both sexes have sponging-type mouthparts that absorb nectar and fluids from eyes, faces and other body orifices. One to five face flies per eye per day can cause serious ocular lesions that mimic the symptoms of bovine pinkeye. Mechanical damage, whether sustained by face fly mouthparts, dust, weed, pollen or excessive sunlight, predisposes the eye for infection and increases epithelial discharges. Fly feeding also prompts animals in pasture and rangeland to exhibit a variety of defensive behaviors, including head throws, tail flicks and bunching together with their heads inward to avoid attacking flies.

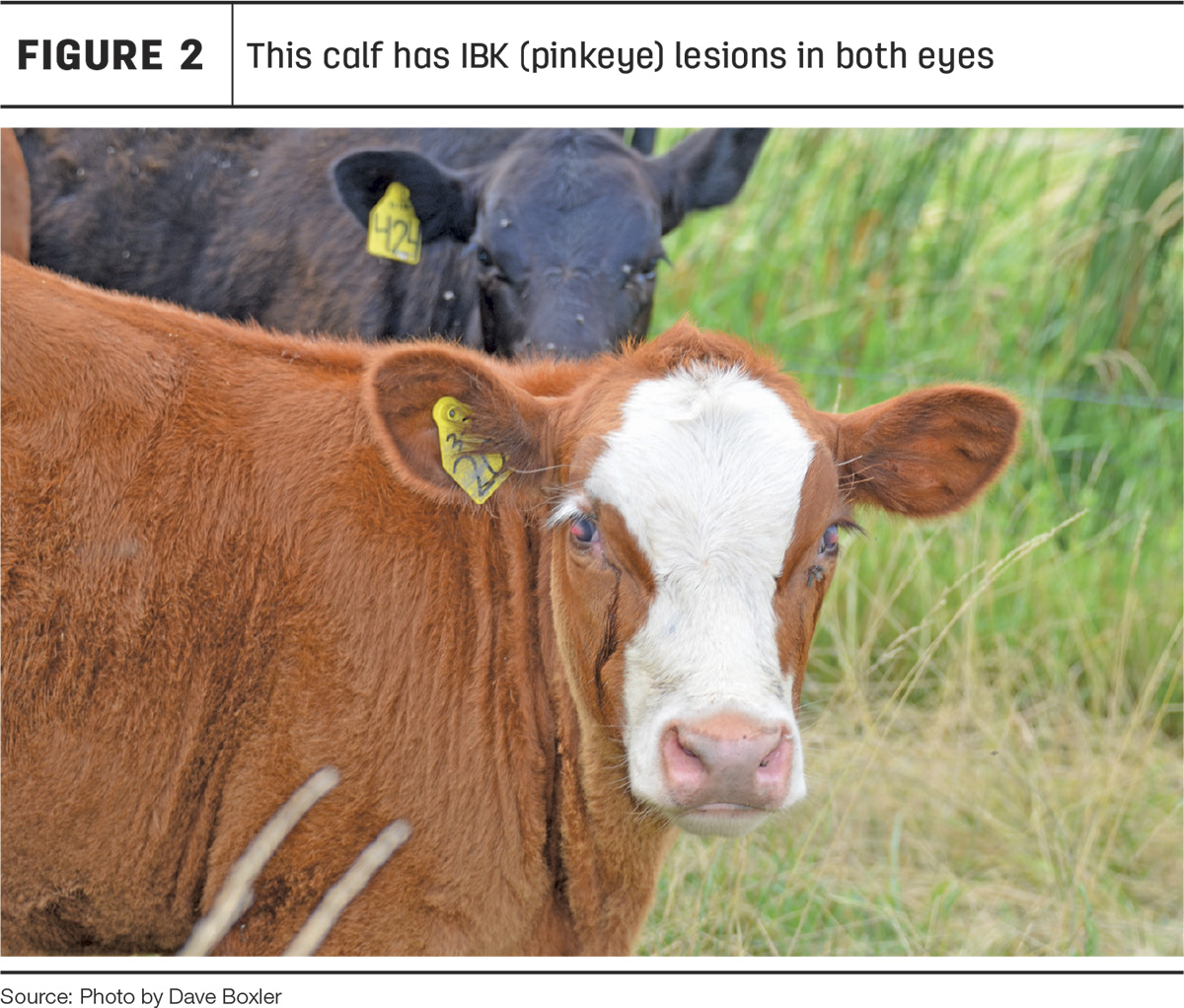

Infectious bovine keratoconjuntivitis (IBK), also known as pinkeye, is a common eye disease of cattle caused by bacteria: Moraxella bovis, M. bovoculi and M. ovis. Clinical signs of IBK are excessive tearing, eye inflammation, conjunctival edema, corneal opacity and ulceration (Figure 2). To monitor for bovine pinkeye, typical signs include excessive tears, excessive blinking, opaqueness, photophobia, lesions and squinting or involuntary eye closure.

Animals with IBK may exhibit weight loss, impaired vision, eye disfigurement and blindness.

Face flies can also transmit thelazia eyeworms, which are nematodes that can infect several different host species and are found on nearly every continent. Clinical signs of infection resemble mild cases of pinkeye, including lacrimal secretions, conjunctivitis, corneal opacity and lesions of the eye and surrounding tissues. Within the U.S., the four thelazia species eyeworms that occur in cattle and horses are exclusively transmitted by the face fly.

Life cycle of face flies

Female face flies lay their eggs in fresh bovine dung pats. Larvae burrow into the moist dung and feed by filtering bacteria, yeast and small organic particles from dung liquids. As the larvae complete their development, they leave the dung pat and burrow into the surrounding soil where they develop into the pupal stage. Males emerge one to two days before females. The complete life cycle can be completed usually in 18 to 20 days depending on temperatures.

The number of face fly generations per year can range from three to four in northern latitudes to as many as 12 in the southern range. In late summer and early fall, as temperatures start to cool and day length falls below 12.5 hours, both sexes aggregate on sunny sides of natural and man-made structures. They will work their way into cracks and crevices where they eventually spend the winter, usually in areas such as attics, lofts and walls of buildings, until temperatures are warm enough to draw them out in spring. In spring, survivors emerge and mate, females search for a host and feed, and eventually deposit eggs in fresh cattle manure. Overwintering flies can survive changing temperatures of 17.6ºF to 46.6ºF for months.

Fly control

Annual losses in face fly control costs and lost animal production were estimated to exceed $52 million in 1967 for U.S. range cattle, which would be approximately $469 million in 2023 dollars. Measuring direct impact of face flies on cattle, the prevention of disease, especially pinkeye, is a strong incentive for livestock producers to manage flies. While face flies can mechanically transmit bacteria that cause pinkeye, the presence of face flies does not imply pathogen transmission, nor does the absence imply no transmission.

Control of the face fly is difficult because it is generally on the face of the animal, an area difficult to treat because it spends little time on the animal. Treatment is generally achieved with self-treatment devices, dust bags, oilers/rubs, insecticide eartags, feed-throughs and air-projected capsules.

Dust bags provide good control if they are used in a forced treatment situation where animals must pass under them to obtain water, feed or mineral. If dust bags are used free-choice, they should be placed in a location frequented by the cattle and in enough numbers to provide access for all the cattle. Recommendations for oilers/rubs are essentially the same as for dust bags. The maximum effect for both delivery systems is in a force-use arrangement.

Insecticide-impregnated eartags provide reasonably good face fly control, especially tags containing a synthetic pyrethroid insecticide. Follow label recommendations regarding the number of tags per animal. Face flies are equally attracted to both adult cattle and calves, so all animals will need to be tagged.

Animal sprays are most frequently applied with a low-pressure sprayer or a hand pump sprayer and will need to be reapplied throughout the fly season. Pour-on products will provide control for a limited time. Follow label directions when applying these products and select a pour-on which permits treatment to the head area.

Feed-throughs, also known as insect growth regulators (IGRs) are insecticides fed through loose minerals, mineral block, lick tub or loose salt. These insecticides pass through the animal and into cattle manure where they kill developing fly larvae but have no activity against adult flies. The active ingredients diflubenzuron and tetrachloroviniphos are labeled for face fly control. When using feed-throughs, it is important to ensure steady consumption, and these control products should be made available to cattle 30 days prior to the start of the fly season.

Air-projected capsules are available in two different modes of action and will need to be reapplied during the fly season. A list of control products and various modes of action are available in the VeterinaryPestX database.

Non-chemical control methods include walk-through traps, sticky traps and conservation of beneficial insects such as predatory dung-inhabiting beetles. Commercial and autogenous IBK vaccines are available to help manage IBK and, if used, should be administered before animals are sent to summer pasture. Please consult with your veterinarian about the use of these vaccines.

If face fly numbers are high, more than one method of treatment may be required to provide satisfactory control. Face flies are strong fliers and can disperse great distances. Neighboring areas with high face fly numbers might be supplying face flies to areas surrounding them, sometimes masking the effect of a fly control product.